Causation: Properties and the Laws of Nature

May 1, 2020 • 13 min read •To be honest, I really struggled with the title. There are quite a few topics covered here, all of them are interconnected somehow, but which one is central? Finally, I came up with the one you see above. This post is about causation, and there are two major views on that. Both of those views stand upon two major topics: properties and the laws of nature. Your stance on those topics, in turn, depends on how you perceive induction.

Categorical and Dispositional properties

Categorical properties

There is an apple in front of me right now. It’s red. This property, “being red”, describes this apple as it really is, not as it could be upon some conditions. This kind of properties is called categorical.

Now consider two billiard balls. They are at the table, lying still. “Being still” is a categorical property. Now imagine that they collide. What would happen? Your experience probably tells you that they would bounce away, which is, most probably, true. But why is it so? If you’re all into categorical properties, you would like to explain this behavior through the way those balls are. Your best bet might be to appeal to the specific way its molecular structure is. Categoricalist naturally prefers descriptive vocabulary instead of prescriptive. For example, categoricalist won’t say that the balls are bouncy. This phrase implies that they need to bounce away when colliding. It implies a necessary causation: if the balls collide, they will bounce away. They simply don’t have other options.

And what if those balls have never collided so far, and never will? Then “being bouncy” does not describe the world as it is. Instead, it describes it as it could be upon specific conditions. In other words, it’s not a categorical property. What is it then?

Dispositional properties

Causation

From the old days, people were preoccupied with different variations of a simple question: “What caused it to be the way it is?”. Like, “Why do I always get sick when I go hunting a mammoth wearing only a tee-shirt in winter?” or “Why do I always get better if I drink hot water and lie in my bed for a couple of days?”. In other words, people have always been interested in causation.

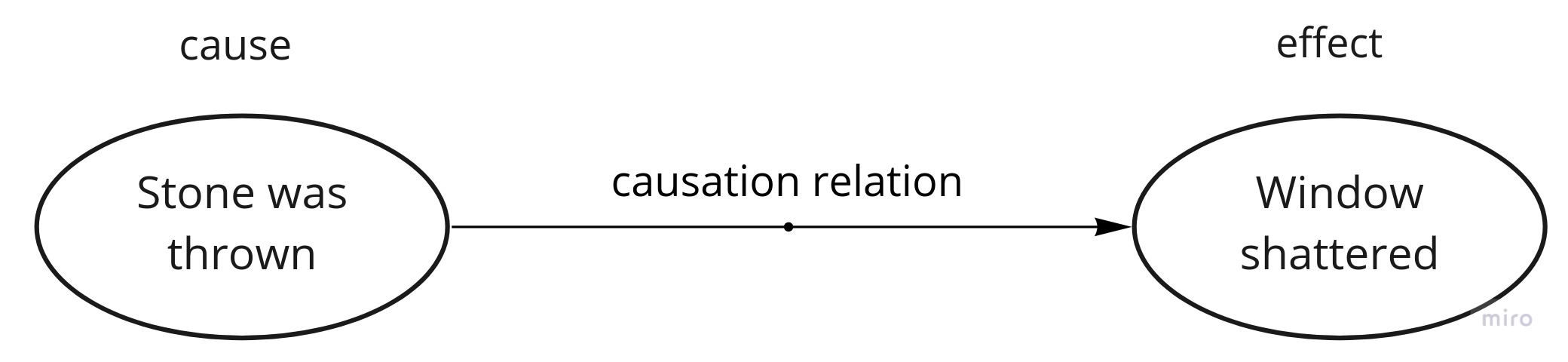

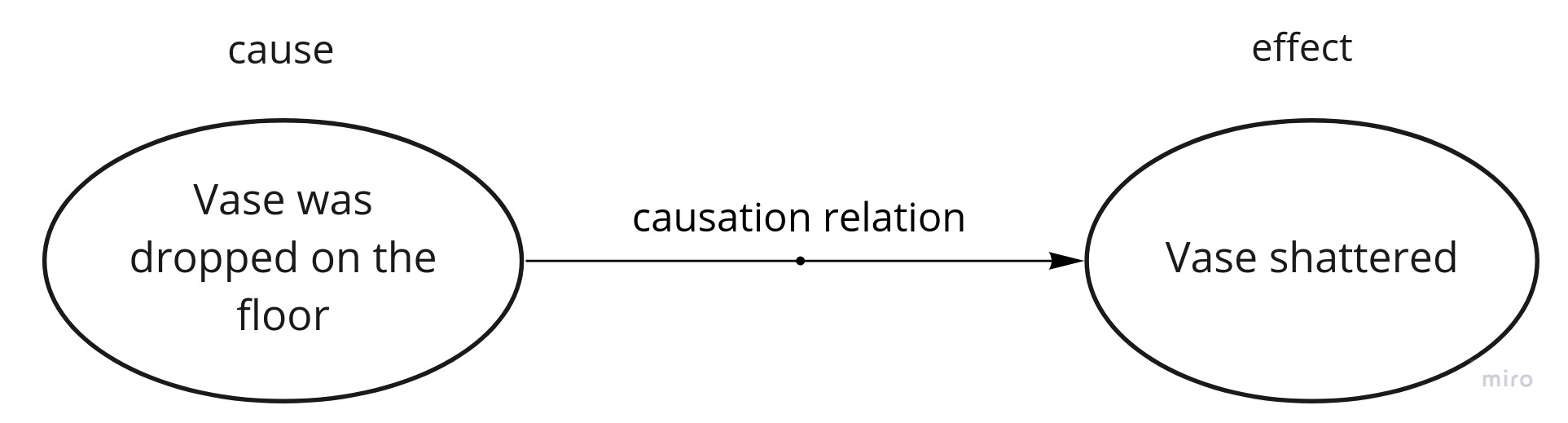

Cause is a change (typically some action or event) sufficient for some event to take place. Throwing a stone at the window is often sufficient for it to get broken. Broken window is an effect caused by throwing a stone. The relation between those two event - ”Stone was thrown” and “Window was broken” - is called a causation relation. It’s a metaphysical way of saying “If I throw the stone at that window, it will break”.

Dispositions

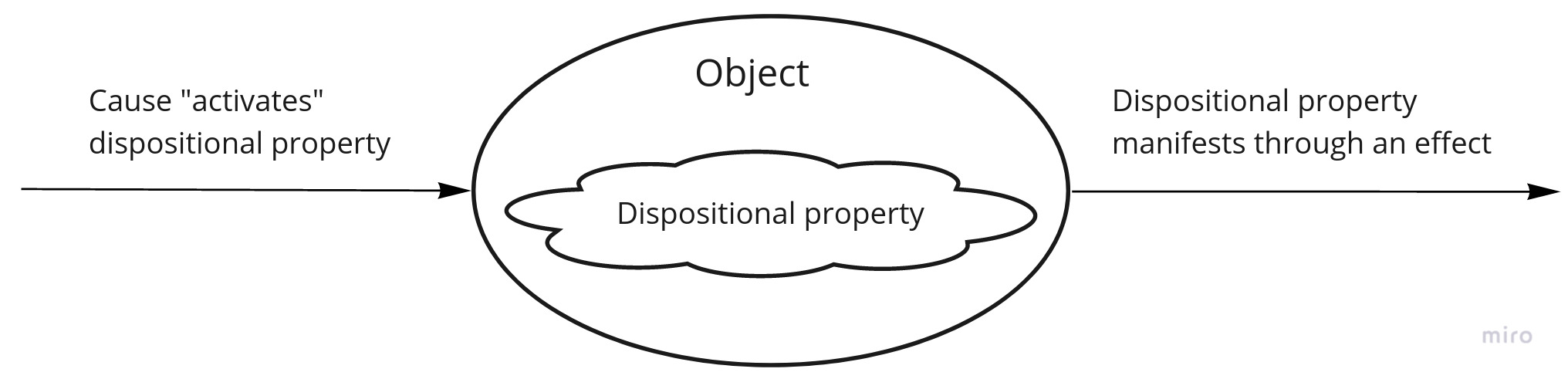

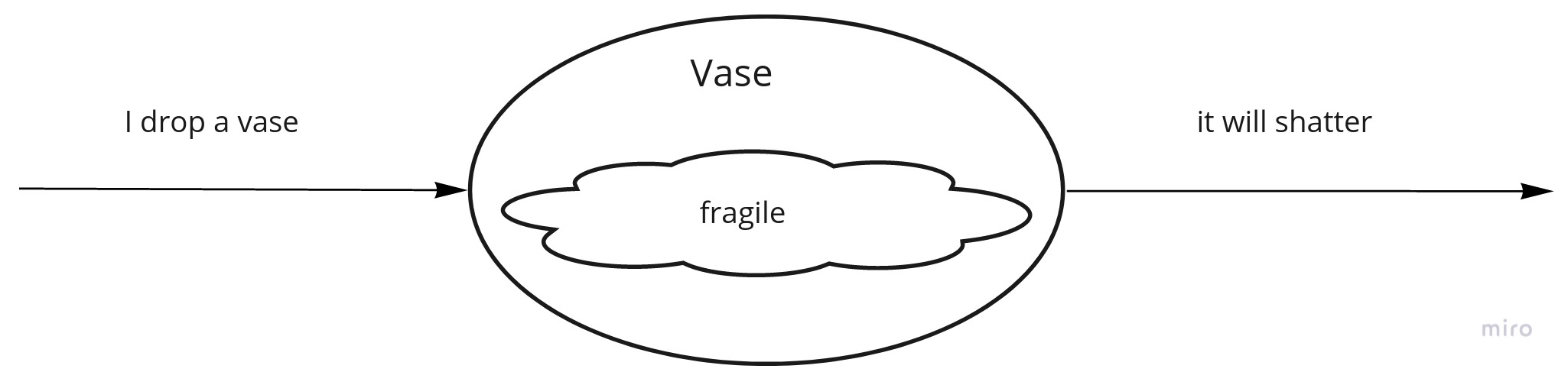

Dispositions are properties describing how something could be. Proposition “this vase is fragile” tells us that under standard conditions, this vase will shatter if it drops on the floor. When dispositional properties are considered, it’s arguably more convenient to view cause as an action:

For example, if I drop a vase, it will shatter:

If I consider a fragility of a vase as a ground for a causal relation, I use an event as a relatum:

Dispositionalists assume that dispositional properties are fundamental. That is, there are no categorical properties that ground them.

Inductive Reasoning and the Uniformity Principle

Let’s start out with an example of inductive reasoning. Suppose that I’ve approached my neighbor’s dog, Rex, a week ago. I wasn’t sure what to expect of him, but luckily, he hasn’t bitten me, and I’ve petted him. So my initial hypothesis was that Rex was friendly. The next day I did the same. And the next day too. Have been doing it for several days in a row, collecting more and more evidence, I strengthened my initial belief about the dog’s temper. I presuppose that the future will resemble the past and the present, a principle called “the Uniformity Principle”, and right now I can infer the following: “The next time I approach Rex I’ll stay safe”. In the same vein, I can make the general claim: “Rex is friendly”.

The dog might have been reacting aggressively all along; then I should have adjusted my beliefs about him accordingly. And that’s the essence of inductive reasoning: new relevant evidence affects my current beliefs, serving either as a testimony or a counter-argument; and this belief is a basis that grounds my considerations about the future.

Inductive argument

The argument about Rex can look like “I’ve been petting that dog for several days in a row, and he hasn’t ever bitten me. Thus, the dog is friendly”. It’s an inductive argument, since the premise - ”I’ve been petting that dog for several days in a row” - doesn’t provide total support for the truth of a conclusion. For example, the dog might have been sick, hence the apathy have been taken for friendliness.

Compare it with a deductive argument:

- Premise 1: if it’s raining now, I’ll take an umbrella.

- Premise 2: it’s raining now.

- Conclusion: I’ll take an umbrella.

Its premises logically entail the truth of the conclusion, which is not the case for an inductive argument.

The problem of induction

Induction is great, we rely on it and often it serves us well. Scientific research, trials - they are all about induction. But here is a kicker: it seems that there is no way to prove that it works.

Let’s consider a simple induction, a typical inductive argument:

Premise: All observed instances of A have been B.

Conclusion: The next instance of A will be B.

Let’s call this inductive argument I.

Here’s a simplified version of an argument that David Hume, a Scottish philosopher, laid out in “A Treatise of Human Nature”:

Premise 1: there are only two kinds of arguments: inductive and deductive.

Premise 2: inductive argument I presupposes the Uniformity Principle.

Premise 3: a deductive argument has a conclusion which is necessarily true - by definition. Its denial is a contradiction.

Premise 4: the negation of the Uniformity Principle is not a contradiction - we can’t know for sure what the future brings.

Conclusion 1: there is no deductive argument for the Uniformity Principle (from Premise 3 and Premise 4)

Conclusion 2: since there is no deductive argument for the Uniformity Principle (Conclusion 1), any argument for the Uniformity Principle, if present at all, can be only inductive (Premise 1).

Conclusion 3: since any inductive argument presupposes the Uniformity Principle (Premise 2), any argument (Conclusion 2) for it presupposes the Uniformity Principle.

Premise 5: an argument for a principle can’t presuppose the same principle.

Conclusion 4: there is no argument for the Uniformity Principle.

Conclusion 5: since there is no argument for the Uniformity Principle, we can’t use it for justification of any inference that presupposes the Uniformity Principle.

Conclusion 6: inductive inference I is not justified.

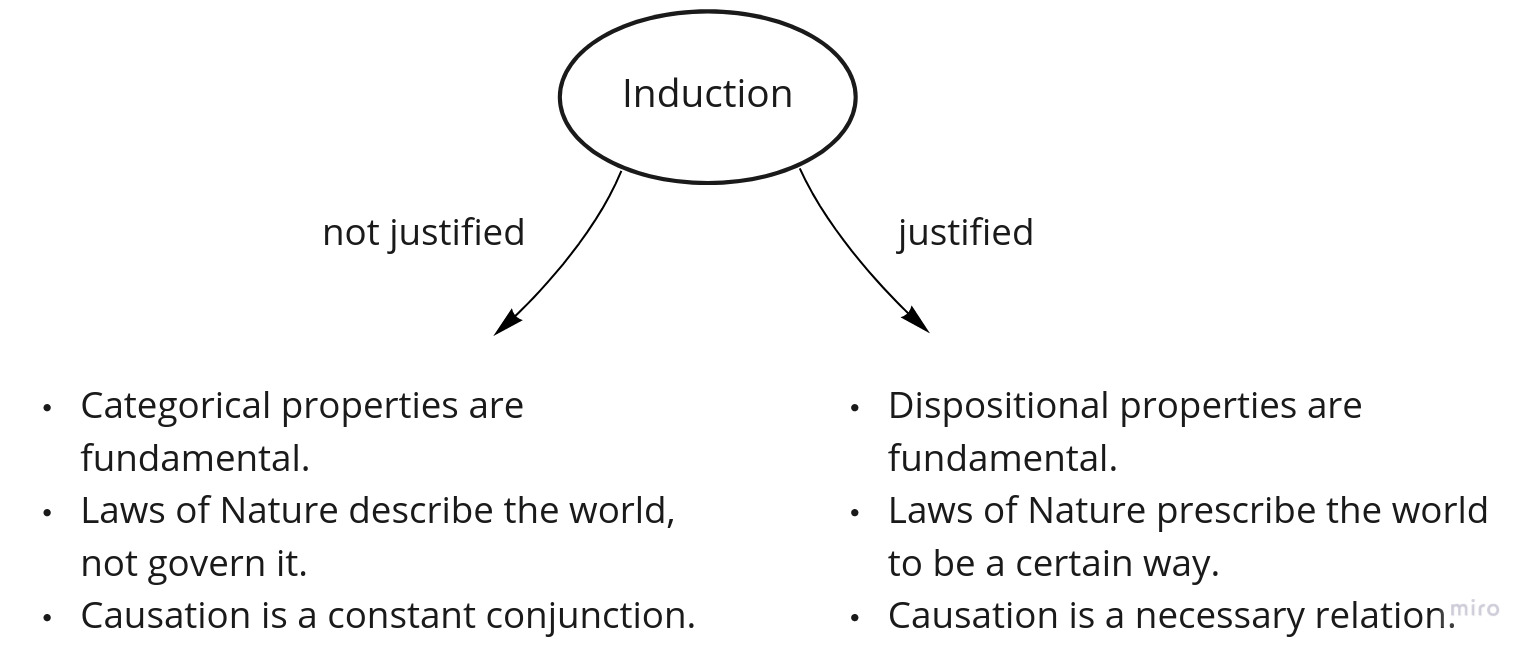

There are a lot of attempts to solve this problem, and each of them has its pros and cons. The problem of induction is a primary cornerstone dividing people in their views on causation.

Abstraction process is guided by inductive reasoning

Abstraction is a process when general ideas are crystallized from specific examples. The result of this process, an abstraction, is that general idea, a concept, having specific essential properties, which denotes all the concrete examples.

The process of forming abstractions – not discovering the existing abstractions, but forming new ones – is inductive indeed, by definition. Let’s say that some man has picked up an apple about a hundred thousand years ago, for the first time in human history. Probably, it was red and sweet, having a particular form and size. Most probably, that man came up with a name that referred that apple. After that, he told his friends about his finding. They got the idea, and since then they started to pick up particular red objects which they called apples, too. After that, someone’s stumbled upon with some new stuff: a yellow object, with a shape and size similar to what he knew as an “apple”. At this point, there is one question to be answered and one decision must be made. The question goes like “What does it mean for something to be an apple?”, or, put slightly different, “What essential properties make up an apple?”. After that, we must decide whether we consider an “apple” abstraction to be already fixed, or still subject to change? Can some new evidence change our definition of that abstraction? In other words, are we still in the process of forming an abstraction? If yes, then we can reconsider our understanding of what it means to be an apple. In that particular case, a man who’s encountered a new sort of apples, probably decided that red color was not essential. Yellow objects have a similar taste, size and form, hence deserve to be called apples either.

This whole process is inherently inductive, with a series of scientific method loops. First, a hypothesis was formed: apples are red and sweet and have a particular form and size. After that, new evidence was encountered: something yellow, which is very much alike with what we know as an “apple”. And, finally, an initial hypothesis was revised. At some point, when enough data was collected, we can decide to fix an abstraction. That is, no new evidence can change the properties essential to that abstraction. After that, the new evidence can be checked against that abstraction, to find out whether an object under test belongs to it or not. But this process is deductive, not inductive.

An example of forming abstractions at scale, driven by our abstract thinking ability, is the way a language evolved. First of all, all the nouns of all languages in the World serve the single purpose: they reflect some general idea, that is, an abstraction. Now, take my initial example with apples. Today, if you look at two apples, it’s not a problem to say that both of them are apples. In a blink of an eye, you observe their properties, extract the ones which make those two similar, and conclude, based on the resulting property set, that the underlying concept is an “apple”. That’s an example of abstract thinking, which we are now way better in, comparing to a hundred thousand years ago. Back then, due to the way our brain worked, it was a way more tedious task. And that’s the reason why the first language on Earth, whatever it was, had a very limited amount of words, at least nouns. Just to reiterate: nouns represent a general idea, and a general idea is reached through the process of abstraction which we were not particularly good at. So, there were only words for abstractions that we humans have managed to come up with, and that number was not impressive. Naturally, those abstractions were extremely coarse-grained. Further human evolution in abstract thinking area went hand in hand with the evolutions of languages: the better we became in abstract thinking, the richer our vocabulary grew.

Laws of Nature

Laws of Science vs Laws of Nature

There are a lot of laws discovered by scientists. Some of them are seemingly simple, but not so accurate, or limited to a narrow set of cases. Others are more complicated, but work in a wider spectrum of cases. Generally, a law of science is an approximation good enough for solving specific problems. Take Hooke’s law. The formula in its simplest linear form works either for ideal springs or for very stiff materials like glass. A general form of Hooke’s law looks way more complex, but it’s more universal: it works for more materials.

Laws of Nature are approximations with the best combination of simplicity, accuracy and generality. We consider such laws to be the most fundamental ones, which ground most of other laws. Wikipedia has some good examples of scientific laws which can claim to be the Laws of Nature.

Two principal views of the Laws of Nature

In Regularity Theory, Laws of Nature are just descriptions of repetitive patterns of the world. In this view, nothing must be the way it is. It just is. It’s not necessary for the Sun to rise again tomorrow morning, because the Uniformity Principle is not justified and inductive reasoning doesn’t work. Anyway, if the Sun does rise - great, our current understanding of the World will not change. If it doesn’t, the Laws of Nature will have to be adjusted accordingly.

In Necessitarianism, on the other hand, the Laws of Nature govern the World, and it obeys. Those laws can’t fail. There is no way for the World to escape those laws. Another name for this hopeless relation is “physical necessity”.

There are two different kinds of this necessity. From the Nomists point of view, this relation is external, that is, it’s independent of objects’ properties; in other words, it’s not fixed by its properties. For example, the fact that I’m ten meters away from some tree is not defined by intrinsic properties of mine. From this perspective, an electron repels other electrons because there is an external guidance that makes them act the certain way. On the contrary, from the Powerist view, an electron repels other electrons because of an intrinsic dispositional property, namely “repelling other electrons”. Thus, in Powerism, the Laws of Nature are grounded in dispositional properties.

At this point, you might notice that two natural groupings are formed, depending on your take on induction: whether it’s justified, or not.

If you feel like induction is fine, chances are you prefer dispositional properties which promise that the world will be a certain way upon specific conditions, and Laws of Nature are those promises taking a form of prescriptions. As a result, causation takes the form of a necessary relation: events are bound together, resulting into a specific outcome with known probability.

If you feel like induction is fine, chances are you prefer dispositional properties which promise that the world will be a certain way upon specific conditions, and Laws of Nature are those promises taking a form of prescriptions. As a result, causation takes the form of a necessary relation: events are bound together, resulting into a specific outcome with known probability.

If you’re uncomfortable with relying on induction, then most probably you’d prefer categorical properties which describe the world as it currently is. Laws of Nature are those descriptions, and no promises about the future possible states are given. As a result, causation takes the form of constant conjunction: (highly) likely, but not necessary pairs of events. Again, no promises about the actual probability: it predicts relying on induction, and you don’t trust it.

Neo-Humeism

Neo-Humeism is a combination of Regularity theory and Categoricalism. In other words, Neo-Humean worldview is categorical properties spread over the spacetime, mutating in unpredictable ways. The world is not governed by anything, or anyone. Laws of Nature just describe the world as it is, and there is no chance that we can ever discover them. Even though some causal relations hold for ages, nothing makes them do so in the future, because the Uniformity Principle is not justified. For example, two billiard balls don’t need to bounce away when colliding, though, most probably, they will. The fact that they have been doing this all along is described with a special term “constant conjunction”, which can be read like “there is no physical necessity in balls bouncing away after collision, though it happens time and again”.

Its main advantage is ontological simplicity. There are no necessary causal relations like in Necessitarianism.

The main objection stems from Scientific Realism. It’s the view that we do possess some knowledge about Nature and its laws. That knowledge doesn’t depend on our specific scientific practices or our choice of what we call a good theory; it is imperative: the world must be the specific way.

Induction rejection raises the second objection. It’s been a huge part of the scientific method - empiricism, to be precise. Given an apparent success of science, how comes that inductive reasoning is not trustworthy?

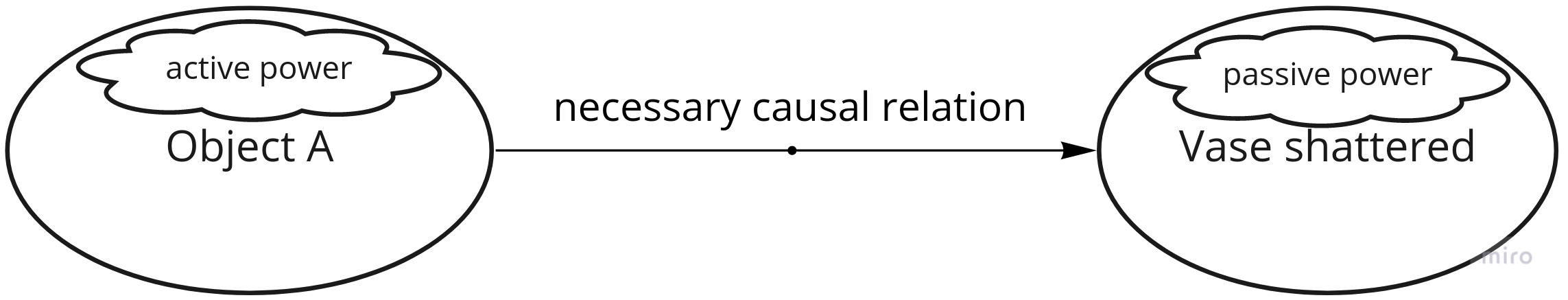

Powerism

Powerism is a combination of two views: Dispositionalism, which postulates that dispositional properties are fundamental, and Necessitarianism, which says that the Laws of Nature don’t just describe the World, but govern it. Moreover, they can’t fail in doing so. In other words, those Laws are necessary.

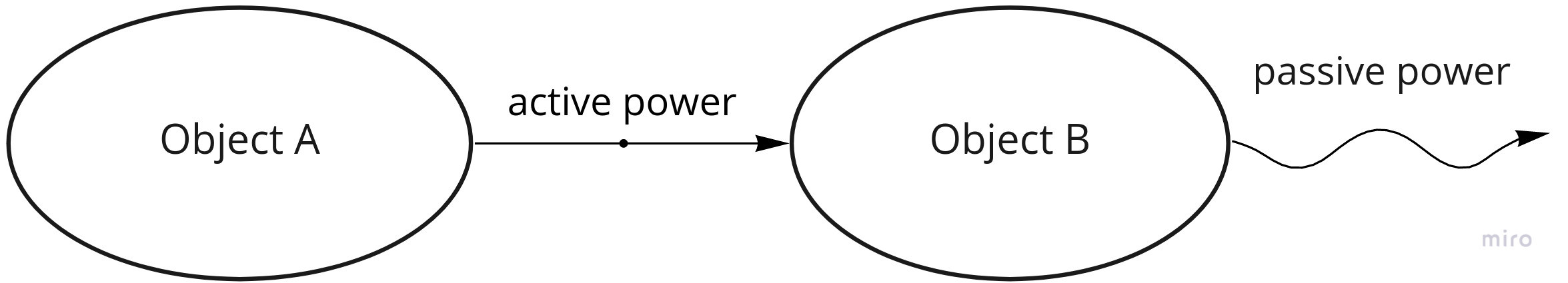

Powerist folks use a special lingo. Active power is a cause. Some object possesses an active power when it’s able to induce a certain kind of change in other things. Passive power is an effect. An object possesses a passive power when it’s disposed to undergo a specific change under specific circumstances.

Powers bundled together often constitute some natural and ubiquitous formations. For example, if something repels electrons and attracts protons, then it’s probably an electron. If something emerges in the presence of oxygen and a spark, can heat other things and dies down in the absence of oxygen, it’s probably fire. So if you accept powers as such, you can employ them to discover natural kinds.

Advantages

First, Powerism goes in accordance with experimental science. Instead of simply watching categorical properties and their constant conjunctions, Powerists build knowledge. They rely on the scientific method: pose a hypothesis, carry out series of experiments, analyze results and draw a conclusion which either supports or weakens previous belief. That’s the way the Laws of Nature emerge.

Second, Powerists can explain a causation direction with causal relation, which is grounded in fundamental dispositional properties. Fire has an active power to heat anything; water has a passive power to boil when heated. Hence, when both are put together, fire is a cause of heating water. Water boiling is an effect. Besides, because of Powerists’ view of the Laws of Nature, this directed cause-effect relation is necessary and must be exactly the way it is. It can’t cease to exist or change its direction.

Objection

We can say that some events are caused by absences. For example, an absence of water causes a plant to die. The same way we can say that some events cause the absence of something. It’s a typical case of prevention. For example, vaccination causes the absence of - in other words, prevents - a disease.

The problem here is that Powerists have to attribute powers to absences. But absences, by definition, don’t exist, and hence they can’t be attributed any powers. Hence, they can’t form causal connections.

Powerists can either deny negative causation phenomena or say that it’s totally fine to attribute powers to absences, but the general view is that negative causation can’t be eliminated entirely. That is the cost of Powerism.

Conclusion

I’ve outlined two main perspectives on the nature of causation: Powerism and Neo-Humeism. The view on properties and the Laws of Nature is what differentiates them; both differences are grounded in one’s position on the problem of induction.

Just to reiterate, Powerism is about causal relations grounded in dispositional properties, which are necessary because the Laws of Nature say it can’t be otherwise. Neo-Humean worldview is categorical properties spread over the spacetime, where causation takes a weaker form known as “constant conjunction”, because the Laws of Nature don’t govern the world, but just describe it, ready to change.

Further reading

It’s not an exaggeration to say that this topic is huge.

If you’re interested in a thorough analysis of dispositions, take a look at this entry.

If you want to take a really close look at the metaphysical structure of causation, here is a good source. Diving even deeper, here is a comprehensive description of causal relata – events.

Ability, intention and action are all very close to power, though they’re human-centric and belong to the philosophy of mind area.

Wikipedia has a nice introduction in an inductive reasoning. Differences between inductive and deductive arguments, along with descriptions of each one are outlined here.

A deep dive into the problem of induction and its major possible solutions can be found here.

One of the most widely-known mathematical applications of induction is Bayes’ theorem, which, in turn, is the foundation of Bayesian statistics and Bayesian inference.

You can find deep investigation of the Laws of Nature here and here. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, as usual, explains thing in simpler terms comparing to Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Great introduction into the scientific method can be found on Wikipedia.

Last but not least, check out chapter three of Metaphysics: The Fundamentals.