Objects

October 1, 2020 • 20 min read •I’ll start this post with a common and plausible observation: there are things, and there are ways those things are. If you’ve read my previous post on properties this might sound familiar already. Those ways are properties that things possess. Here, I’ll delve deeper into the nature of things, or objects. What are they? What do they consist of? What is the relationship between objects and their properties?

What objects are

To better understand some concept, it’s good to contrast it with something already familiar. Hopefully, you’re already familiar with the concept of properties, so let’s compare objects with it. I don’t intend to give a holistic, cohesive, and non-contradictory metaphysical distinction account here. It’s just a set of assumptions, some of which might seem plausible, and some of which might not. And some of them very well can (and, actually, do) contradict one another.

We can start with something as simple as the fact that there is a red apple in front of me.

Objects are subjects, properties are predicates

One of the most obvious distinctions between objects and properties is that in any given atomic proposition, the former is represented as a subject and the latter as a predicate. Indeed, look at the following sentence: “Apple is red”. Intuitively, apples are objects, and being red is a property. At the same time, “apple” is a subject, and “is red” is a predicate. And this is a repetitive pattern.

Note that this assumption doesn’t presuppose that objects are material. Look at “One is the loneliest number”, or “Monday is blue”. None of the mathematical objects or days of weeks are material, though they can be subjects in sentences. But none of the properties can say the same. Can you imagine “is red” as a subject after all?

Objects are in spacetime, properties are not

I can definitely say that an apple is in front of me. But is redness in front of me either? I’m pretty much sure that an apple is here and now. Can I say the same of redness? If so, where was it last Tuesday? Or, here is another good question. Say, this apple is a very special apple having a unique shade of red. Now I’ll eat it. Where is that particular shade of red? There is nothing in the World having this color. Is it gone? Or has it ever existed?

The view that redness exists, but as some transcendent entity that is out of spacetime, is called Platonism. And such kind of entities is called a Universal. But there are other accounts, implying that redness is here in front of me, namely Immanent Realism and Trope theories.

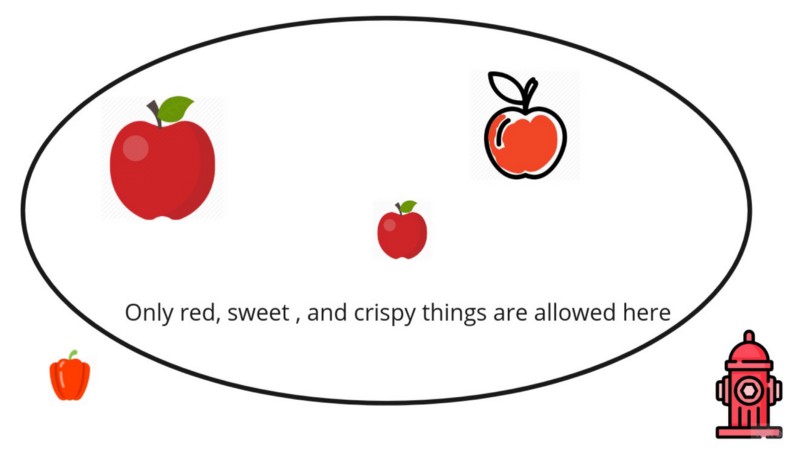

Objects are singly-located, properties are not

Whatever view you take, it seems plausible that while an apple occupies a single specific space region, redness doesn’t. It’s in my apple, in your apple, in a firetruck, in a hydrant. In other words, it’s multiply-located.

You might think of the nineteenth-century British Empire. It had several parts scattered around the world, so it might sound plausible that it’s multiply located. But all those parts belong to the single British Empire, which has definite size and location. British Empire as a whole is singly located. Talking about redness, all those different regions of red are not metaphysical parts of the single redness: it doesn’t get bigger with each new red apple grown, it doesn’t get smaller with each red apple eaten. If you believe in Universals, all those red apples just instantiate the single transcendent RED-ness, they are in no way a part of it. If you favor the Trope Theory, those apples just have red-tropes, and they primitively resemble each other. Once again, there is no single red-entity which they all are part of.

Objects are perceptible with our five senses, properties are not

An apple is tangible, I can touch it. But can I touch redness? I can taste an apple, but can I taste its sweetness? Once again, it depends on your take on properties, actually. For Platonists, properties are Universals and you definitely can’t perceive them. For some Trope Theorists, it’s otherwise: for them, objects are nothing but bundles of tropes. So, according to their views, you see an apple’s redness and taste its sweetness. But, nevertheless, those properties can’t exist individually, that is, separate from an object.

What objects can do

Since an object as a category is a quite high-level one, its roles that I’ll list here are high-level either. As well as the previous chapter, the assumptions outlined in this section do not form an exhaustive, cohesive, and non-contradictory account.

Objects can be quantified over

It seems that we can use quantifiers like all, some, many, etc with objects, but not with properties. We can say “All Mondays are blue”, or “Some apples are red”, or “There are five basic universally accepted tastes: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and savoriness”. Thus, Monday, an apple, and sweetness - all can be considered as objects.

Can we say something along those lines with “are blue” or “is red”? It seems that we can’t.

Objects can be thought of

It seems that at least some of our desires, beliefs, thoughts, and other mental entities are about objects. “I hate Mondays” are about Mondays, and about me. I can conjure up both Monday and me. “One is the loneliest number” is about number one. I can think of it either. “Apples are sweet” is about apples, and it’s so easy to think of apples. At the same time, I can’t think of “is red” or “is hated”. Can you?

They serve as objects of reference

We can make the following observations. “The first day of a week” refers to Monday. “The lowest possible temperature” refers to −459.67 °F. “The least common denominator of 1/5, 1/6, and 1/15” refers to 30. “An apple on a table” refers to an apple on a table.

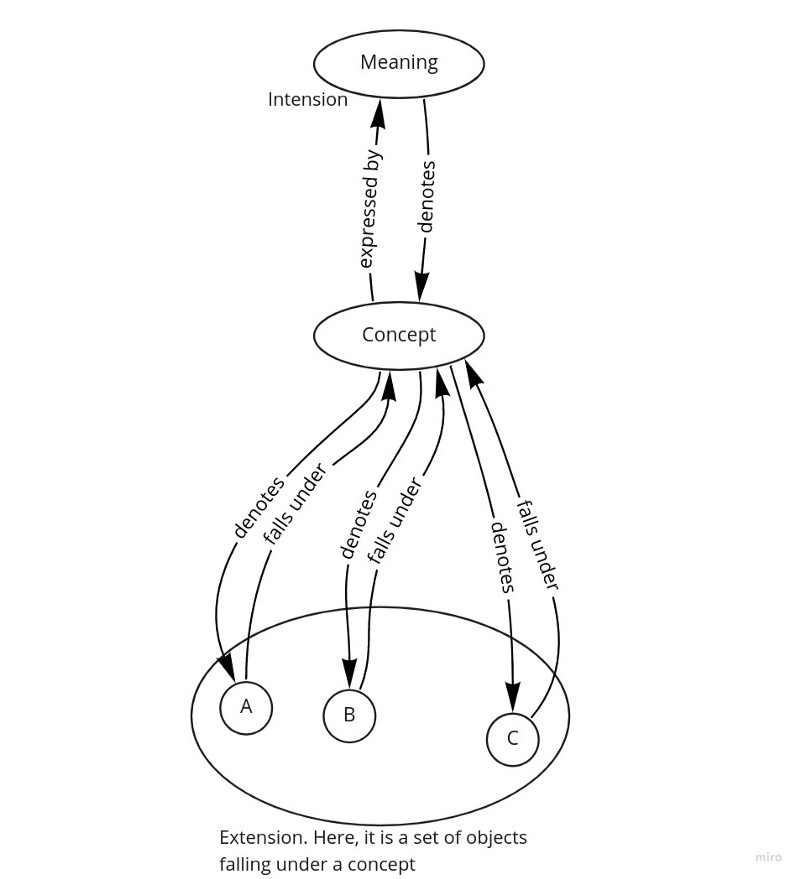

Now take a look at “is blue”, “is cold”, and “is even”. From the previous post on properties, I can say that those predicates refer to their corresponding properties. That’s the difference with the former set of linguistic constructs. They can be viewed in two ways. On the one hand, they are connotations, or intensions, which can act like definitions from a dictionary. They define, and, hence, refer to, the corresponding concepts. And those concepts refer to specific objects.

On the other hand, they are like Fregean senses that express corresponding names, or singular terms, which in turn refer to specific objects.

Those objects of reference can be material and can be not.

To wrap it all up, objects can serve as referents - again, which I can think of and quantify over.

Objects’ internals

Take a deep breath, that’s the longest part. First, we’ll take a look at the most influential views on objects in Ancient and Early Modern metaphysics, and then give an overview of Contemporary ontologies.

A brief history of objects

Aristotle: objects are a combination of Form and Matter

For about two thousand years, right until the Early Modern period, Aristotle’s Hylomorphism was the prevailing idea of an object’s nature. Basically, it’s the concept that objects are a combination of Form and Matter. Matter, according to Aristotle, is what objects are made of, and Form is a kind of thing an object is. Put in other words, it’s a collection of properties that are essential for that object’s kind.

For example, The Thinker is made of bronze, which is its Matter, and it is a (belongs to the kind of) sculpture, which is, consequently, its Form. In spite of the fact that it represents a human being, it is not a human being, since it lacks some properties that are essential for humans. For example, sculpture lacks any cognitive abilities. Hence, its Form is not a human being, but a sculpture.

Matter itself can be decomposed further on Form and Matter. Down to the bottom of this hierarchy, we reach electrons, protons, and neutrons; they too have their Matter and Form. But Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with this Turtles-all-the-way-down regress. He believed that there is a finite level where Matter can’t be decomposed any further. Aristotle called such kind of unintelligent thing, free of any properties, a Prime Matter.

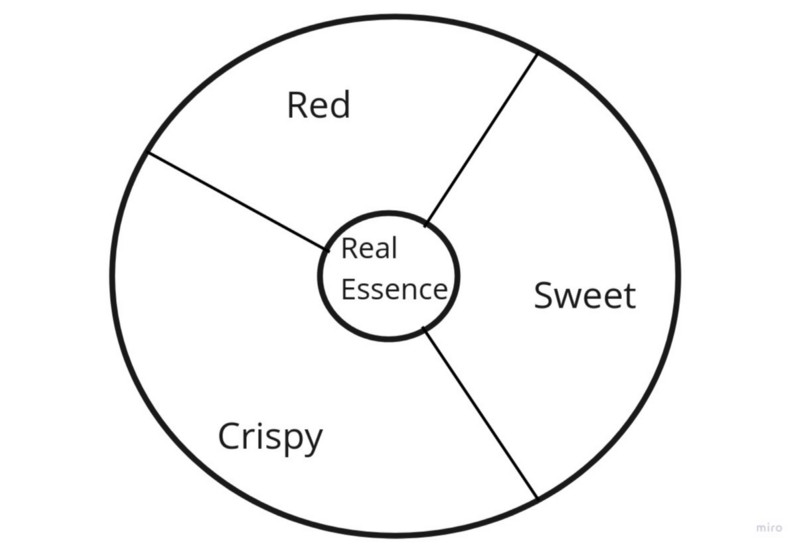

John Locke: objects have a Real Essence and a Nominal Essence

In the 17th century, John Locke took over. He introduced two concepts: Real Essence and Nominal Essence. In his view, all objects are constituted of those two.

Real Essence is an unknown atomic structure. By atomic, it doesn’t imply only what we now know as atoms. It implies tiny particles that are by definition unknowable to humans; thus, the word “atom” is used in a metaphysical, not a physical, sense. After all, right now we know that atoms themselves are constituted of further entities, and those ones are, in turn, either. But we still don’t know for sure what is that fundamental something that everything is made of. So, according to Locke, that fundamental matter is a Real Essence.

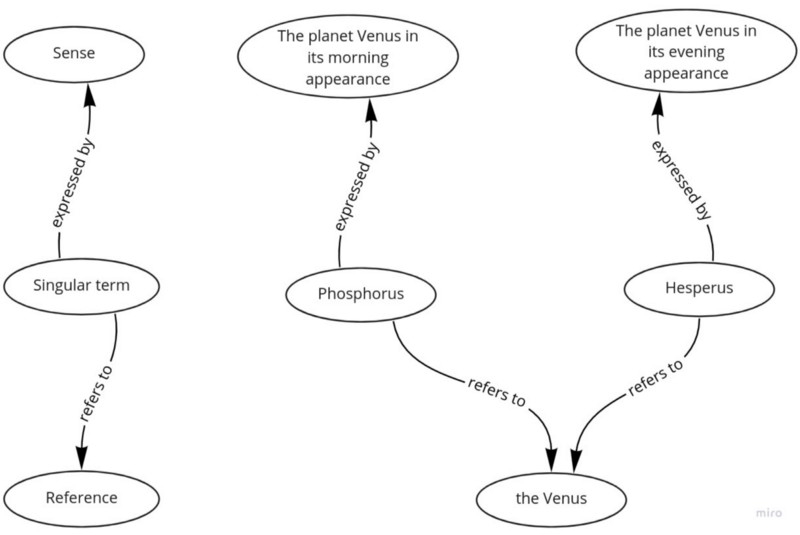

The set of observable properties forms the Nominal Essence. This set is a general idea, a concept we can think of when we see an object possessing the specific set of properties. Some things share those properties, hence they fall under the corresponding concept; others don’t. So Nominal Essence, at the very least, can serve as the basis for objects’ loose categorization, which doesn’t purport the discovery of genuine kinds.

For example, consider some object having the following properties: it’s sweet, red, and crispy. We can think of an apple because the “apple” concept includes those observable properties. As a short sidestep, that’s how it came true. First, when people observed something which was red, sweet, and crispy, they needed a single word to refer to the concept formed by the set of all the things sharing those properties. That’s, roughly, how the “apple” word, and pretty much any other word, emerged. And after the concept was formed, when it’s solid and ubiquitous, it serves as a boundary, including all apples and excluding all non-apples. The same mechanism is true for any other word, of course.

Following this description, Real Essence doesn’t seem to differ much from Aristotle’s Prime Matter. But Aristotle implied that Prime Matter is unintelligent, while Locke’s successors believed otherwise, that it is the underlying cause of all object’s perceptible properties. For instance, Hilary Putnam stated that a Nominal Essence supervenes on a Real Essence. In other words, Real Essence properties are the most fundamental ones, and they form a basis of Nominal Essence properties.

In other words, Real Essence is the motivational and evolutionary force behind observable properties. Thought this way, Nominal Essence can serve as a basis for the discovery of genuinely natural kinds. That discovery is not guided by a human interest in any particular moment of time. As a result, the kinds we’ve uncovered are those that are carved by the very Nature.

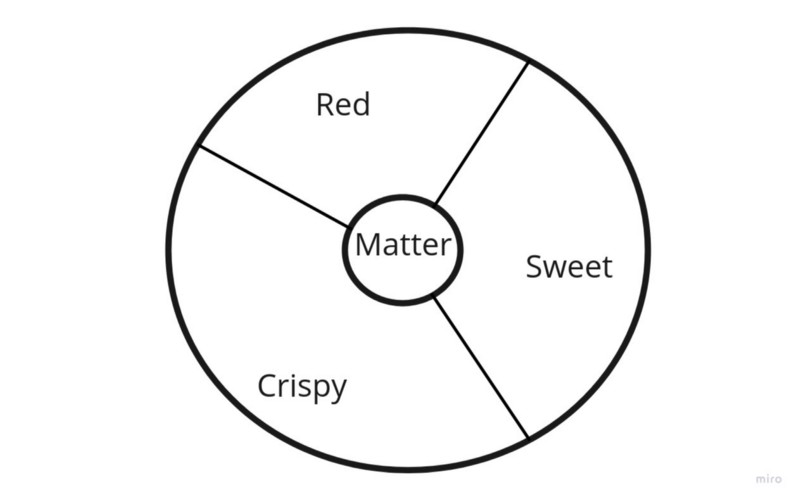

Contemporary Ontologies

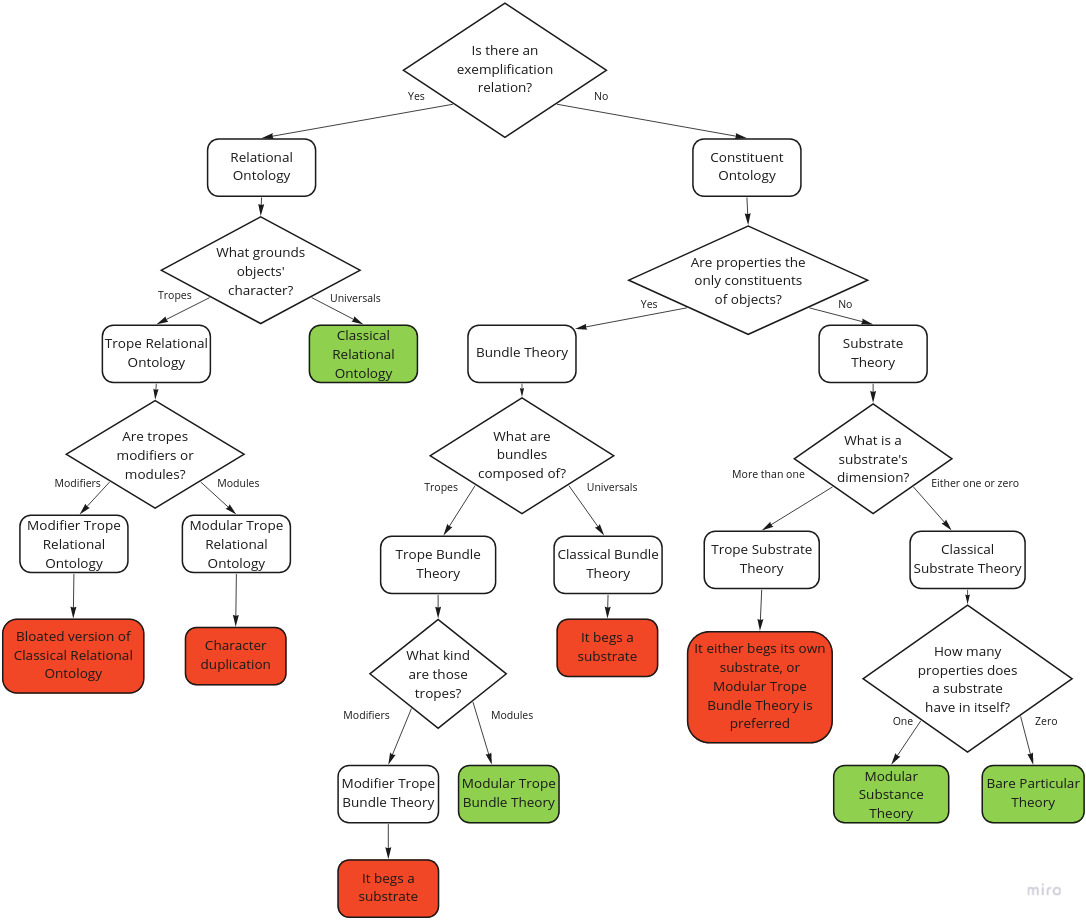

There are two primary views on how objects relate to properties. The first one is that properties are parts of objects. That means that objects and properties are all there is, and there are just those two fundamental entities. Put in other words, objects are constituted (at least partly) of properties; hence the name of this view, Constituent Ontology. The second view extends the first one by adding a fundamental exemplification relation. It means that properties do not constitute objects; instead, objects possess them in virtue of exemplification relation. As you might have already guessed, this view is called Relational Ontology.

Before delving deeper into those views, let’s talk about tropes again. I’ve already written about them in my post on properties to some extent, but here I’ll take a bit broader perspective.

Tropes

There is a major question that divides Trope Theory into two camps: do tropes have a character?

In a view that answers positively, tropes are called modular. They are single-charactered objects. But this character is not what a trope has; it’s what a trope is. Put in another way, a trope is a unit of some property. It doesn’t exemplify that property, doesn’t possess it in any way. It is a property. So tropes are a bit of both property and object: they characterize objects and constitute them. But if it is an object, can you touch it? Actually, no. Tropes are abstract objects in the sense that they are partial, incomplete. You can’t see them scattered at the table. They are ordinary objects, yes - but they can only be constituents of other objects. And those other objects, in turn, can be scattered at the table.

If you consider tropes as lacking a character, they are modifier tropes, because they somewhat modify the perception of an object, providing it with character. They are explanatorily identical to Universals.

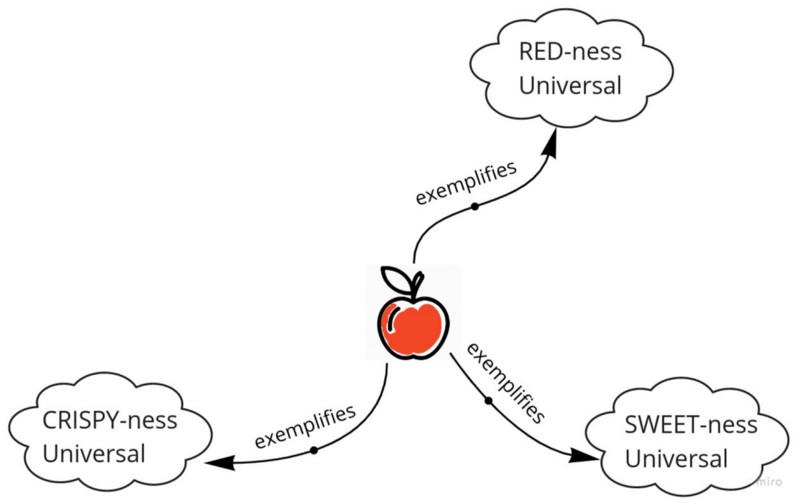

Relational ontology

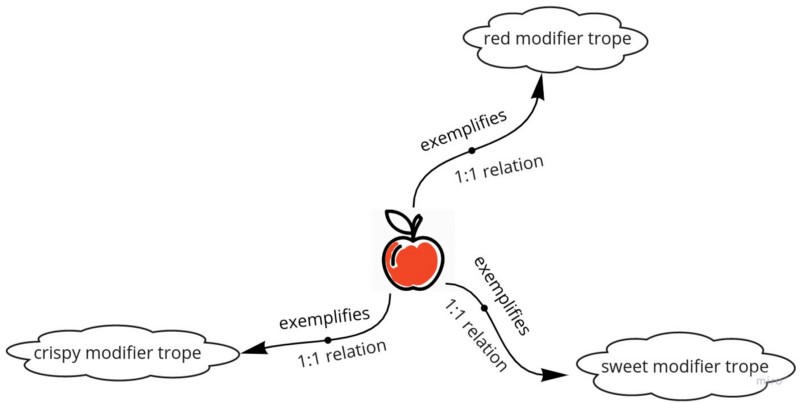

In this view, objects have no metaphysical parts. There are three distinct fundamental concepts: object, or substance, property, and exemplification (instantiation) relation.

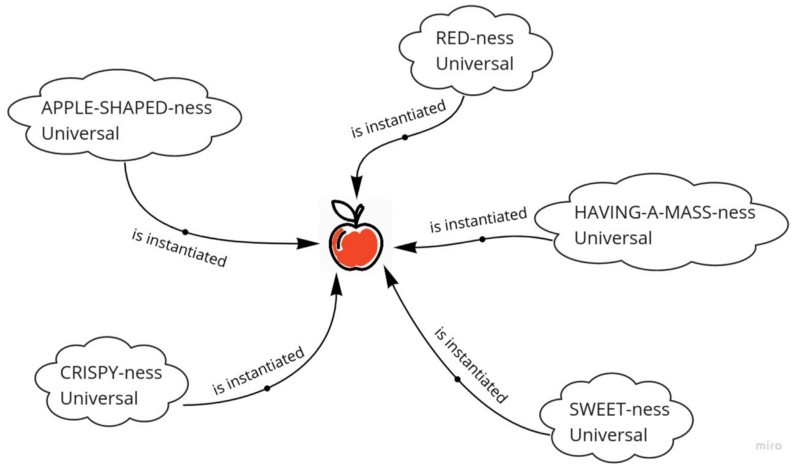

The further account of this view depends on whether you take a Realist or Nominalist view. When it’s combined with Realism, the resulting view is usually referred to as Classical Relational Realism. Short reminder: properties in Realism are Universals, so the whole picture is such that objects possess properties in virtue of instantiating Universals.

There is a specific mental image I conjure up when I hear that, say, an apple instantiates a RED-ness Universal. I imagine that apple is connected via a hose to a huge barrel of red paint. A hose serves as an instantiation relation, and a barrel is a RED-ness Universal. So, as a result, an apple needs both a relation and a Universal to be red.

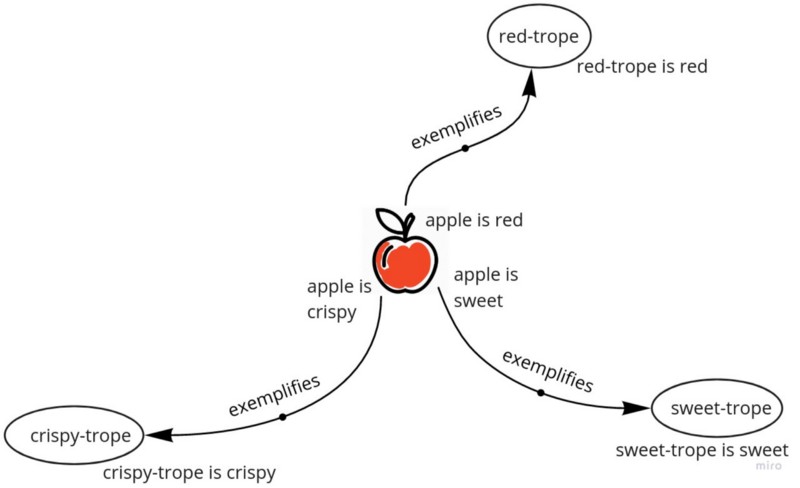

If you are a Nominalism adherent, then most probably you endorse Trope Theory, hence your view is called Trope Relational Ontology.

Since there are two kinds of tropes, there are two kinds of any theory involving tropes either. Trope Relational Ontology is no exception, there are modular and modifier flavours. Modular one is problematic though. In this view, both tropes and a substance have character.

For instance, both apple and red-trope are red. Such duplication is metaphysically unpalatable; it results in vagueness and uncertainty. Moreover, it’s not completely clear how objects, even incomplete ones such as modular tropes, can be instantiated.

Modifier Trope Relational Ontology lacks that drawback: modifier tropes have no character whatsoever. Their sole purpose is to grant character to other objects, which makes them similar to Universals. But how come that modifier tropes are exemplified by a single object?

We can say that a specific modifier trope has a specific spatiotemporal location, exactly the one that the corresponding object has. But in this case, this trope possesses a character, namely, specific location, size, and shape. In this case, such tropes can’t be modifier ones. Moreover, they can’t be tropes, because their character is not single-dimensional. Facing the problems they can’t explain, metaphysicians can take the last resort: claiming something as a brute fact. In our case, they can say that modifier tropes are instantiated by a single object primitively. But this is just a less parsimonious version of Realism, where Universals are instantiated by numerous objects. So Occam’s Razor tells us that Classical Realist Ontology is more preferable. But it doesn’t provide much insight into what it is to be an object. OK, there are objects that instantiate properties. We can perceive objects only as a whole, that is, with all their properties instantiated. But what are objects in isolation? Do they consist of anything? Do they have any properties of their own, or are they “bare”?

That kind of question is answered in Constituent Ontology. And if you’re loyal to tropes, you may find it even more attractive.

Constituent ontology

There are two distinct metaphysical entities in this view: properties and objects. But if there are no relations, how are those two connected? The answer is that objects are constituted of properties. That is, we can now answer the question of what is an object: it’s a bunch of properties - and, probably, something else. There is no exemplification relation, and objects and properties are not necessarily on the same abstraction level in this view: properties form, or constitute, objects. But in most views, objects are not entirely grounded in properties. Even in the most extreme accounts where objects are considered as just a bunch of properties and nothing else, a new metaphysical entity emerges - an object. It is material and physical, and can serve as causal relata. Properties, even if conceived of as modular tropes, although considered to be physical in a sense that they are building blocks of ordinary objects, are not physical in a sense that they exist independently of anything else.

Bundle Theories

Bundle theorists say that properties are the only constituents of objects. Hence the name, “bundle”: objects are bundles of properties.

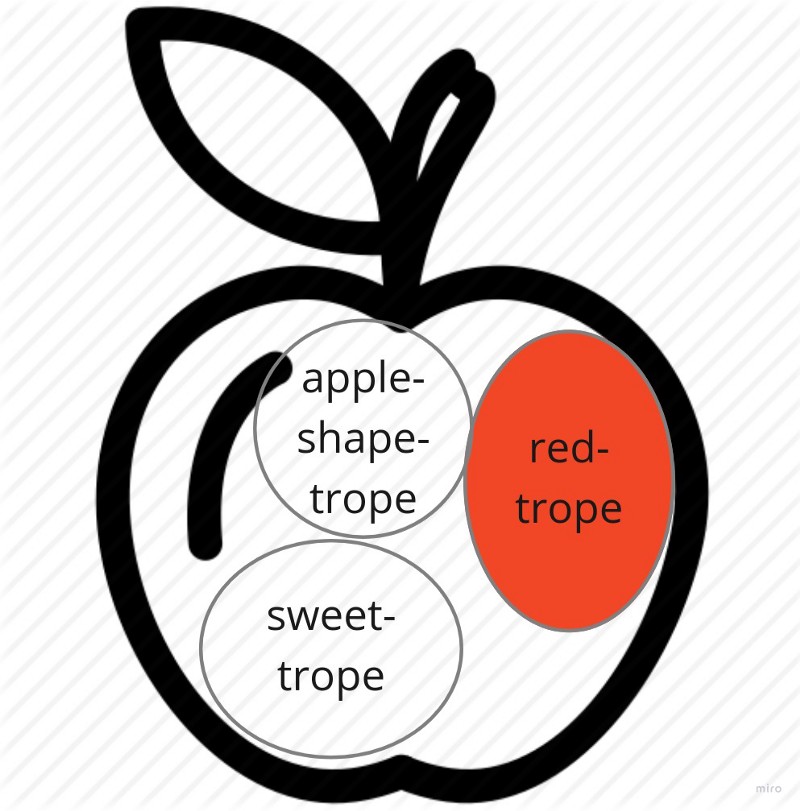

Trope Bundle Theory

This one represents probably the most intuitive combination: tropes, being a bit of both a property and an object, constitute a whole object. Thus, a physical object in this view is a bundle of incomplete objects, and each of them represents a specific property. As usual, any theory involving tropes has two branches: one goes with modular tropes, another with modifier ones.

Modular Trope Bundle Theory

One might think that this view faces the same issue as Modular Trope Relational Ontology. But if objects are just constituted of tropes, they do not duplicate the character of tropes. Instead, they possess character in virtue of having charactered tropes as constituents.

Put in another way, modular tropes both ground an object’s character and constitute it.

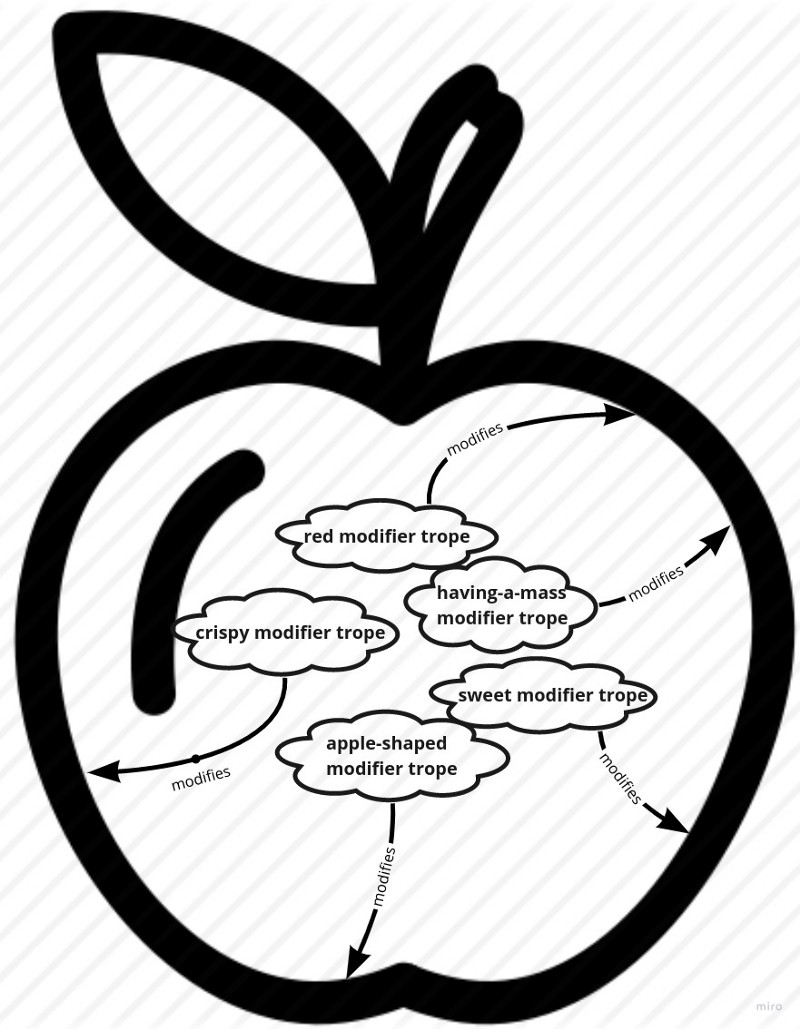

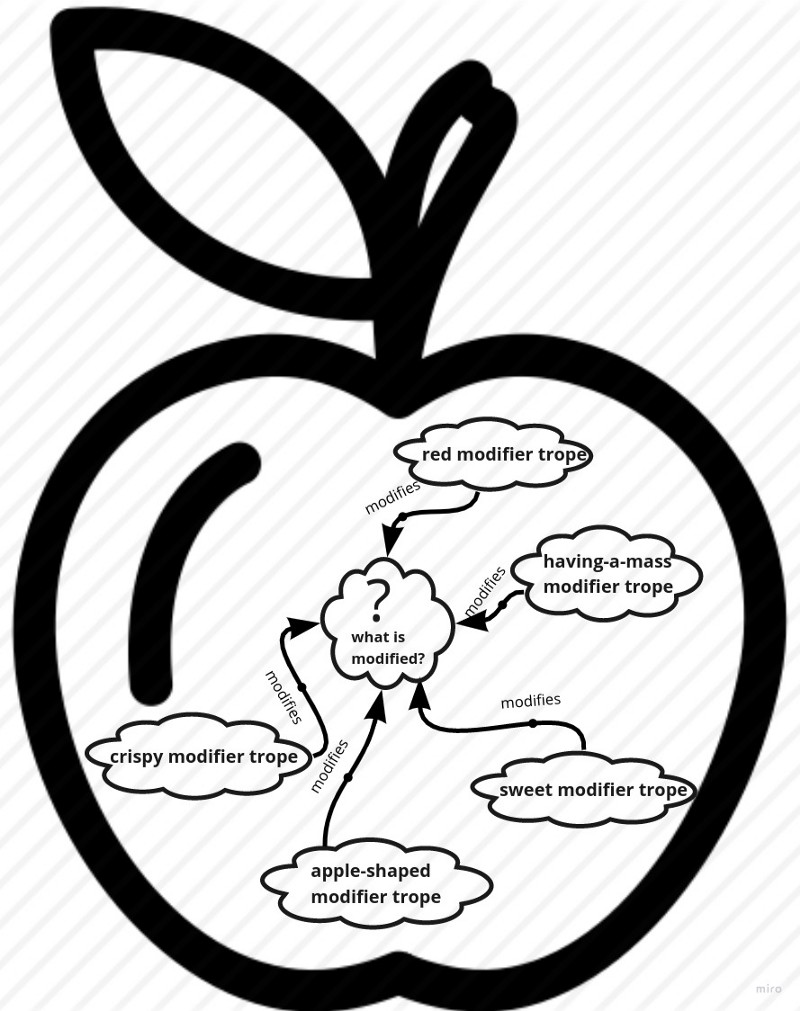

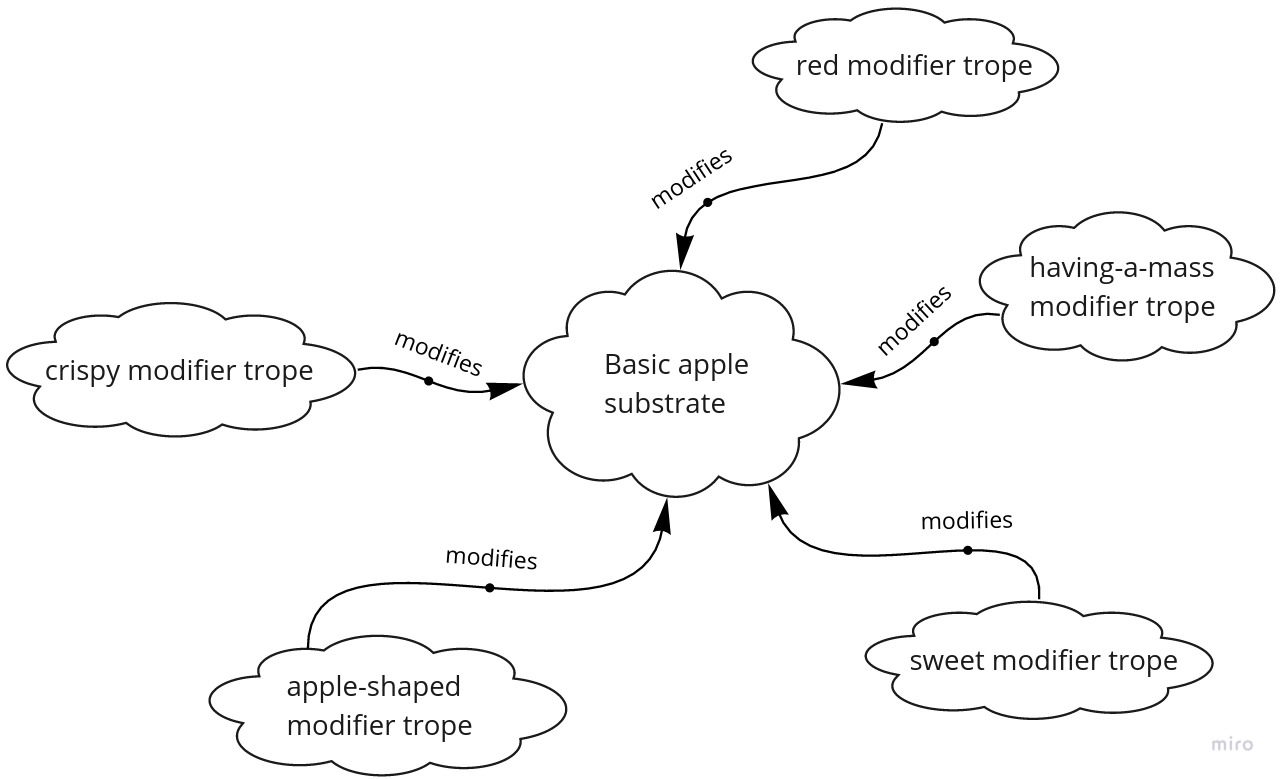

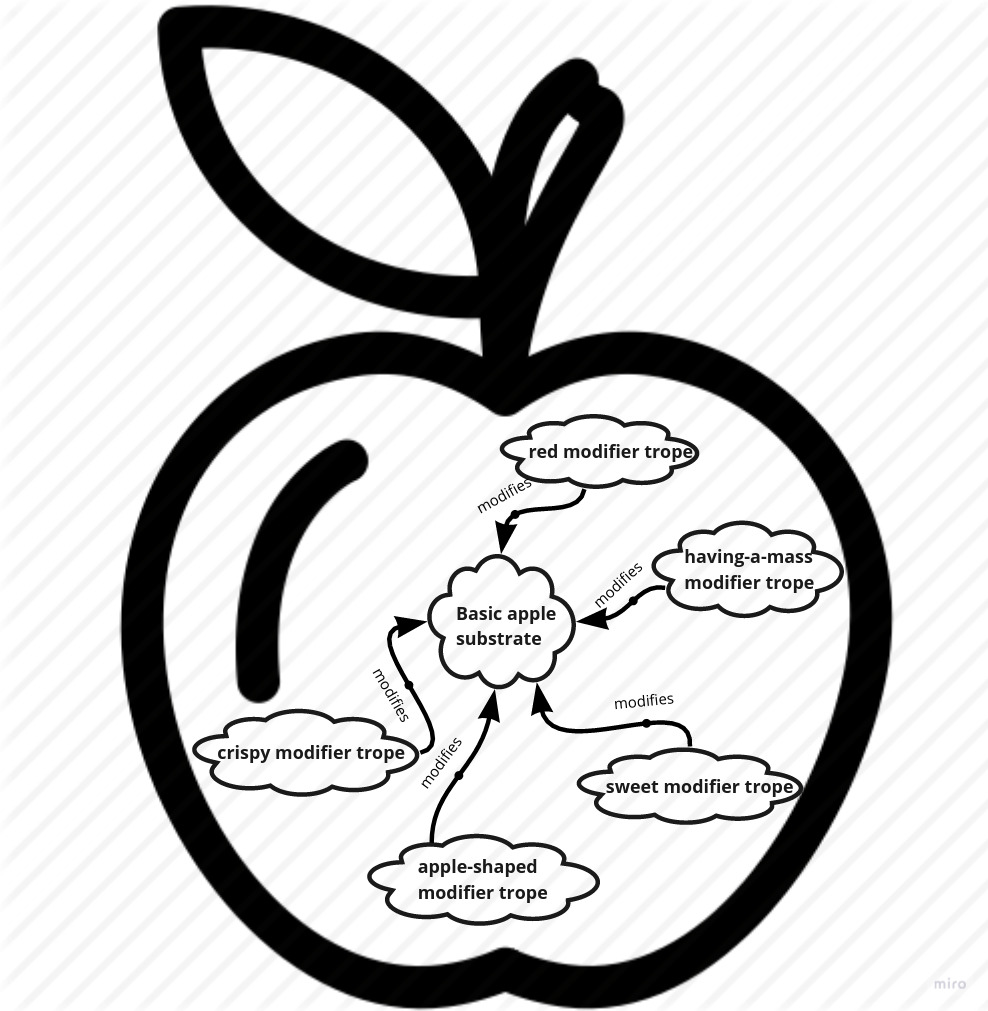

Modifier Trope Bundle Theory

If objects are just bundles of tropes, it’s not obvious what exactly modifier tropes are going to modify. There are just tropes, so it seems that they can modify only each other. But modifier tropes can’t have a character by definition. So we’re facing a contradiction here.

There are two possible solutions. The first one is that tropes modify the bundle itself.

After all, a house is not just a bunch of bricks. So an object is probably something more than just a heap, or mereological sum, of all its constituents. This sounds good, but it’s metaphysically vague. What exactly is the difference between an object and its constituents? Thus we can arrive with the second option postulating that difference explicitly as an entity not grounded in any way in properties, which is modified.

But in this case, we have to take a detour from a Bundle Theory in favor of a Substrate Theory, which postulates the desired entity called a substrate.

Classical Bundle Theory

This is an umbrella term covering several Realistic views. What they have in common is that objects are identified with sets of Universals they instantiate. Effectively, it plainly means that objects are sets of Universals. An interesting consequence is that proponents of this view have to accept the Identity of Indiscernibles Principle since there can not be two distinct identical sets.

Simple Bundle Theory

This is a view that objects are bundles of Universals. It’s committed to a sparse ontology of properties; for example, two Universals instantiated by some object don’t form a new one. Besides, not any set of Universals forms an object. It might be too small for grounding its character; for example, there is no such object which is just red. Or, it might not correspond to any object, like an orange elephant. So, Classical Bundle Theorist thinks of an object as not just any set of Universals, but a set of co-instantiated Universals. That is, there is at least (and, since Classical Bundle Theories endorse the Identity of Indiscernibles Principle, at most) one thing that instantiates all Universals from that set. So, to wrap it up, an object is a set of co-instantiated Universals.

There is a problem with this view: objects are incompatible with change. If any of the instantiated Universals ceases to do so, a new set emerges, as well as a new object. For example, right now I’m energetic, but two hours earlier I was a bit sleepy. But still, right now I’m the same person I was two hours earlier, in spite of the fact that now I possess some properties that I didn’t before.

Another problem with this Classical Bundle Theory is the same that Modifier Trope Bundle Theory has: it’s not clear what instantiates those Universals. You might promptly reply that an object does, but an object is a set of already instantiated Universals. So, what does instantiate them?

Nuclear Bundle Theory

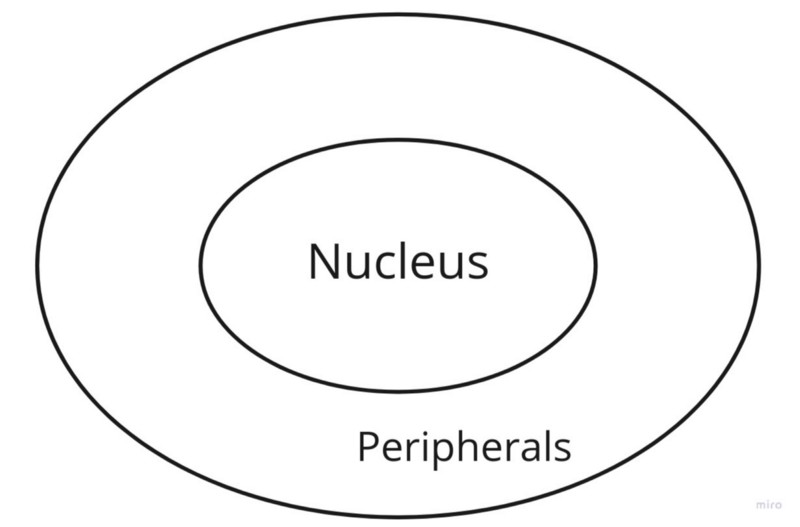

This view solves the first problem outlined above, an object’s incompatibility with change. It introduces the concept of Nucleus. It’s a set of Universals which represent only essential properties of the corresponding object. Consequently, objects are identified with a Nucleus, not with a whole set of properties. Thus, non-essential properties can mutate, but as long as a Nucleus remains intact, the corresponding object exists. The set of all the accidental properties is called Peripherals.

Nucleus effectively is a kind of an object it belongs to.

The fact that Classical Bundle theorists have to accept the Identity of Indiscernibles Principle, poses a problem for some. After all, it seems way too natural that two identical iron spheres are possible. In this case, proponents of this view must find something that grounds the distinctiveness of two identical objects. This issue is somewhat akin to the Hochberg-Armstrong objection, where two distinct truthmakers are needed to ground similarity and distinctiveness. And just as in Trope Theory this objection is dissolved with an introduction of finer-grained entities - tropes - here, we probably need to postulate some new entity grounding objects’ distinctiveness. So let’s see what exactly we can do.

Primitive Identity

This “solution” is effectively a rejection of the problem itself. It states that a pair of objects is self-individuating. Thus, according to this view, no new entity grounding objects’ distinctiveness is needed. The pair itself serves this role.

Haecceities

Haecceity is an identity property. It can only be exemplified by a single substance, and this is so by the very definition. For instance, the property of being Matt Berninger is a haecceity of Matt Berninger. This solution is supposed to be aligned with Constituent Ontology and the Principle of Constituent Identity, which states that two objects are numerically identical if their constituents are qualitatively identical. So two qualitatively identical iron spheres are possible since they have their own haecceity.

One prominent problem with haecceities is that they are quite mysterious. Being great in theory, no one seems to understand what they really are.

Substrate theories

The third option is to opt for one of the Substrate theories. Just to remind you, it solves two problems present in Modifier Trope Bundle Theory and Classical Bundle Theory: what does individuate objects, and what does instantiate their properties?

Basically, all of them boil down to a simple notion about objects, namely, that they have just two fundamental constituents: properties and a substrate. A concept of a substrate is introduced to solve at least two major Classical Bundle Theory issues. First, it solves an individuation problem: it is what grounds the distinctiveness of two identical objects. Besides, in Classical Bundle Theory again, as well as in Modifier Trope Bundle Theory, a substrate is a thing which instantiates Universals or is characterized by Modifier Tropes, respectively. So you can think of a substrate as a very, very basic object.

There are two varieties of a Substrate Theory: Trope Substrate Theory and Classical Substrate Theory. They differ only by the substrate character dimension. In Trope Substrate Theory, substrates are multi-dimensional, and in Classical Substrate Theory, they are either one- or zero-dimensional. Interestingly enough, the “classical” part in Classical Substrate Theory has nothing to do with Realism. It only tells the dimension of a substrate: either zero or one. Multi-dimensional substrates are problematic. They are nothing but ordinary objects, hence they beg, in turn, their own substrates. Thus, we find ourselves in a vicious regress.

Classical Substrate Theory is more lasting. The view endorsing one-dimensional substrates is called a Modular Substance Theory. Modular, because in this view, substrates are, or at least are somewhat akin to, modular tropes. Another flavor goes with characterless substrates, and it’s called a Bare Particular Theory.

Modular Substance Theory

A substrate in this view is the most basic object of the corresponding kind. For example, APPLE is the kind of an apple in front of me. Its substrate is a mere apple, the most basic apple of all. Moreover, it’s advertised as one-dimensional. In other words, the only way we can characterize it is that it is an apple. “Being an apple” is the only dimension its character has, and it defines the kind of its substance.

The problem with this view lies on the surface: even the most basic apple has a shape, a color, and a taste. This sort of problem is known as a thickening problem; it is a supposed-to-be thin character that thickens. As a possible solution, we might say that a substrate must have only one property in itself, and nothing prevents it to have an extrinsic properties. In other words, we can assume that substrates either exemplify Universals, or are modified by modifier tropes. Important note: those properties are extrinsic to a substrate, not to an object! For example, a red, sweet and crispy apple has a single-dimension substrate - a basic apple, and intrinsic properties of being red, sweet and crispy. Besides, those properties are constituents of that apple. That is, an apple doesn’t exemplify them; instead, it simply has them.

But delving a tad deeper in metaphysical analysis, we may find out that an apple has intrinsic properties because its substrate stands in specific relations with corresponding properties which are extrinsic to it.

So, all of a sudden, we have a relational ontology inside of a constituent one.

Bare Particulars Theory

It’s really close to the Modular Substance Theory, except that substrates have no character whatsoever; in other words, they are bare particulars. They act like a peg that strings all the properties. And just like in the Modular Substance Theory, bare particulars still have the character, but not in themselves, but in virtue of standing in exemplification relation with properties. But, once again, an object itself doesn’t exemplify properties; it has them as constituents.

An image I bear in mind for this view is a set of weight plates strung on a loading pin. If you’ve ever been to a gym, you might know what I mean. Here they are separately:

And as a whole:

To me, this view of substrates is reminiscent of Aristotle’s concept of the Matter. It’s unintelligent, but essential for an object’s existence.

Objects’ ontology from a bird’s view

Further reading

First of all, this entry relies quite heavily on Chapter 5 of the Fundamentals of Metaphysics, so I think it’s fair to put it at the very beginning of a reading proposal section. The rest of the readings in its entirety belongs to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and I won’t mention this fact further.

Probably the best place to start your endeavors on what an object is, what it’s not, what it can do and the like, is an Object article. There are several finer-grained topics that probably deserve your attention.

This entry on a reference is a thorough analysis of, well, reference: what is its nature? How does a reference works, what is its mechanism? Literally, what do I mean when I say “Bryce Dessner”?

An article on existence tries to answer the question of whether existence is a property of objects, and consequently, are their any objects that lack this property? Spoiler alert for those who want to read it: existence is not a property, and there are no nonexistent objects. It seems that the only guy who had the guts to say otherwise was Alexius Meinong, and here is an entry on nonexistent objects.

This post on the Identity of Indiscernibles considers the issue of what it takes for qualitatively identical objects to be distinct, and whether it’s possible at all. An by the way, I bet you’d be surprised to find out there is a full-blown entry on identity itself.

This post shatters the very fundamentals of your understanding of the world around you. There are puzzles that strongly indicate that there are no apples, fire trucks, and hydrants. On the other hand, there are accounts that claim very persuasively that the Eiffel Tower and my left big toe form an object that is no more strange than a keyboard I’m currently typing these words with. If you feel excited, check it out. The language is accessible, which is not usually the case for SEP, and all in all it’s a fun read.

An entry on substances offers both historical and contemporary perspective on a concept of substance. On some accounts, it’s the same as the concept of an object. For me, the views of Aristotle and John Locke are extremely interesting, that’s why I’ve included them in this post.

Despite being a bit off the track, there are a couple of entries on object classification that I really enjoyed. The first one is about several attempts to find some single ontology of everything in the world, and more often than not, objects played a significant role in it. The second one is the intersection of different ideas: substance, object, and their classifications. It’s highly abstract and not an easy read, but well worth the effort.

Last but not least, this entry on tropes takes a really deep look at them.