The Truth

April 14, 2020 • 9 min read •The concept of truth seems ubiquitous. But what is it exactly? And what does it mean for something to be true?

The answer has three components. First one considers an entity that can be either true or false, that is, has a truth value. It’s called a truthbearer. The second component is an entity which grounds, or entails a truthbearer’s truth value; it’s called a truthmaker. And the third one is a relation between a truthbearer and a truthmaker.

The Correspondence Theory of Truth

Right now, on March 31, 2020, at 8:54 am, as I’m writing this sentence, I’m drinking an overwhelmingly nice cup of flat white. I can write the following sentence: “I’m drinking a cup of flat white”, and it is true because I’m actually doing this.

This intuitive understanding of the truth dates back to Aristotle who posited it like the following:

A sentence is true if the world is the way the sentence says, and false if the world is not the way the sentence says.

This view is called the Correspondence Theory of Truth.

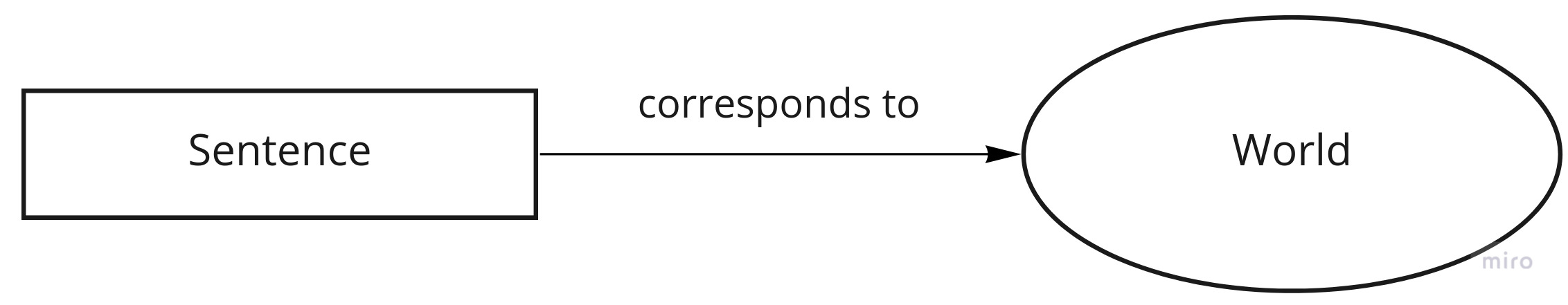

Correspondence is a relation, namely the relation between two things: a sentence or thought, and the way the world is. This relation is a metaphysical bond between the two. When it exists, a sentence is true. Or, less formally, when a sentence corresponds to some actual way the world is, it’s true.

Otherwise, when there is no correspondence relation between a sentence and a world, the world is not the way a sentence says, and a sentence is false.

This relation is what we can call a “truth” in the Correspondence Theory of Truth.

Propositions

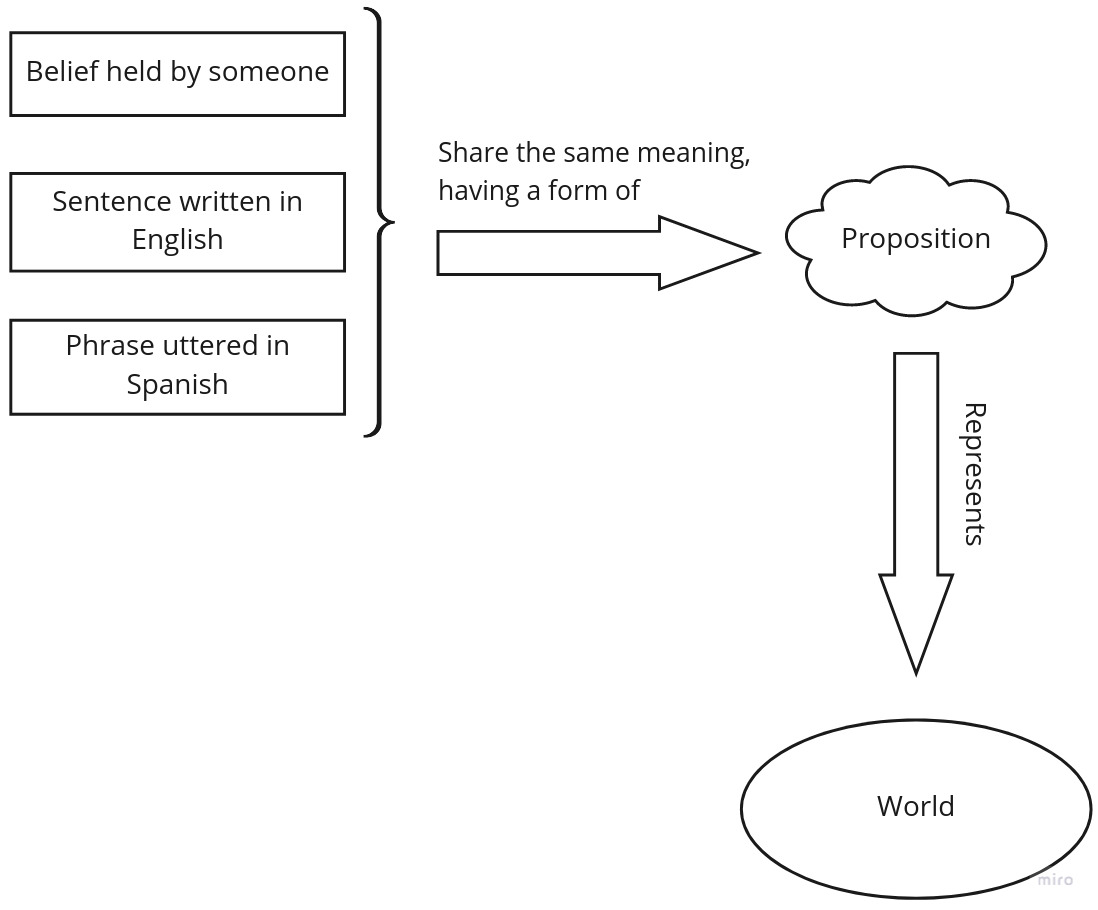

Imagine a guy sitting next to me and watching me drinking a cup of flat white. He might utter “Este chico está bebiendo un flat white”. In Spanish, it means “This guy is drinking a flat white”. The meaning of that utterance and its textual translation in English is the same. And there are always multiple ways to express the same meaning.

The concept of proposition reflects this idea. A proposition is a language-independent meaning of a sentence or some other mental entity, like thought, belief, or desire.

The concept of proposition takes Aristotle’s Correspondence Theory of Truth a little further. Instead of sentences corresponding to the world, we have a more general concept - a proposition. It’s an abstract entity, free from human conventions, which represents the world somehow.

Propositions that are true are often called “truths” as well. But what exactly should a proposition correspond to in order to be true?

Classical Truthmaker Theory

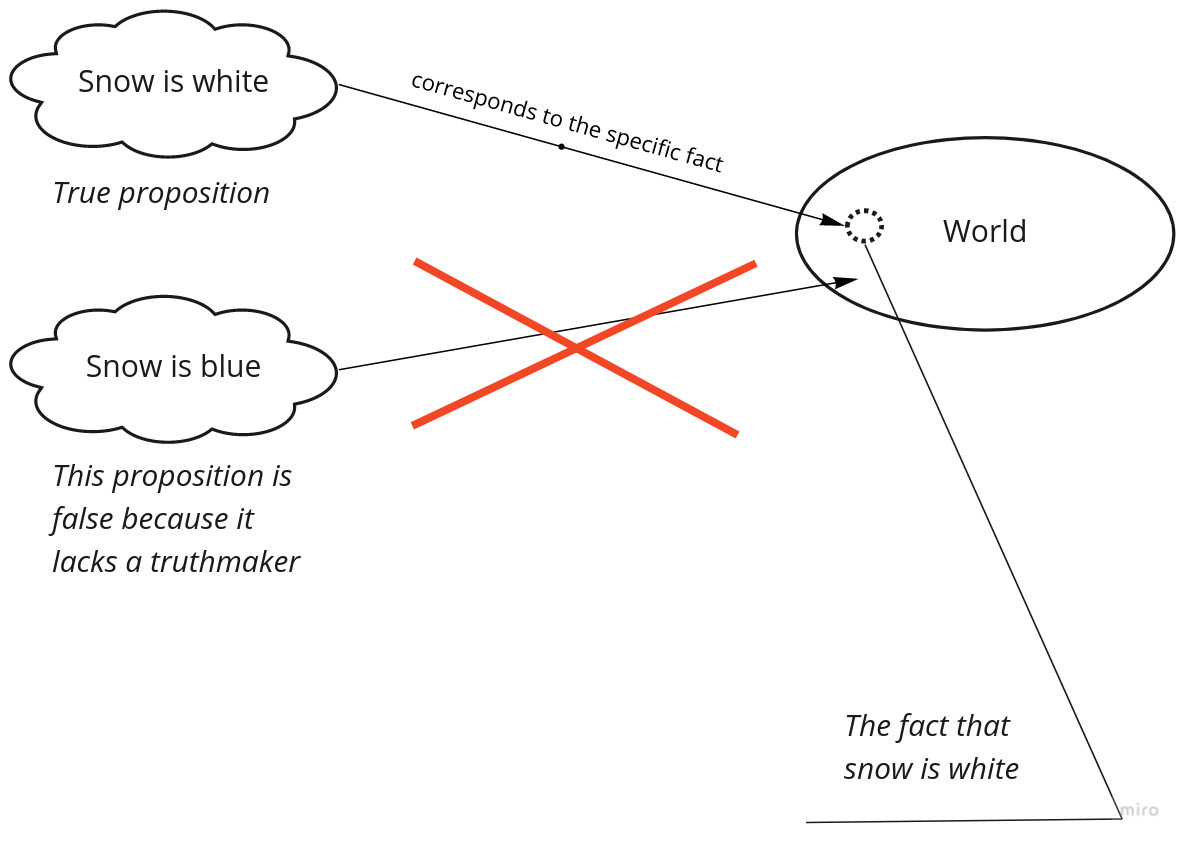

Truthmakers are parts, or bits, of the world that make propositions either true or false. Most commonly, facts are accepted to be those parts. For example, the fact that I’m drinking a cup of flat white explains why the sentence “I’m drinking a cup of flat white “ is true. Here is a more formal definition:

X is a truthmaker for the proposition p if and only if: 1. p must be true if X exists; 2. if X exists and p is true, then p must be true at least in part because X exists.

Here are some arguments for truthmakers.

First, the Correspondence Theory of Truth, being the most widely accepted theory of truth, naturally leads to truthmakers. It’s a specific thing in the world that propositions correspond to.

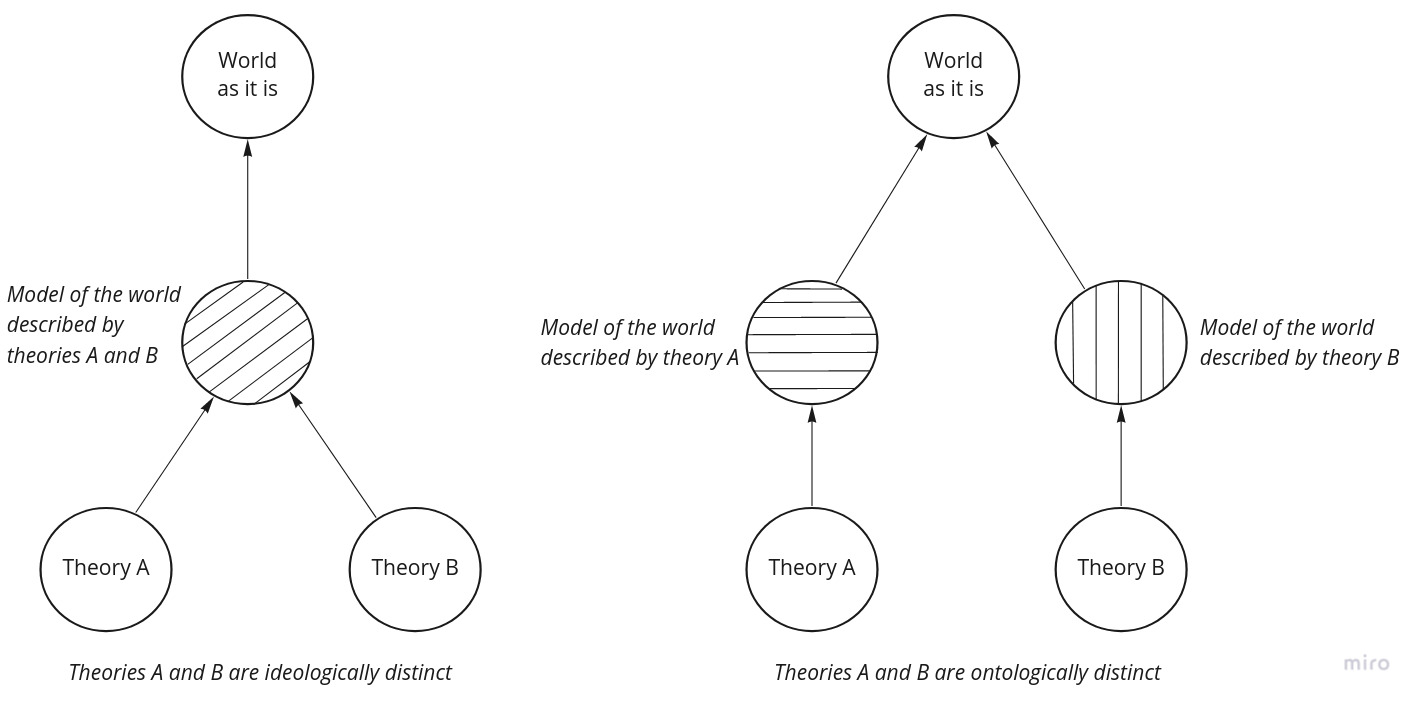

Second, truthmakers help us to distinguish between ideologically and ontologically distinct theories. Theories are ideologically distinct if they describe the world similarly but using different terminology. On the contrary, theories that describe the world differently, are ontologically distinct.

For example, there are two theories. The first one says that there are tomatoes and cucumbers. The second one claims that there are Solanum lycopersicums and Cucumis sativuses. Those theories simply use a different naming, so they are ideologically distinct.

Now take another two theories. The first one says that there are just bananas and oranges, and the second one insists on apples and mangoes. The world’s ontology is different in those theories. So they are ontologically different.

Third, truthmakers can be employed to catch metaphysical cheaters. Here is what a dialogue with a metaphysical cheater, Vince, looks like:

Vince: I believe that p is true.

Me: Why?

Vince: Because!

Vince is a cheater because he refuses to ground the truth of a proposition p.

Two Varieties of Classical Truthmaker Theory

Truthmaker Maximalism

It’s a view that every truth has a truthmaker. But there are a couple of problems with this stance.

The first problem is a negative assertion, such as “There are no unicorns”. What kind of entity is supposed to ground this claim? It seems that this sentence is true not because something exists, but because something doesn’t - namely, unicorns.

The second problem is closely related to the first one. It’s about universal generalizations, that is sentences like “all stones are solid”. Assertions like that are quite brash, from a metaphysical perspective at least. We need a very powerful truthmaker for that. It should ground the truth that any stone is solid and that anything else is either not a stone or not solid, or doesn’t exist at all (like non-solid stones). In other words, it fixes both what exists and what doesn’t, thus automatically solving the problem of negative assertions. This requires an astronomical amount of brute facts. This set of brute facts is called the Totality Fact. It solves these two problems, but, from Occam’s Razor perspective, the cost is huge.

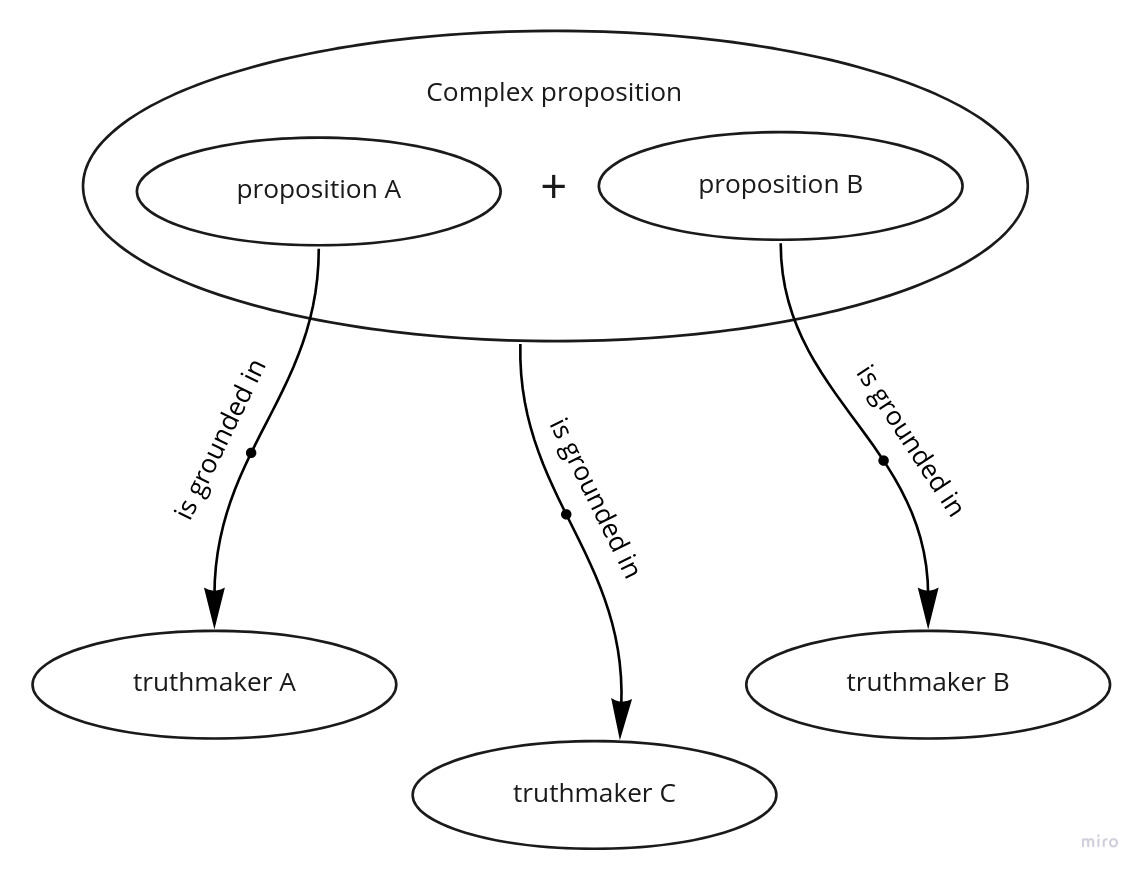

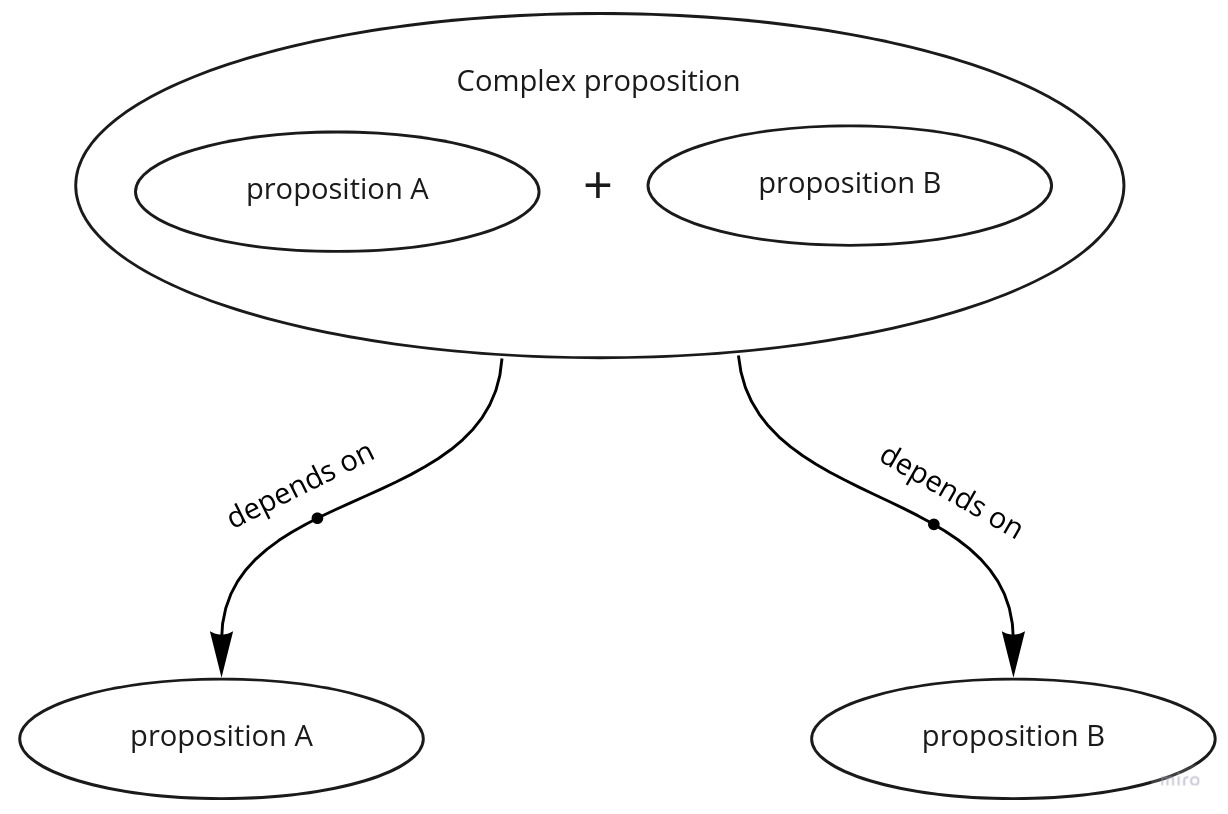

The third problem concerns the fundamentality of conjunctions. Consider a sentence “I’m drinking a cup of flat white”. It’s true by the way because I’m still drinking a cup of flat white right now. This fact is a truthmaker for that sentence. Besides, I’m writing this post. Hence, the sentence “I’m writing this post” is true. Now consider the following sentence: “I’m drinking a cup of flat white and writing this post”. If truthmaker maximalist is true, this conjunction must have its own truthmaker. Once again, Occam’s Razor claims that this is unpalatable.

Besides, conjunctions seem to be less fundamental than the parts they consist of. After all, a conjunction is true because each of its parts is true, not vice versa.

Truthmaker maximalist doesn’t embrace it, but Atomic Truthmaker Theory does - let’s take a look at it right now.

Atomic Truthmaker Theory

“I’m drinking a cup of flat white” is a simple and positive statement that can’t be decomposed any further. Such kind of truths is called “atomic” in Atomic Truthmaker Theory. And only such kinds of truths have truthmakers. More generally, atomic truths pose either the existence of a single thing (“there is a cup of flat white in front of me”), or a single thing possessing a single feature (“my cup of a flat white is warm”), or several things standing in a single relation (“a cup of americano is hotter than a cup of flat white” or “I’m drinking a cup of flat white”). Conjunctions and disjunctions represent complex truths. Conjunctions, having the form of “p1 and p2”, are true if both p1 and p2 are true. For example, “I’m writing this post and drinking a cup of flat white” is true if I’m doing both of those activities. Disjunctions are true if either of their constituent truths is true.

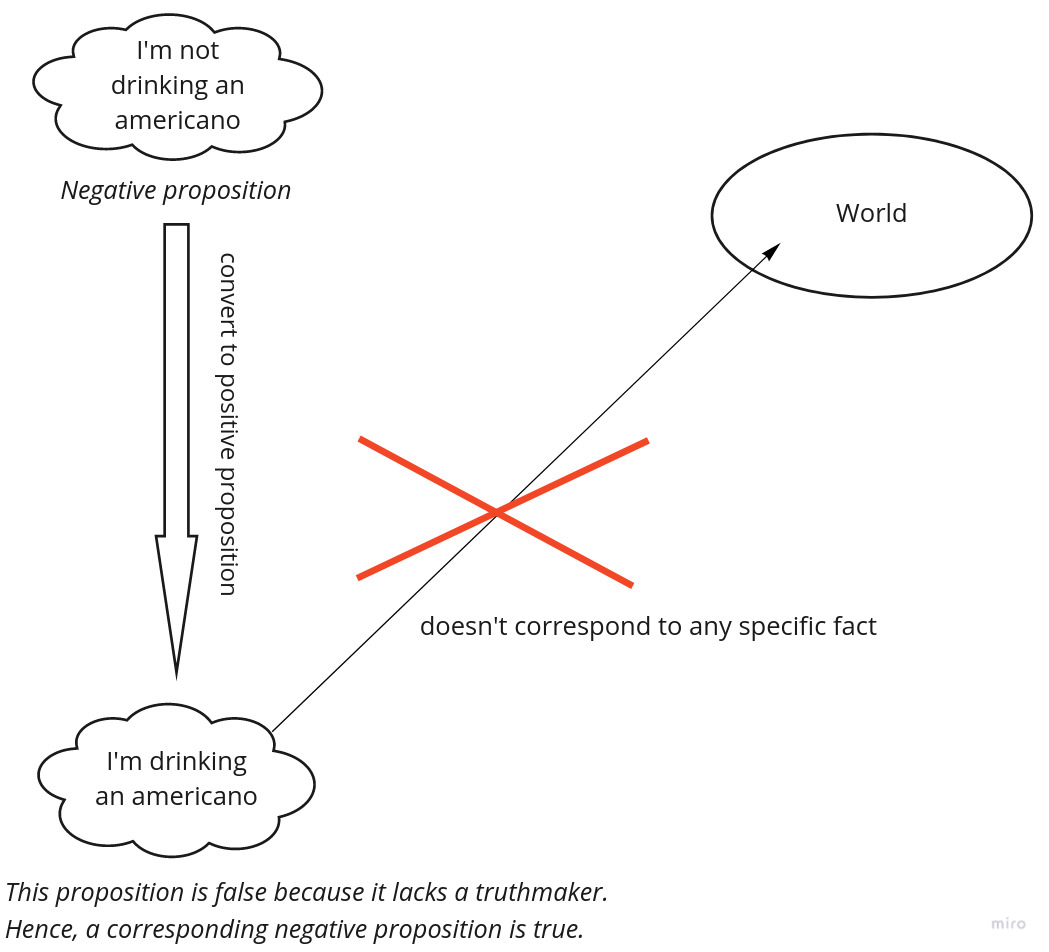

Now consider the following negation: “I’m not drinking a cup of americano”. This sentence is true because “I’m drinking a cup of americano” doesn’t have a truthmaker, not because “I’m not drinking a cup of americano” does.

At least two problems arise here. First, a negative proposition doesn’t correspond to anything - and Atomic Truthmaker Theory operates within The Correspondence Theory of Truth realm. Second, the truth of p isn’t related to the falsity of non-p: there is nothing that can ground their interconnectedness. Probably we need to adjust our understanding of either a nature of correspondence relation or an entity it corresponds to, that is, a truthmaker.

Additional Argument for Truthmakers

Besides three previously mentioned arguments for truthmakers, there is one more, existing in the scope of Atomic Theory. Truthmakers can give an account of fundamental truths, that is, truths having a single truthmaker. Those fundamental truths are just atomic truths. That’s where Atomic Theory beats Truthmaker Maximalism.

Deflationism

In Correspondence Theory, when some proposition is true, it has a property of being true in virtue of correspondence relation. Deflationism denies that we need this property. According to it, to say that something is true is just a more verbose way to say that something simply is. So instead of saying “It’s true that I’m drinking a cup of flat white” I can just say “I’m drinking a cup of flat white”.

Objections

All our values, even the deepest ones, are based on faith. And any faith by its very definition is built upon something you consider to be true. For example, I believe that stealing is wrong, and hard work is right. Thus, for me, “One should work hard” has a property of being true.

Besides, the traditional view of knowledge is deeply rooted in the concept of truth. We can’t know things which are false. For example, we don’t have any chance to know that Hillary Clinton has won the US Presidential election in 2016 - because she has lost.

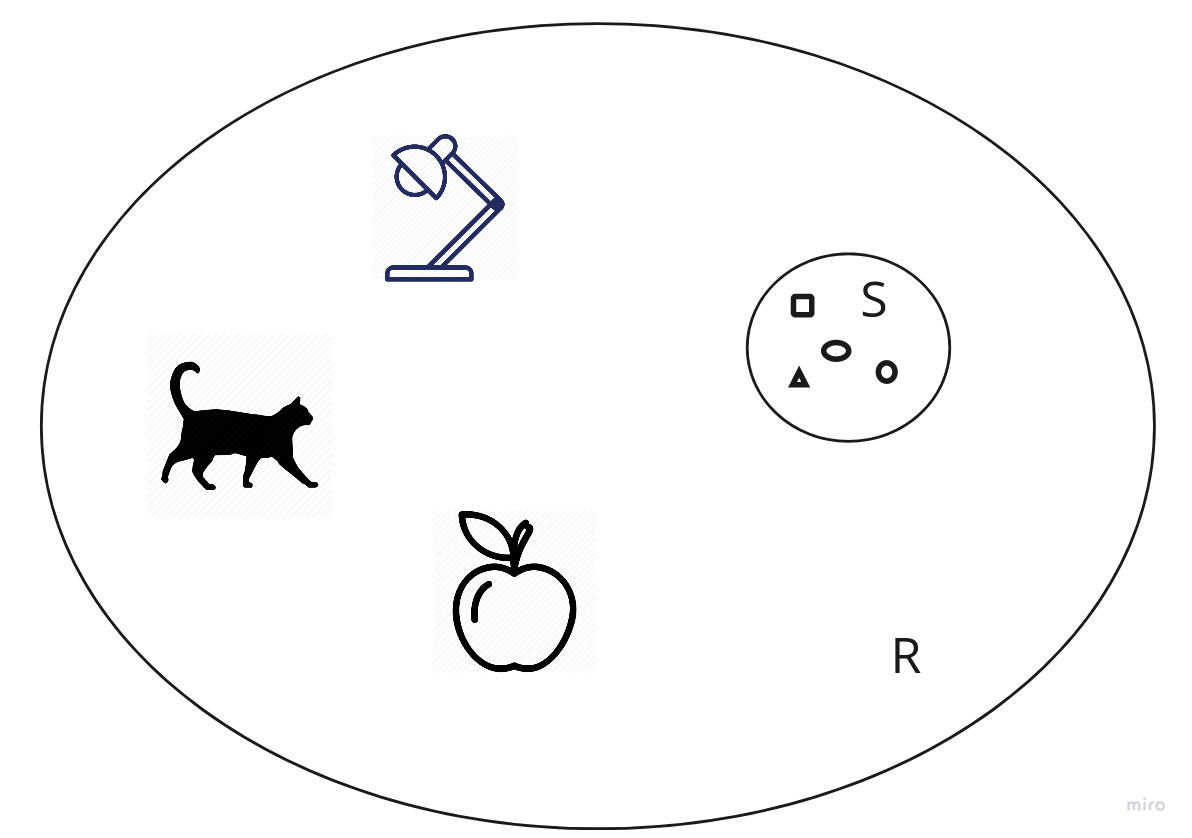

Truth Supervenes on Being

Generally, supervenience is a specific relation between sets. Set X supervenes on a set Y if and only if you can’t change some element in X without changing some element in Y. In other words, a set X is fixed by a set Y. Or, we can say that a set X depends on a set Y.

Classical Truthmaker Theory postulates that a proposition is true in virtue of correspondence to a fact from the real world. Truth Supervenes on Being takes a broader perspective on the nature of this correspondence relation.

First of all, it goes in two flavors: strong and weak. Strong version defended by John Bigelow1 postulates the following:

If something is true then it would not be possible for it to be false unless either certain things were to exist which don’t, or else certain things had not existed which do.

Thus, Truth Supervenes on Being goes hand in hand with Atomic Truthmaker Theory concerning true positive atomic propositions: it’s not possible for them to be false unless their truthmakers had not existed. Besides, it fills a truthmaker gap in negative propositions like “There are no unicorns”. It’s not possible for it to be false unless certain things, namely, unicorns, existed; but they don’t. Thus, we don’t need a Totality Fact for that, it’s enough to not have a falsitymaker, that is, unicorns. Universal generalizations are treated the same way. “All stones are solid” is impossible to be false unless non-solid stones existed, but they apparently don’t.

In other words, true propositions, or truths, supervene on the ontology of the world, on things that exist and that don’t.

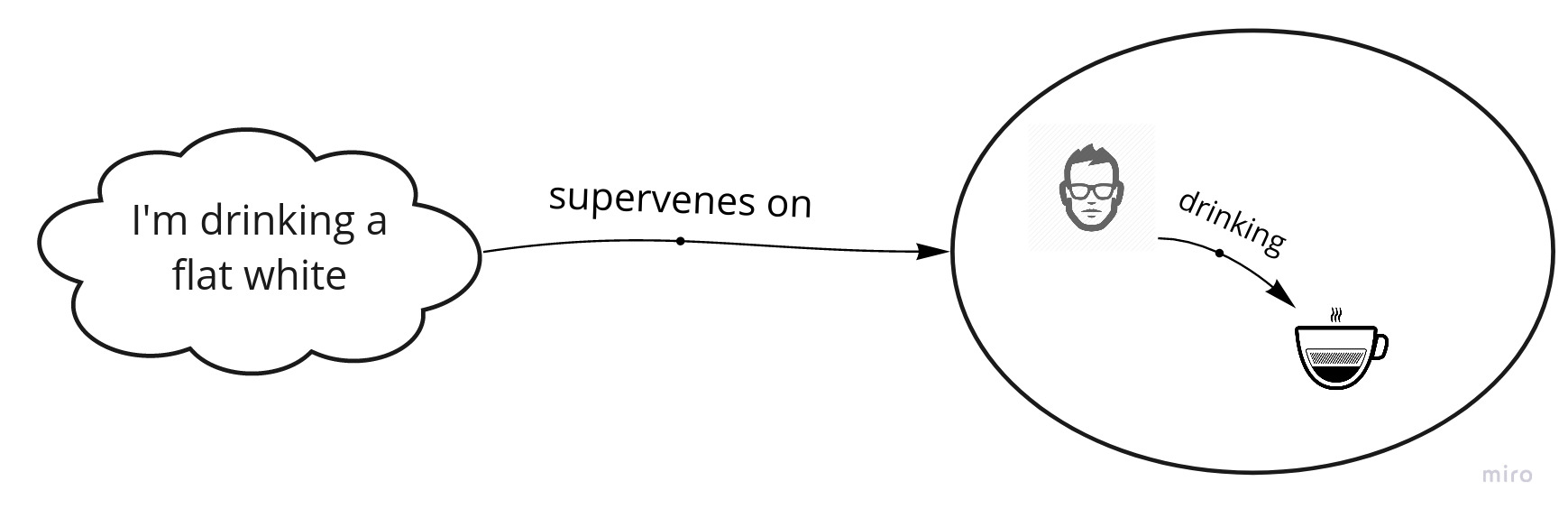

The weaker version implies that truth supervenes not only on existence or absence of specific entity, but also on an entity having specific properties, or a set of entities standing in specific relations with each other. In this version, the proposition “I’m drinking a flat white” doesn’t require a truthmaker. It supervenes on the world having me drinking a flat white. If this proposition was false, there would be some differences in the world, such as me drinking an americano instead.

Truth Supervenes on Being addresses the issue with unrelatedness of truth of a proposition p and falsity of non-p. Consider for example a proposition “Snow is white”. It’s true in virtue of our world being such that snow has specific properties, one of them is being white. And this results automatically in the falsity of propositions like “Snow is red”, “Snow is blue”, etc - because snow has the property of being white, not red or blue.

Further reading

I gave an overview of different perspectives on the concept of truth and what it means to be true. It’s by no means an exhaustive one, and it wasn’t supposed to be such. There are a lot of publications that take a deeper dive.

Fist of all, there is still no consensus in the nature of the relation between a truthbearer and a truthmaker. This stanford entry on truthmakers suggests different views on that.

Here on the internet encyclopedia of philosophy and here on stanford entry on truth you can find an overview of existing theories of truth in greater detail.

Besides, iep has a nice overview of truthmakers and how they fit in other areas of metaphysics.

If you want to dive deeper in the Correspondence Theory of Truth, check out this one.

-

Bigelow, John. 1988. The Reality of Numbers: A Physicalist’s Philosophy of Mathematics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ↩