Natural Kinds

February 1, 2021 • 14 min read •There are plenty of ways to classify stuff around us. Often times though, we might feel that there is a way that outstands among others. It reflects human-independent aspects of the world, not our classification practices or specific interests; it’s discovered rather than invented. We refer to kinds classified this way as natural. Typically, we assume that science is pretty much successful in discovering those kinds. Paradigmatic examples include chemical elements and physical particles. In this post, I’ll take a look at different ways to classify reality, and whether we, humans, have anything to do with it.

Different Views on Reality Classification

There are actually just two views on that. Realism is an umbrella term for all accounts regarding that there are natural classifications independent of human interests and aims. Anti-realism is a term covering the views at the opposite end of a spectrum; in one way or another, they all imply that there is no such thing as natural classification.

Naturalism, a Realist’s View on Classifications

Naturalists endorse a view that classifications exist independently of our beliefs, classification practices, values, etc. In other words, those classifications exist independently of us; they reflect the world as it is, not as we’ve decided to categorize it. Basically, that’s what Scientific Realism is all about: the structure of the world, and of reality we inhabit, is mind-independent. In its strong form, naturalism implies that there is a single way to classify any domain. In looser accounts, there might be multiple ways to do that, and for that reason, the resulting view is called Promiscuous Realism. Besides, it’s very likely that human interest starts to creep in.

Promiscuous Realism

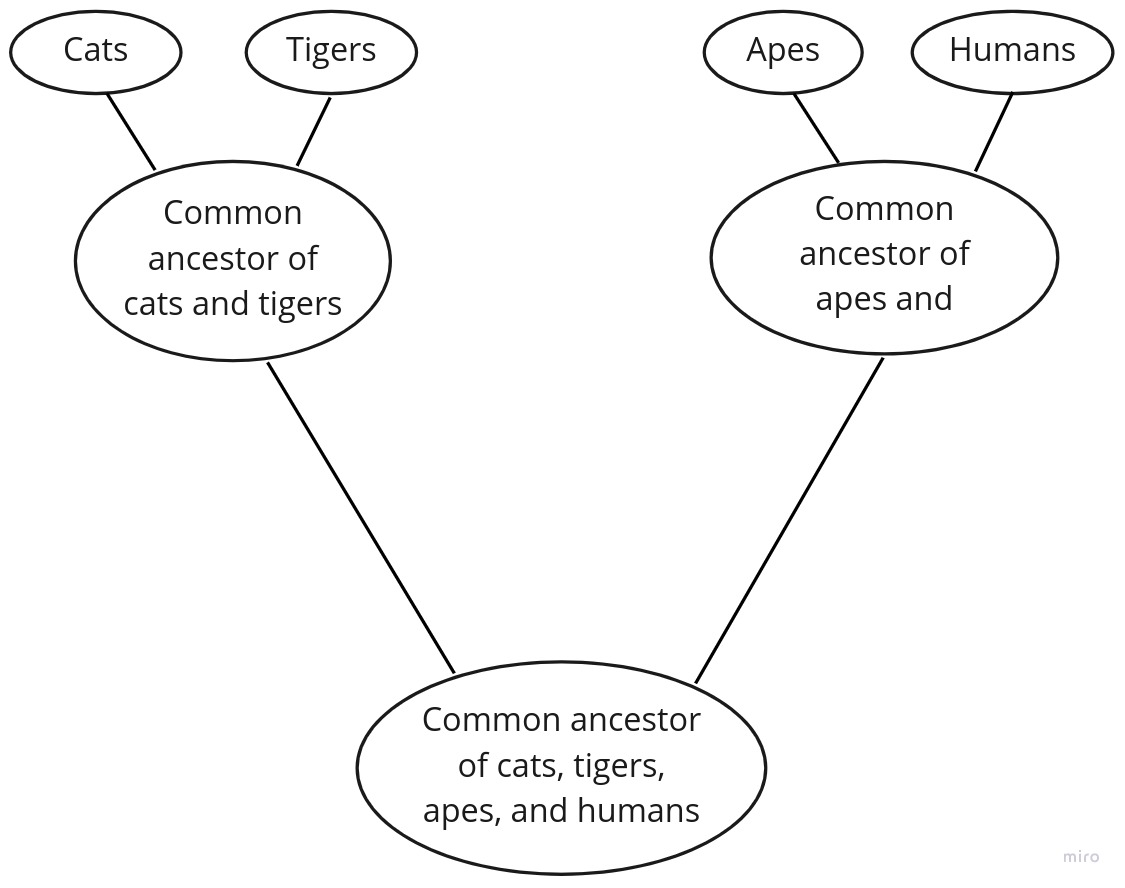

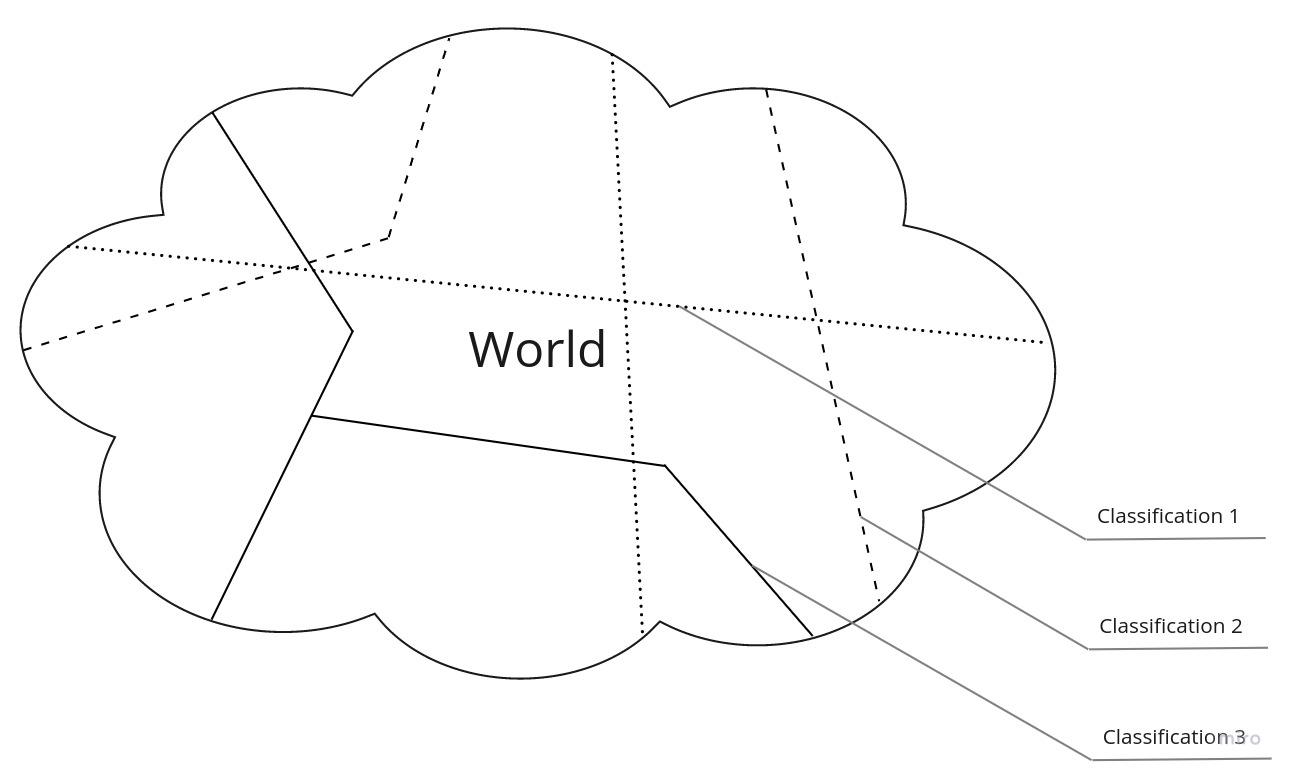

It’s a view that the world is quite a complex thing and there are multiple mind-independent, natural classifications that can be used in any particular case depending on our interest. Personally, I refer to this view as Multiple Naturalism, though it’s not a ubiquitous term. For instance, if we’re interested in radioactivity, we can classify chemical elements accordingly. In biology, if we’re interested in common properties, we can use the Linnean classification that is based on species’ similarity. If we want to take evolutionary changes into account, Cladism might be a good fit: the primary classification criterion is the proximity of different species’ common ancestor.

Looking at this image, one can derive that cats and tigers are closer to each other than cats and humans, for instance.

One strategy to show that Promiscuous Realism is indeed a realistic view is to treat kinds as domain-dependent. It doesn’t require all rational enough humans with different aims to reach the same classification. Instead, it implies that all rational enough humans sharing the same aims reach the same classification within a specific domain. Apparently, it’s not a puristic naturalist’s view, but it still can count as Realism.

Conventionalism

This is a typical anti-realistic view. It boils down to the notion that there is no such thing as kinds independent of us, classifiers. The very fact that the process of classification involves the human mind indicates that the result is not human-independent by definition; it inherently and inevitably reflects the aims and interests of us, classifiers. In this view, kinds are constructed rather than discovered; entities in nature are dependent on human beings, our conventions, and interests.

This position has a weak and a strong form. Weak Conventionalism assumes that the basis for classification is a Real Essence - incomprehensible internal structure that defines all the object’s properties. Hence, despite truly natural classifications exist, we humans can never discover them. Strong Conventionalism, in turn, denies that there are natural classifications whatsoever.

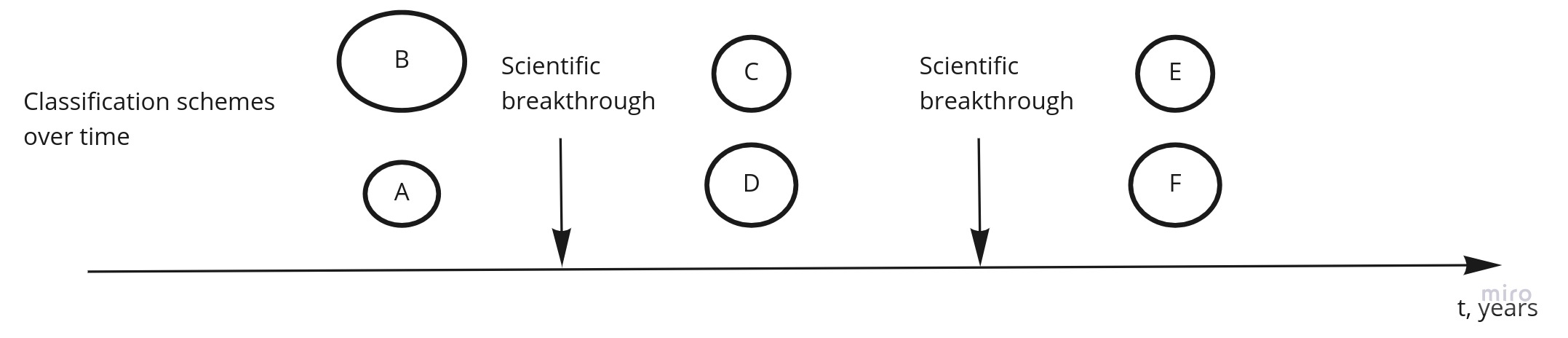

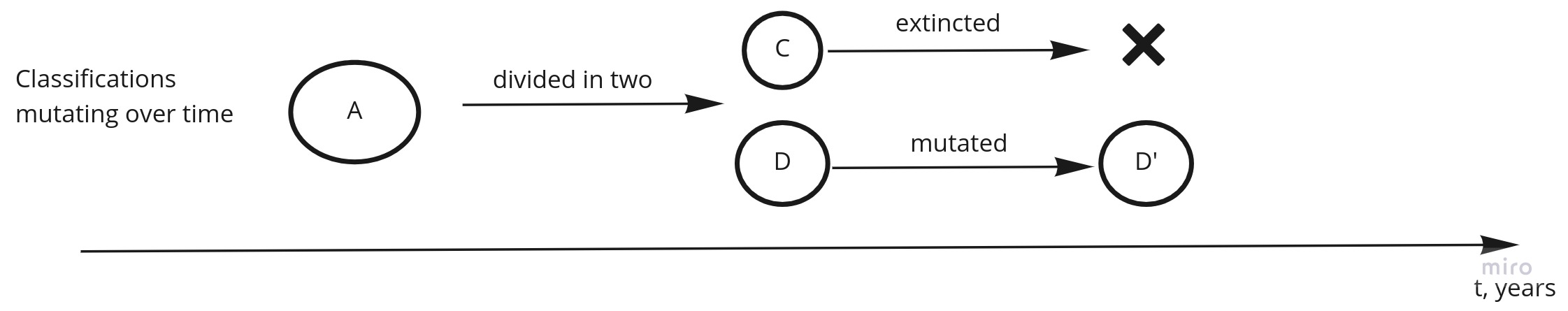

Conventionalist kinds have a significant drawback. Since they rely on our interests and depend on our classification practices, they are inherently less objective and less stable. After all, our interests may change, our classification practices may do either as the science moves forward. This leads to the unpalatable conclusion that any kind can change over time.

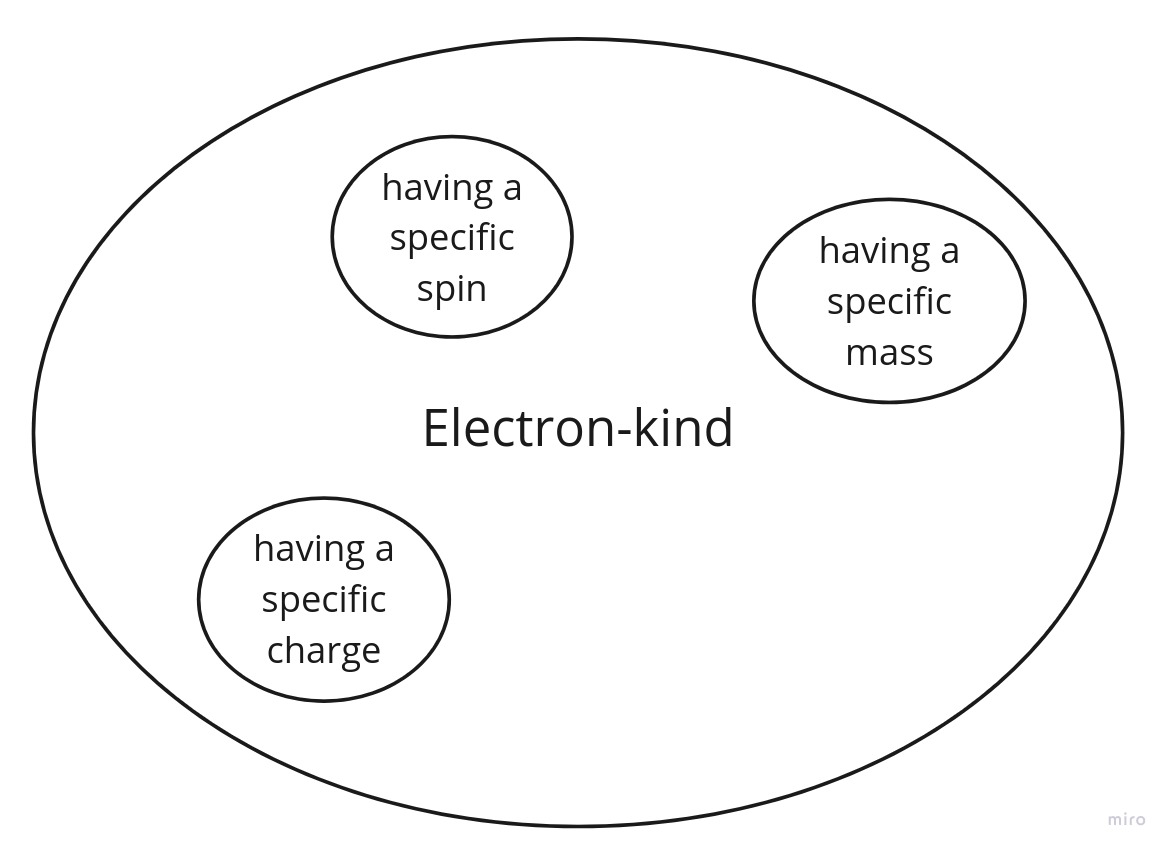

But conventionalists want their classifications to be stable, too; they have epistemic and pragmatic needs, after all. They want to take advantage of inductive inference. For instance, conventionalists want to take for granted that if something is identified by any observable property as an electron, then it has a guaranteed set (or a subset, in looser accounts) of properties specific for an electron, like having a specific mass, spin, charge, etc. In order to achieve this stronger inductive inference, there should be lots of evidence of properties specific to the kind at hand. In other words, kinds must contain many members, the more the better. This increases the certainty that any new instance of a kind identified by some observable property will possess the specific behavior.

For example, there are a lot of electrons that physicists have been observing over the last hundred-something years. All of them have been proved to have the same properties. So, nowadays we can rest assured that if some particle has a specific trajectory and mass and thus is identified as an electron, then it has a specific charge and mass - properties that define an electron.

Thus, anti-realists have to take some faint efforts towards objectiveness in their search for stability: they have to accept that some kinds are more objective than others, and this objectiveness transcends their aims and interests. And that’s the point when those kinds can be seen as the natural ones. This position gets too close to realists’ camp.

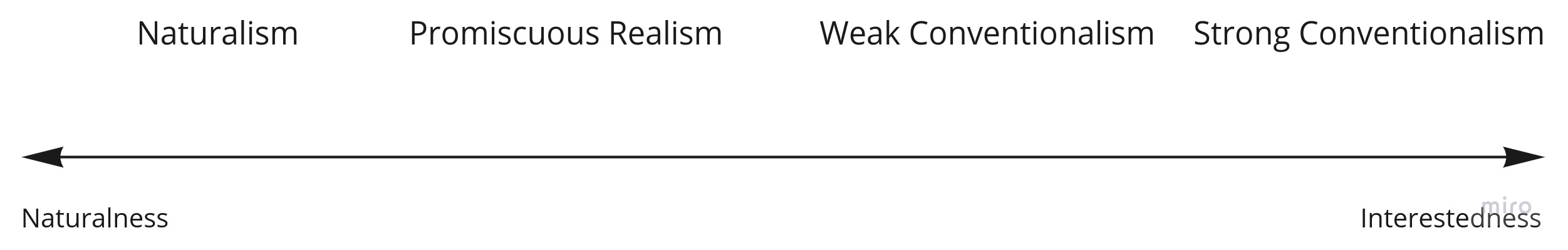

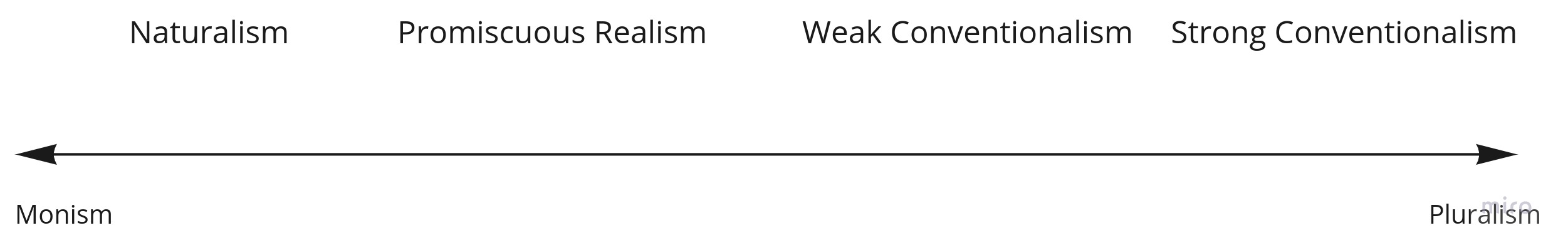

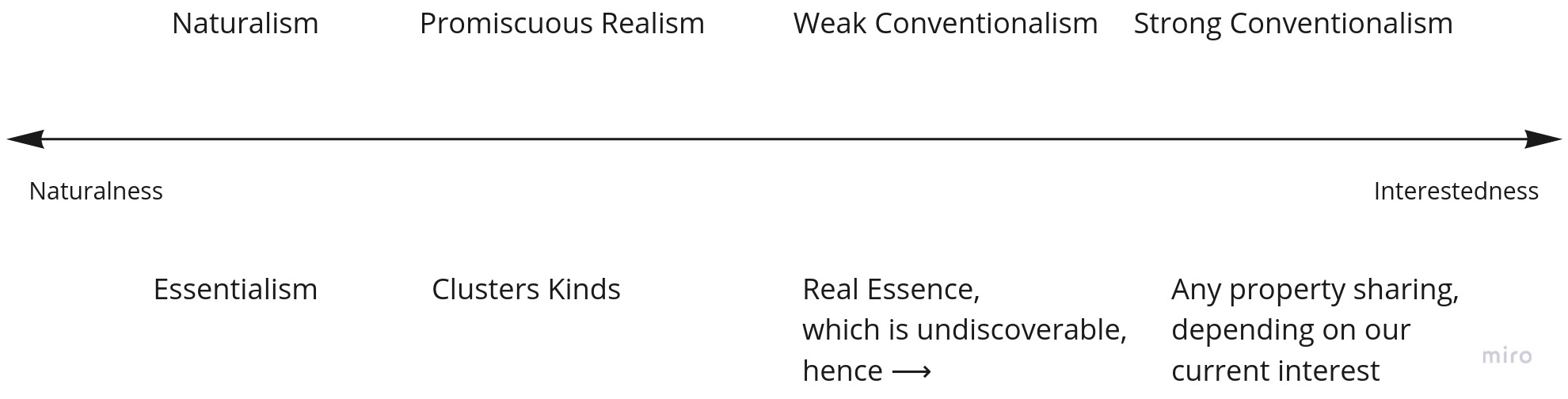

Naturalness vs. Interestedness

All the views above are effectively just different marks on the naturalness-interestedness scale.

This scale reflects a fundamental contention between realists and anti-realists that is akin to a chicken-and-egg problem: are the divisions in the world truly natural, or it’s just us seeing them in a certain way? Is science able to unveil mind-independent natural kinds, or it’s inherently impossible because we’re those who observe and classify?

Monism vs. Pluralism

We can view those views on another plane. How many classification schemes do we have? Is there a single way to classify reality, or there are plenty of them?

Generally, natural classifications tend to accept fewer schemes comparing to conventional ones. On the extreme ends of the scale, strong naturalism claims that there is a single way to classify stuff, and conventionalism allows an infinite amount of them.

What Makes a Category a Natural Kind?

OK, if you’re not an extreme conventionalist rejecting any notion of naturalness, here are the oft considered criteria of whether any given prominent category is a natural kind or not.

Category members share some natural properties

Natural properties are those that are independent of observers. For instance, red apples would have reflected light with a wavelength corresponding to red color even if mankind hadn’t existed. Very often, natural properties are taken to be intrinsic, not extrinsic, but this is arguably not always the case.

Members of a natural kind have some natural properties in common. It’s not a sufficient criterion though: a few people regard all the white things as belonging to a natural kind, after all. But it’s commonly accepted that it’s a necessary one.

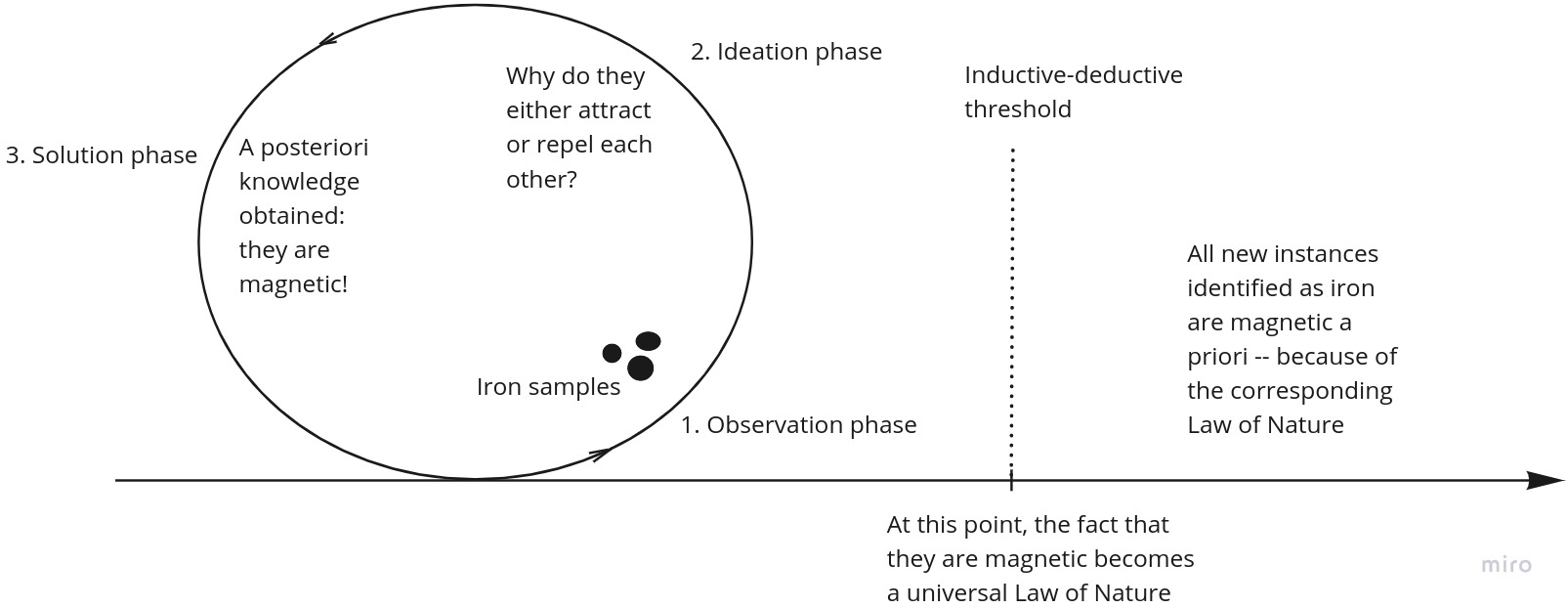

Natural kinds allow inductive inference

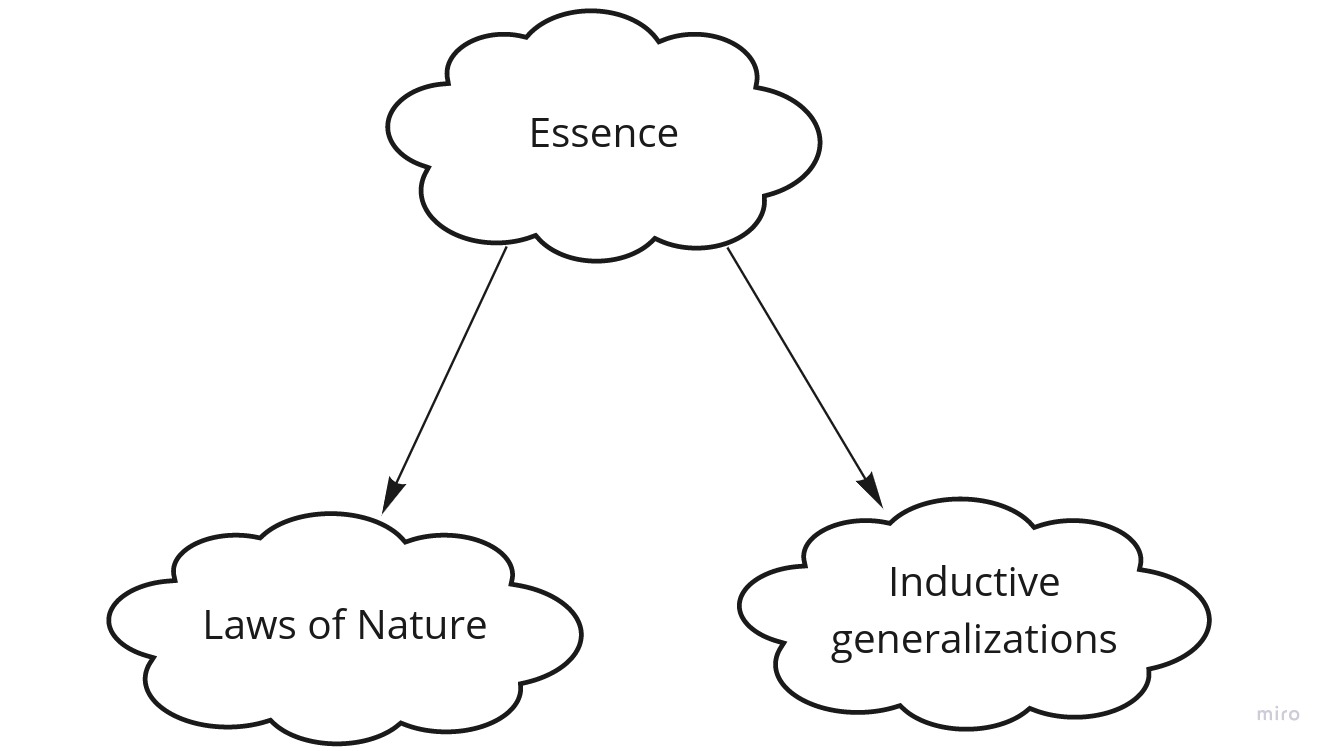

There are actually many forms of inductive reasoning, but here we’re interested in a transition from “All observed as are F” to “All as are F” (in a long-standing metaphysical tradition, a stands for an object, and F stands for its property). This inductive inference can’t fail, because it’s reinforced by the Laws of Nature. Which brings us to…

Natural kinds should participate in the Laws of Nature

When some behavior reaches the bar of being a law of nature, it means that we’re quite sure it never fails, it simply can’t fail. At this point, we no longer look for new evidence to prove that law. Instead of holding a posteriori, it becomes true a priori. At this level of certainty, we can step over inductive reasoning towards deductive one.

More often than not, it takes quite a few feedback loops before some behavior becomes a law. In the image below, a getting-to-know-iron-magnetism loop is depicted.

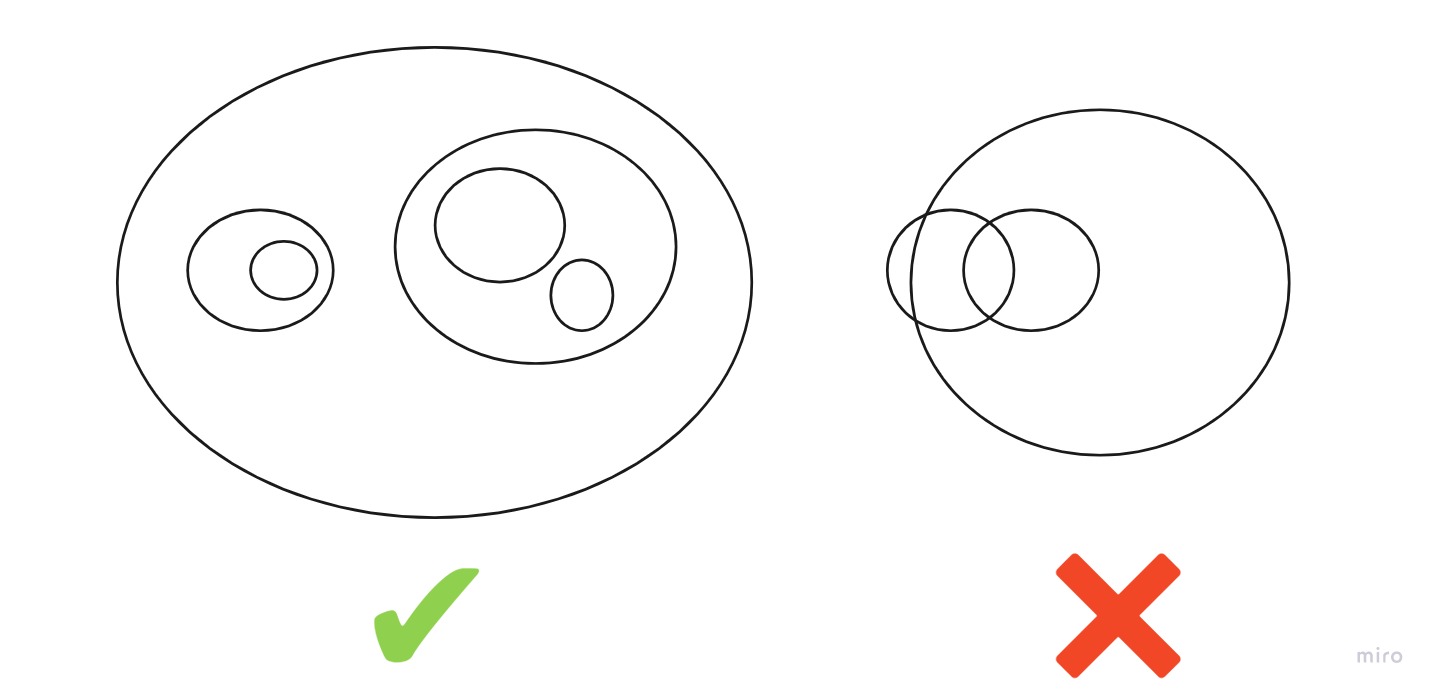

Natural kinds should form a hierarchy with categorically distinct leafs

If any two kinds overlap, then one should be a sub-kind of the other. Besides, borders between two neighboring kinds should be clear and unambiguous; otherwise, it’s us who draw that line. In this case, the concept of a natural kind as a mind-independent category is threatened.

Kinds have made it into our language, and have stuck

Look around. What do you see right now? A computer, a table, some trees, buildings. Something is man-made, something is not. Anyways, those categories are stable enough and have lots of members. That’s the reason why they’ve stuck in our language. As soon as either of those conditions changes, the underlying concept becomes either vague or orphaned - reason enough for the corresponding word first to go out of use, and then out of existence. When was the last time you used the word “pager” by the way?

How are Natural Kinds individuated?

Essentialism

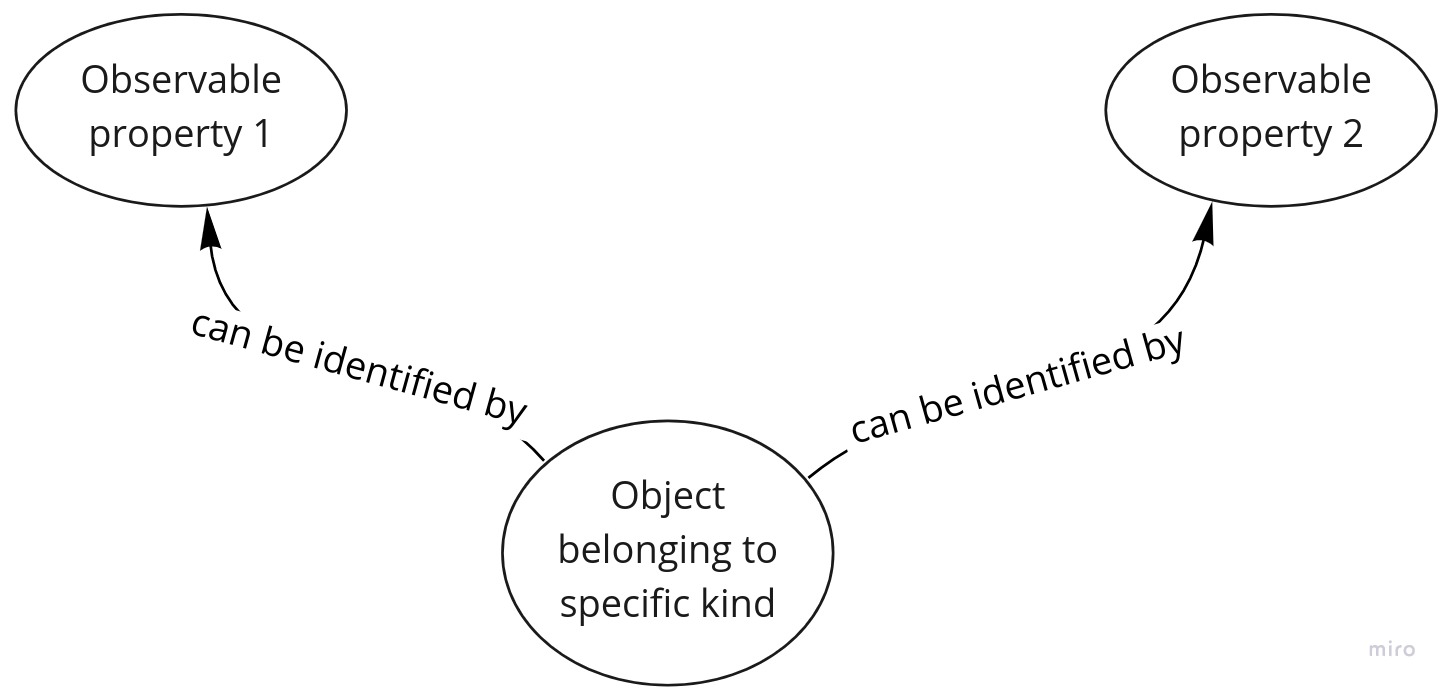

The essence is an object’s property of belonging to a kind it does. That’s what makes an object what it is. For instance, an apple in front of me has the property of being an apple. If it lacked that, it would fail to be an apple. But what exactly makes it an apple? Why is something an apple and some other thing a pear? Essentialism claims that there are specific properties that are shared by specific objects, and those properties make those objects what they are. That is, to belong to a specific kind means to possess specific properties, and those properties are called essential. Essential properties are the only reason why objects are the way they are; they explain all the other properties.

For that reason, an object’s essence can also be articulated as a set of its essential properties.

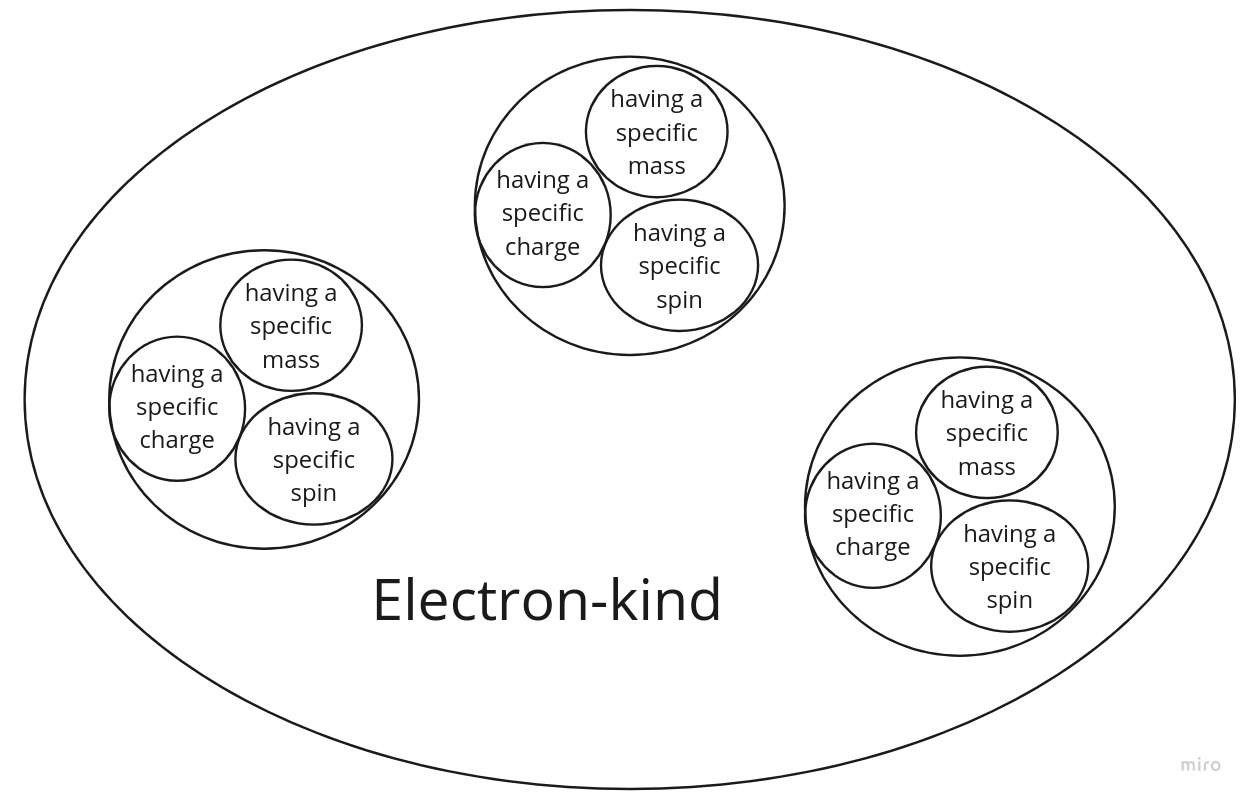

We can claim that electrons have the following properties: having a specific charge, spin, and mass. This combination is exclusively held by electrons, and that’s the core reason why we consider an electron an electron. Those properties are the foundation that we construct our electron-kind upon. Since Natural Kind is effectively a derived concept supervening upon objects’ essential properties, this concept can be projected into kinds: properties making up a kind are called essential for that kind.

All the traits inherent to natural kinds supervene on the essence. It explains all observable properties, allows inductive inference, and is a reason why the corresponding kind participates in the Laws of Nature.

Essentialists are typically monists. This approach results in classifications with clear-cut and non-overlapping categories having clear boundaries. Essentialism can coexist with pluralism, but it states that all the classifications are grounded in a single essence, anyway. For example, we can classify chemical elements by density or stability of isotopes. This classification is arguably no less natural than the one by atomic number, but the reason they look the way they do is rooted in the microstructural properties of chemical elements. The Periodic table just reflects those properties explicitly, where a microstructural property - an atomic number - is a categorization criterion. In the Philosophy of Chemistry, the view postulating that chemical kinds are individuated by microstructural properties is called either Microstructuralism or Microessentialism.

Essentialism and Identity

There is a highly debatable question worth examining: is an object’s essence essential for it? In other words, can an object’s essence change? For an essentialist, an object’s essence is immutable by definition. Once again, the essence is what makes an object what it is. None of the objects can survive essence change. For example, an apple can never become a pear.

There are a couple of paradoxes challenging this view. Neptunium’s decay into plutonium is a classic example. Can we say that some particular plutonium atom previously was neptunium? For an essentialist, chemical elements are paradigmatic examples of natural kinds, and an object belonging to some kind is its essential property. Thus, plutonium atoms can’t become neptunium atoms; they simply can’t survive this transformation. Albeit seeming counterintuitiveness, we can get away with it by not equalizing material constitution with identity. Instead of neptunium’s turning into plutonium, essentialists can say that a new plutonium atom consists of components that were previously parts of some neptunium atom.

Problems

Essentialism faces a problem in biology: it doesn’t embrace mutation. But species evolve and mutate all the time, slowly but surely. Even if there is a specific and unique set of properties inherent to a specific species right now, it likely won’t be the case in a couple of million years.

Cladistic classification is an alternative solution to this problem. I’ve already mentioned it as an example of Promiscuous Realism: the essence of species is having a single mutual ancestor. Arguably, it’s not an intrinsic property, but an extrinsic one - after all, it’s obtained in virtue of the specific ancestor. But typical essentialist view about essential properties is that they are intrinsic. So we have two options here: either remain essentialists and allow essential properties to be extrinsic, or turn to a looser view, such as Cluster Kinds.

Cluster Kind approach

In this view, kinds are individuated by co-instantiated properties. It might look like Essentialism at first, but there are a couple of significant differences.

First off, that property set is not immutable; instead, it has a lifecycle, it’s evolving.

Second, members of a kind are not required to share all of that properties. For instance, at this moment, there is a kind K individuated by properties a, b, c, and d. It’s totally fine that one member might have properties a and b, and some other - properties c and d.

You might wonder whether any arbitrary property set forms a Natural Kind. Not really. There must be a mechanism holding them together, co-instantiated. For example, in biology, homeostasis is such a mechanism. It’s a complex set of physiological processes aiming to keep an organism in a stable state - in other words, alive. There is a huge amount of ways that things can go wrong; homeostasis solves arising issues the best it can. It monitors oxygen levels, body temperature, blood sugar levels, and many more, and adjusts their values to sane levels, when possible. When not, something bad can happen.

It can be regarded as a Realistic view, but it’s too loose for Essentialism: there is no single mandatory and unique property inherent exclusively for the specific kind. There can be multiple ways to categorize stuff in any given domain, but there is no single essence grounding all the classifications. As a result, they tend to be more interest-driven rather than purely natural. Thus, in our naturalness-interestedness scale, it’s closer to Promiscuous Realism.

Any property sharing

The most liberal way to individuate a natural kind is by an arbitrary property possessed by some objects. In this approach, there is a kind of all red things, a kind of all crispy things, a kind of all sweet things, and so on. The way we choose that property is completely up to us. Thus, the kinds are driven exclusively by our interests and aims.

One possible interest area is an object’s function. With this criterion, absolutely different objects can be united by some purpose they all share. For example, if we want to cut something, we can use a pair of scissors, a knife, a piece of paper (ever got cut by it?), a piece of glass, or something else entirely. They all fall under a “something that can cut” functional kind.

Pretty much all of man-made stuff around us is made for a reason. Knifes for cutting, cups for drinking, chairs for sitting. In other words, all of such items can be regarded as belonging to one functional kind or another.

Naturalness vs. Interestedness, revisited

Here is how this scale looks with the different ways to individuate Natural Kinds:

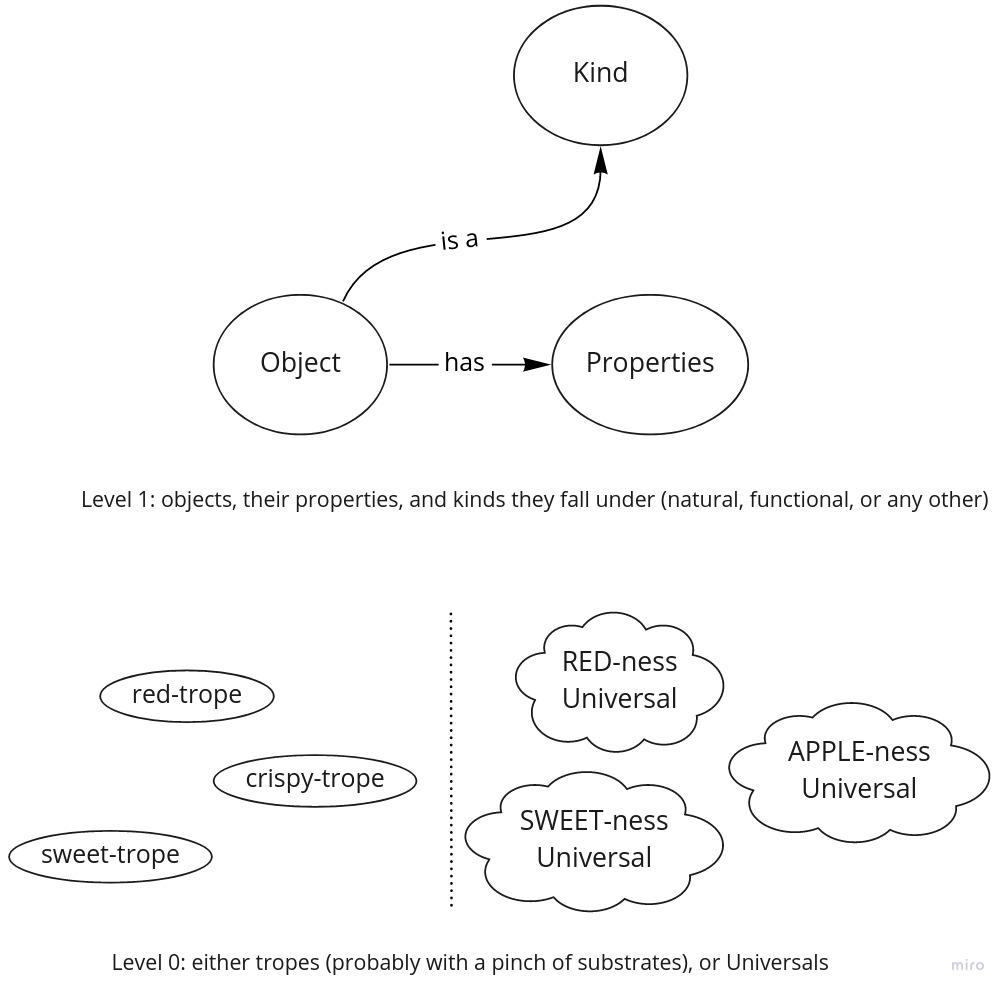

Natural Kind as a Metaphysical Entity

We’ve seen different views on the naturalness of categories we encounter in the world. Naturalism claims that there are genuinely natural, that is, mind-independent ways to carve reality into kinds; Conventionalism claims otherwise, that all divisions are interest-driven. But none of those views says a word about whether those categories represent a distinct metaphysical entity. In other words, those views don’t answer the question of whether such a thing as a kind exists. In a fancier, more metaphysical way of saying, it goes like neither Naturalism nor Conventionalism are ontologically committed.

The Naturalness-interestedness scale is just one way to represent differences between Realism and Anti-realism. Another way is more metaphysical. In this context, Realism and Anti-realism - most prominently, Nominalism - are ontologically committed views. In other words, they have strong opinions about what sort of entities Natural Kinds are. Without further ado, let’s dive right into it.

Realism

There are two realist accounts of Natural Kinds. The first one regards them as the same kind of Universals as the ones grounding properties, while the second - as so-called sui generis, or distinct, entities.

Natural Kinds as Universals

This position, usually referred to as Reductionism, basically boils down (or reduces - hence the name) to Realism about Universals. Here is a short recap.

There are two prominent positions about Universals. The first one, called Platonism, posits them as transcendent entities existing out of space and time. An object has properties in virtue of instantiating corresponding Universals. For example, there is a single RED-ness Universal, and all the red things in the world instantiate it.

The other position is called Immanent Realism. It states that Universals are not out of spacetime, instead they are fully contained in objects. For instance, there are tons of red apples, red hydrants, and red firetrucks; and there is a single RED-ness Universal which is located in a physical world, within all of those red objects.

Whether you’re an essentialist or conventionalist, kinds are some sort of bags with properties. And since we’re talking about Realism here, properties are viewed as Universals, just as Kinds themselves. Thus, Kinds end up being complex Universals; that is, Universals containing other Universals. It’s hard to imagine how this can be possible in a Platonist world though. How comes that RED-ness Universal is part of both APPLE-ness and FIRETRUCK-ness Universal Kinds? Though it fits perfectly with the Immanent Realist worldview. In this account, RED-ness Universal is wholly contained within all the things that APPLE-ness and FIRETRUCK-ness Universals are part of.

One thing to be noted here. It’s not mandatory (oft encountered though) to hold either realistic or anti-realistic positions about everything. One can be an anti-realist about classifications, and a realist about kinds. That is, you might consider that there is no such thing as a mind-independent, natural way to classify stuff, but at the same time, you can view those category entities from a realist position.

Natural Kinds as distinct entities

The second view, notoriously held by E. J. Lowe and Brian Ellis, is that Natural kinds are sui generis entities. That is, they are neither material objects, nor abstract objects, nor sets, nor property Universals, but a completely different thing. Note that I’ve mentioned property Universals, that is, entities like RED-ness and alike. In the current account, kinds actually are a special sort of Universals, called substantial Universals. They have nothing to do with property Universals, they neither reduce to them nor contain them. In metaphysical lingo, this can be articulated as that substantial Universals represent an irreducible ontological category.

Nominalism

In Nominalism, things are pretty much the same as with properties. Objects resembling each other in one way or another can be organized into sets. If multiple objects have a shared property of being an apple, then the resulting set is the corresponding natural kind, the apple-kind.

Ontology so far

Everything we know of grounds on either tropes (probably with substrates, if you’re into a Substratum Theory), or Universals. They are the basic building blocks of reality. This is a level 0 in an image below. One level higher, we have more high-level concepts, namely objects, properties, and kinds.

Further Reading

I’d start with the overview entries, the ones this post heavily relies on: no wonder, they are from SEP and IEP.

Along with kind-object distinction, similar one is type-token.

I’ve mentioned different types of properties that the concept of natural kinds deals with closely; the most prominent are essential and natural ones.

I’ve given several examples from different fields, so if you like digging deeper into special philosophical branches, you can start with Biology, Chemistry, and Physics.

There are some more kinds other than natural and functional ones. For more, check out this paper.