Properties

July 1, 2020 • 28 min read •There are things, and there are ways those things are. Those “ways” are called attributes, traits, characteristics, or properties. Are those properties distinct entities, like my mobile phone or an apple in your refrigerator? Or are they just a way we talk or think of things?

In this humble introduction, we’ll first consider a view that rejects properties as such. After that, we’ll review some reasons for postulating properties and take a glimpse of what they look like. And finally, we’ll discover two major views on what it means to have a property: Realism and Nominalism.

There are no properties as distinct entities

Predicate Nominalism

In this view, there are red apples and red firetrucks, but there is no such distinct thing as redness. Predicate nominalists say that introducing this entity doesn’t bring much at the table. It doesn’t add anything to explanation why an apple is red. With physics, we can explain an apple’s redness with the specific way its peel reflects light. This is apparently because of a specific molecular structure it has. But the question is still open: why does the specific molecular structure reflect light exactly the way it does? In metaphysical lingo, this question typically goes like that: what grounds this behavior? Or, in other words, in virtue of what is this the case? We can say that it’s because an apple possesses a property “being such that it reflects light in a way that most humans perceive it as red”, but this is not very different if we take that an apple is red as a brute fact, simply because we can use a predicate “is red” with a subject “an apple”.

Problems with Predicate Nominalism

First, it seems that Predicate Nominalists try to explain things the other way round. Instead of trying to find out what is it which makes an apple red, they posit quite the opposite: if they can say that it’s red, well, then it’s red. That smells unscientific. Besides, what if there were no humans in the World? Red apples wouldn’t cease to exist, but there would be nothing we could explain their redness with. That the reason why Predicate Nominalism is often referred disparagingly as Ostrich Nominalism.

Besides, the world ontology becomes bloated. Since redness is not shared among all the red apples, we can’t say that some single entity grounds similarity. Instead, each similarity of each red apple pair is metaphysically unique.

That is, the similarity of my red apples is different from the similarity of your red apples. Generally, if there are N apples, there are N × (N - 1) / 2 metaphysically unique dyadic (binary) relations.

The goal of metaphysical ontology is parsimony, and with Predicate Nominalism, we’re way too far from that. Probably introducing properties as distinct entities is not such a bad idea. Let’s see what problems we can solve with them.

OK, let’s say properties exist. Why?

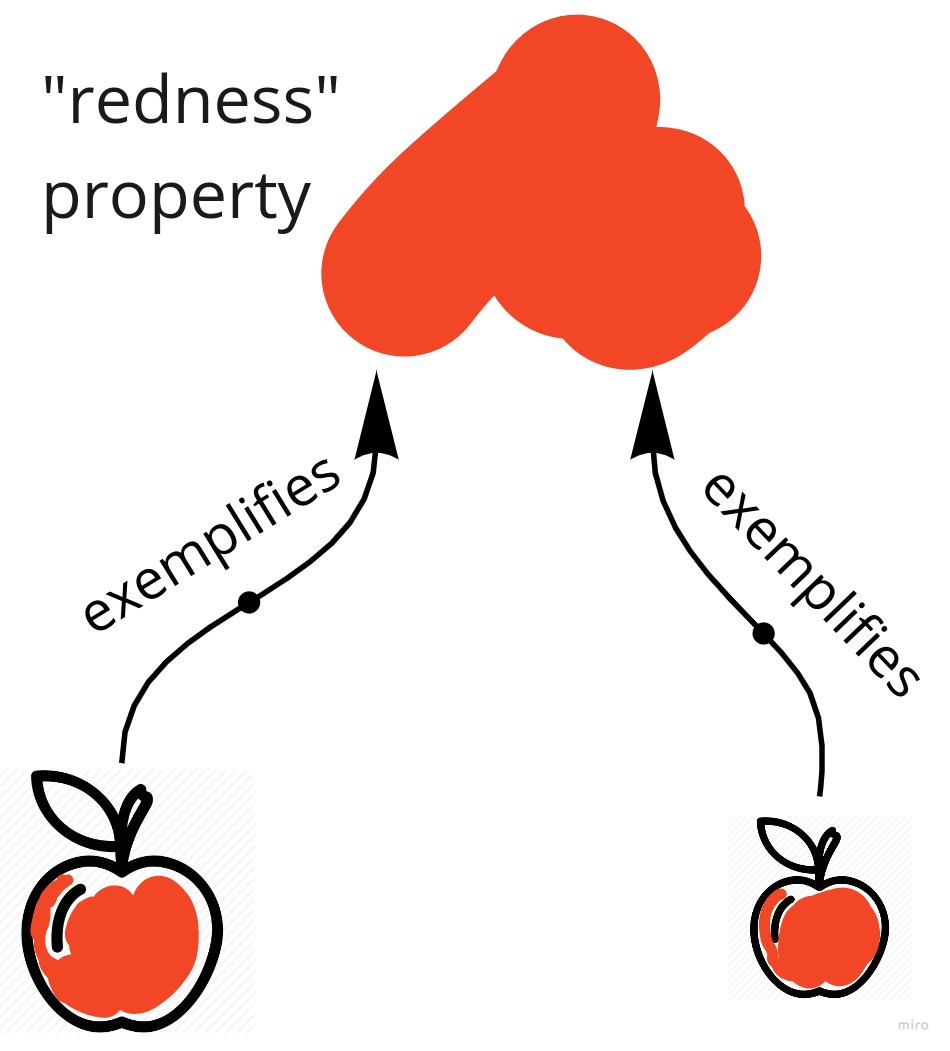

Properties ground similarity

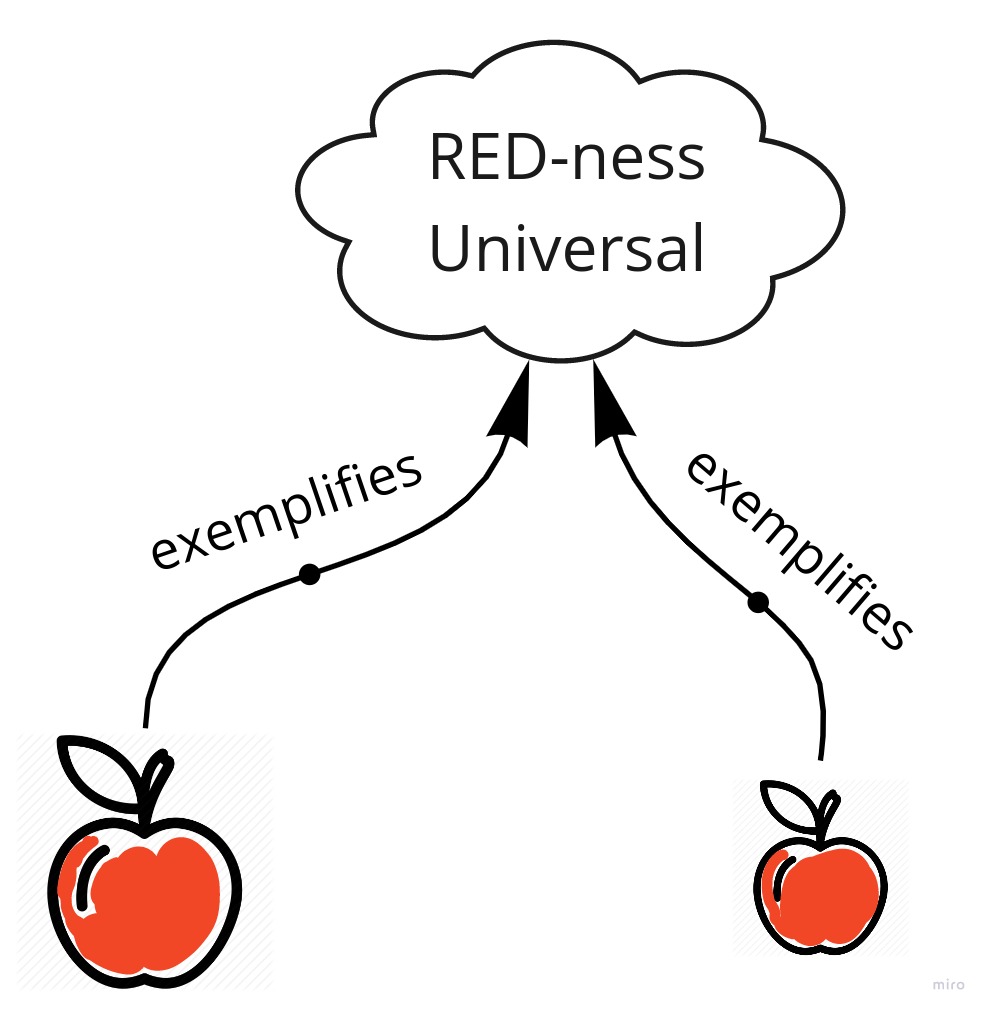

One of the reasons to introduce property as a distinct metaphysical entity results from the previous section. If we introduce a distinct RED-ness entity, we can say that two apples are red in virtue of sharing a single property. Both apples exemplify a single property, that’s why they are similar.

Properties can give a semantic account of a natural language: general terms, predicates, and abstract singular terms

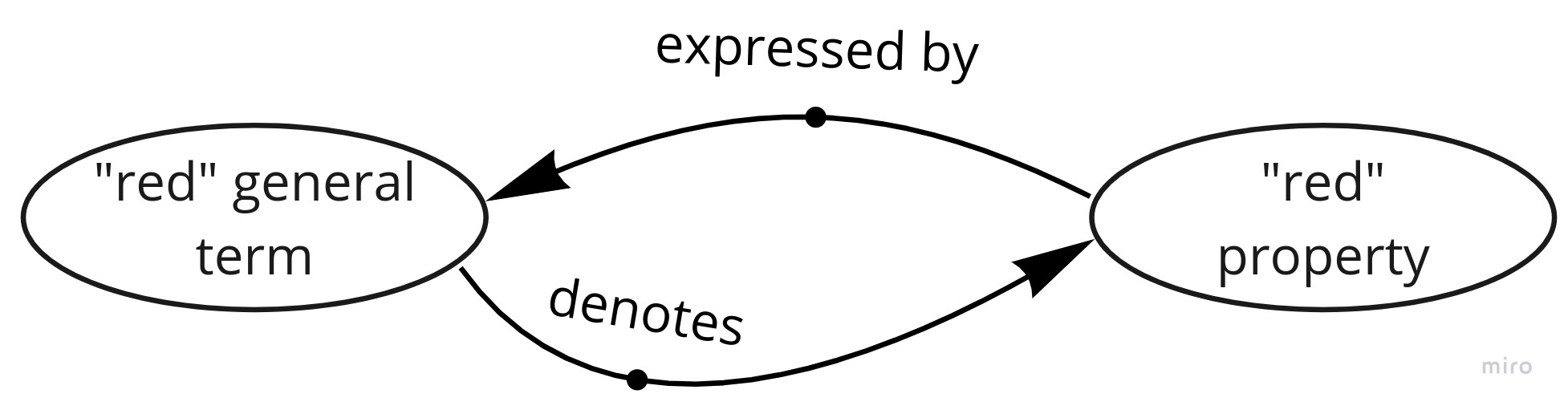

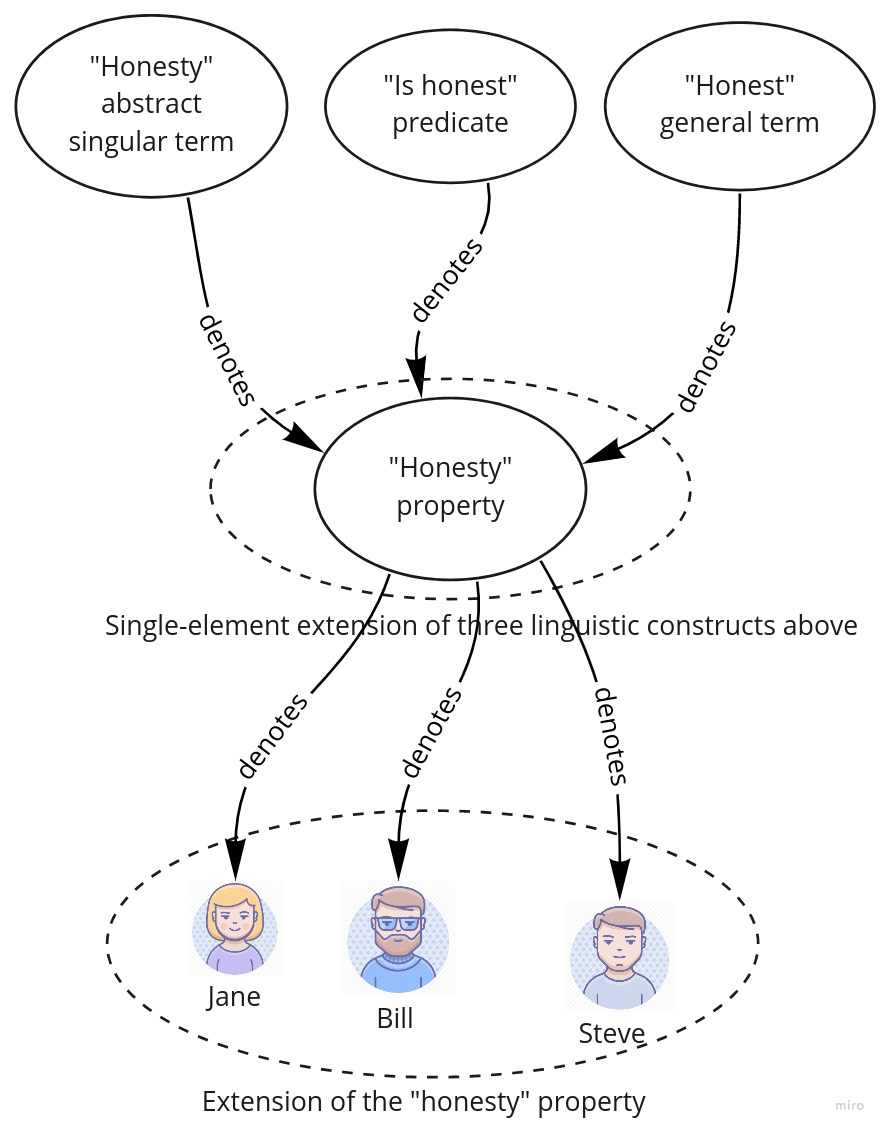

In the philosophy of language, we can explain the literal meaning of a general term by claiming that it expresses a property. For example, we can explain the meaning of “red” with the fact that it expresses, or designates, or denotes, a property “redness”. In other words, “redness” property is a specific thing to which the concept of “red” general term applies.

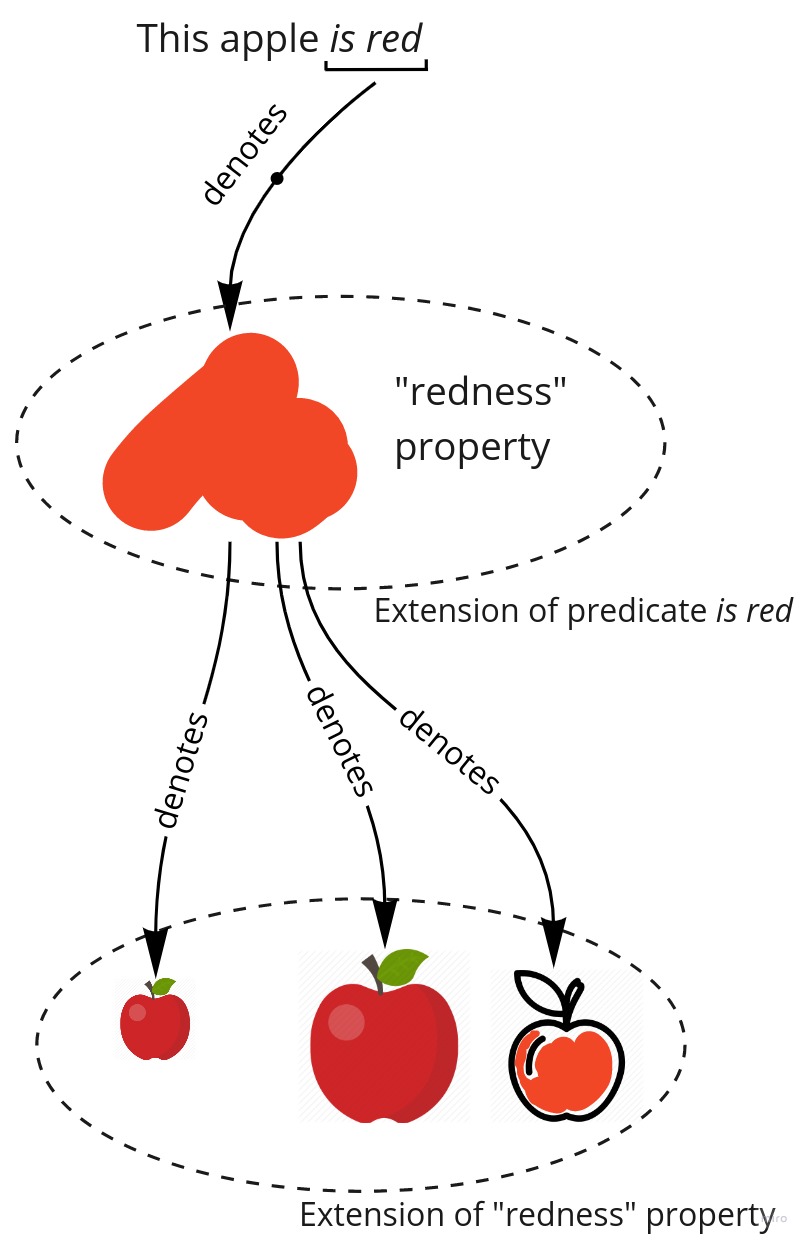

In the same vein, we can introduce a property so that it can be denoted by a predicate. For example, a predicate “is red” from a sentence “This apple is red” denotes a “redness” property. And if this sentence is true, is there anything which that property denotes? Sure, in this case, it can be applied to that apple. In the philosophy of language, they say that it is in the extension of that property, which, in turn, is in the extension of a predicate “is red”. Going in the opposite direction, “redness” property is an intension of all red apples, and “is red” predicate is an intension of a “redness” property.

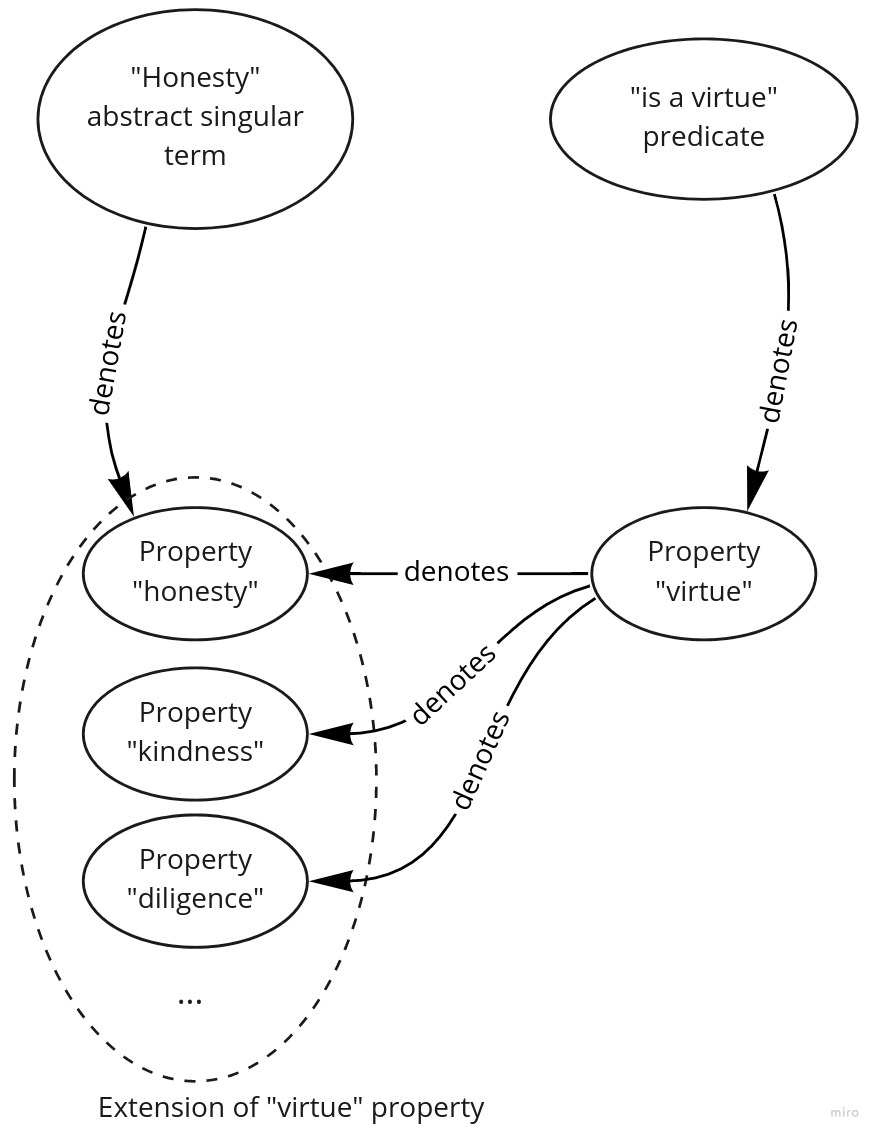

Abstract singular terms, like “honesty” or “redness”, denote the same property that the associated predicate does. In our case, an associated predicate for “honesty” is “is honest”, for “red” it’s “is red”. “Honesty is a virtue” is true when “honesty” denotes a property that is in the extension of the property denoted by a predicate “is a virtue”.

Pretty much any predicate can be nominalized the way I’ve outlined above. So if we accept that properties can give semantic values to predicates, they do the same to abstract singular terms and general terms as a free lunch.

What do properties look like?

There are different accounts of what it is to be a property, and they look differently according to each of those explanations.

If there are two red apples, both of them have the property of “being red”. In this case, metaphysicians say that this property is multiply located, or repeatable: it can inhere in multiple objects, thus be present in different places at the same time. Just like redness is present in many apples at the same time.

Properties can be thought of as being out of space and time. They can’t be identified spatiotemporally. You can’t say where redness was last Tuesday. In this view, a property is called a transcendent entity.

In a natural language, properties often take a form of predicates. Consider the following sentences: This apple is red; I am married to my wife; My sister is in the park; I am sitting; I am tired — predicates are marked italic, and all of them characterize a subject somehow. Hence, they can qualify as referring to properties. It follows that properties are identical if corresponding predicates are identical.

Properties are not perceptible by any of our five senses. Hotness itself is not hot, it’s a cup of coffee which is hot. Redness probably isn’t red either, it’s an apple which is red. In this view, properties are though as causally inert, which means that you can’t interact with them; instead, you can interact with objects possessing them.

Now we know what properties are for, that is what problems they solve, and we have some idea about how they might look like. Next, we can take a closer look at what makes properties identical.

Identity conditions

Once again, there are different views on what are properties, hence there are different views on what it is for properties to be identical.

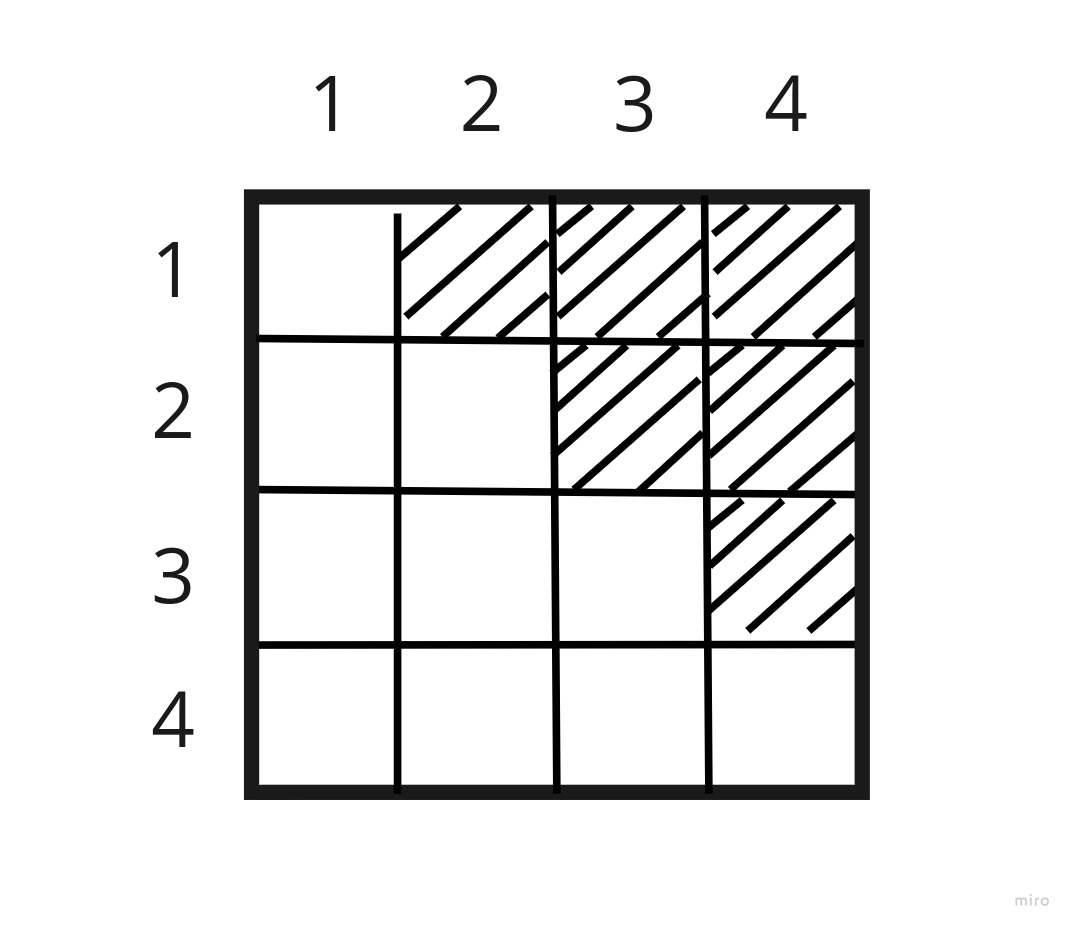

If you take a look at the image where properties give a semantic account to a natural language, probably the most obvious candidate for grounding properties’ identity is their extension. This account is unsurprisingly known as an extensional criterion: if extensions of two properties are the same, then those properties are identical. In other words, there is just one property, not two. But what if each object in the Universe having a property of A, has a property of B either? What makes those properties different? This problem is known as the problem of accidental coextension and will be mentioned further. But now, it seems that a finer-grained approach is required.

We can conclude this account by looking at the same picture. If properties’ extensions coincide, their predicated don’t. Having a heart is distinct from having kidneys because those two correspond to distinct predicates. This approach works out even if all the living organisms having a heart, have kidneys, that is if the extension of those properties is the same. But isn’t it too fine-grained? In this view, being red and sweet is still different from being sweet and red, which doesn’t seem plausible. Since predicates, which are properties’ intensions, are the basis of identity in this account, it’s called a hyperintensional criterion.

Dispositionalism view provides a middle ground between coarse-grained extensional criterion and fine-grained hyperintensional criterion. We can identify a property by a pair of cause and effect. For example, what is it to have a mass of one kilogram? We can identify it as something which grounds the ability of an object possessing this property to accelerate at 1 m/s2 when a force of one Newton is applied.

But what if you pursue a categorical account? For you, properties are not what something could be, but what something is. Thus, properties can’t be identified by causal relations. Instead, they should possess some unique identifier which makes a property just be that property. This intrinsic qualitative nature is called quiddity. It’s sort of primitive such-and-such-ness. To be honest, when I first encountered this concept, I thought that it was too much for me. It’s too mysterious, and even now, I have difficulties conjuring it up. How can we even know them? Philosophically speaking, quiddities have serious epistemic challenges.

OK, let’s move on and take a look at properties’ population.

How many properties are there?

There are four views on this question. The first one, Minimalism, implies that there are very few fundamental properties. In a well-established metaphysical terminology, they say that the realm of properties is sparse. The most prominent candidates for such properties are the ones from physics, like spin and charge of quarks, opposing to being red and being sweet. We can employ two strategies to deal with the latter. The first option is to accept their existence, but in this case, we must claim that such properties are not fundamental and supervene on those which are. To put it differently, non-fundamental properties are ontologically determined by the fundamental ones. The second option is to reject their existence, claiming that they are not distinct metaphysical entities, but linguistic or conceptual ones.

The second view is to accept that all the possible properties exist, both fundamental and non-fundamental: consisting of molecules, having a mass, having a mass of 7 grammes, having a mass of 96 kilogrammes, etc. Some accounts endorse even impossible properties, like being a square circle or being bitten by a dinosaur last Thursday. This account is called Maximalism, where, as metaphysicians say, properties constitute an abundant realm and thus follow a principle of plenitude. It’s ontologically bloated indeed, but it’s more explanatory powerful: there is a property for any possible predicate. Thus, all predicates have a semantic value. Besides, the Maximalist account is epistemically controversial. On the one hand, natural properties like being red are easy to find — as easy as identifying a predicate in a sentence, actually. On the other, non-existent properties like being bitten by a dinosaur last Thursday can’t be ever discovered by definition.

It’s tempting to take a middle ground view, and that’s what Centrism aims at. But a criterion of which properties are allowed and which are not is surprisingly hard to formulate. There are many positions, and there is no consensus.

The fourth view called Dualism postulates that we can choose granularity depending on the task at hand. If we’re talking about linguistics and semantics, we can take fine-grained properties denoted by predicates. In Dualism, they are called type I properties. If we’re up to naturalistic ontology, our properties can be coarser-grained: property of having a horn and hooves is identical to having hooves and a horn. They are called type II properties. By far, it seems to be the most viable option.

Now as we already know how properties look like, how they can be individuated, and how many of them there are, we can consider different classifications of properties.

What properties are there?

I’ll give just a brief account of each classification, skipping the problem parts. You can find links to more in-depth articles at the end of this post.

Intrinsic and extrinsic properties

There is an apple in front of me. It’s red, sweet, and weights about 200 grams. Besides, it’s lying on the edge of a table, has traveled from China, and was bought at the corner shop. Both statements represent an apple’s properties, but they seem different. Properties from the former statement obtain because of an apple itself, because of its nature, independent of anything else. That apple would be red, sweet, and weight about 200 grams even if nothing except that apple existed. But properties from the latter exist because of something else: other objects and relations with them. An apple lying on the edge of a table is because of a table and an apple holding a specific relation with it; the property of having traveled from China seems to exist because of China’s existence and an apple’s relation to it; and so does a property of having bought at the corner shop. The first kind of properties is called intrinsic, the second one is extrinsic, or relational.

Accidental and essential properties

I have a property of being a human. I can’t lack this property. If I had lacked it though, an object I refer to as “I” wouldn’t exist. On the other hand, right now I’m wearing a tee-shirt with Deadpool. If I had put another tee-shirt on this morning, I’d stay the same person.

It seems that there are properties that an object must have to reinforce its existence. Those properties are called essential. Some philosophical accounts claim that a bunch of essential properties form a distinct metaphysical entity called natural kind. It is a type of object; some philosophers claim that it is a property itself. Consider the following properties: having a charge of −1.6×10−19 C, having a mass of 9.1×10−31 kg, and having a spin of 1/2. Does it remind you of anything? Correct, those are properties of an electron. So together they form a concept “electron”. So if we find some object which has those properties, we can say that it is an electron. It can have other properties as well, and they can very well be different from other electrons’ ones. But those properties are not essential to electron, they don’t make electron what it is. They are just accidental. But if some object lacks only one of the properties essential to electron, then it is not an electron. Natural kinds are abstractions in this regard: they only keep the essential and sweep away everything else.

Determinable and determinate properties

Property of being honest is a specific case of having a virtue. Property of being red is a specific case of being coloured. The former are called determinate properties, while the latter are determinable. The same property can be a determinate in one context, and determinable in another. For example, being red is determinable relative to being crimson; but it’s determinate relative to being coloured. Usually, all the determinate properties exclude each other. Just like a natural kind is a sum of all distinct objects falling under it, determinable property is, roughly, a disjunction of all determinate ones.

Determinate properties seem to be more fundamental; they make determinable property to be what it is. Hence, in the Minimalism account, only determinate properties exist; and determinables reduce to determinate. Determinable ones are sort of useful fictions that we humans use colloquially. Strict hierarchy in a perfectly determinate world without any metaphysical vagueness is appealing indeed.

In the Maximalism account, the entire rich stock of all kinds of properties exists.

Relations

Extrinsic properties seem to obtain in virtue of relation. For example, an apple lying on the edge of a table is a relational property which holds in virtue of a relation between an apple and that table. Some say that those relations are itself properties, some say that it’s a means for instantiating properties. It might (and I bet it does) sound elusive right now. Don’t worry, I’ll go in more detail about it a bit later.

Categorical Properties and Causal Powers

I’ve already covered this topic in greater detail, so I’ll just outline the basics here.

There are ways objects are: some object is triangular-shaped, has a side equal to 85 cm, is red, and lies on the table. Those kinds of properties are called categorical.

Likewise, there are ways objects could be. Those ways manifest under certain circumstances, and those circumstances can never happen. That vase is fragile — it means, it shatters if thrown on the floor. In this case, a property of being fragile confers a power of shattering on a vase. Sometimes, those powers are the only ways we can comprehend properties. Another example is a charge of an electron: the only way we can know it is the way it interacts with other charged objects. Does it repel or attract other electrons? And what about protons? This view of properties is called dispositional. The overall approach when objects’ properties are defined by the way they interact with other objects is known as Structuralism.

Some philosophers claim that there are only categorical properties, some say otherwise, that there are only dispositional ones. Others try to find some middle ground: either by claiming that some properties are categorical and some dispositional, or arguing that all the properties are both categorical and dispositional.

OK, now it’s time to dive a bit deeper and consider what properties are. There are two general views on that subject: Realism and Nominalism. Put your seat belt on: dark, dense metaphysics ahead.

Realism

Generally, realism is a view that accepts that Universals exist. Part of realists agrees that they ground objects’ character. But the concept of Universal means different things in different Realism branches. Here, I’ll consider two of them: Platonism and Immanent Realism. The first one has its roots in Plato’s views which are now known as Extreme Realism, and the second one traces back to Aristotle’s views, which collectively go under Strong Realism label.

Platonism

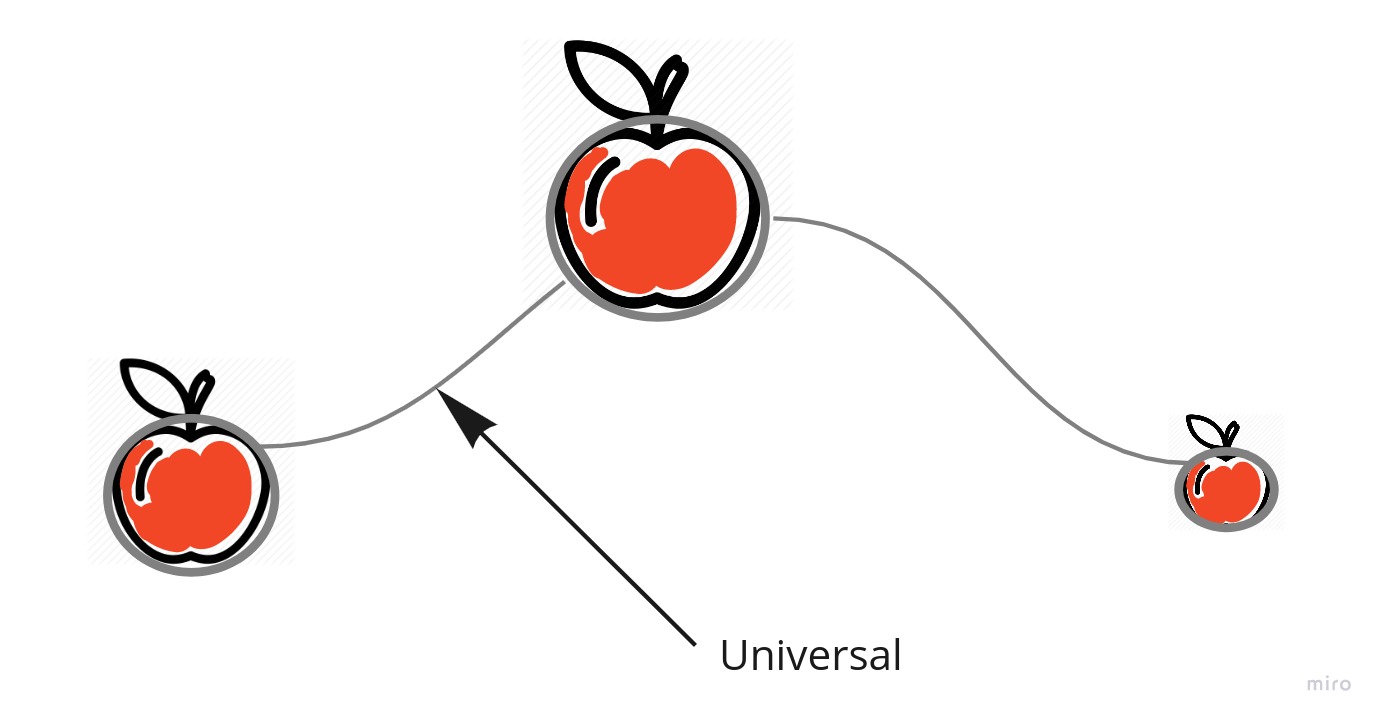

Platonism is arguably a contemporary version of Plato’s views, though it’s not completely clear what Plato meant when described his views. We can say that both views postulate the existence of a transcendent entity which is out of space and time: you can’t see it, you can’t touch it, you can’t interact with it in any way (metaphysical way of saying it is that they are causally inert). This entity is called a Universal.

Plato has described it as an “idea”, or a “perfect Form” of something. His train of thought has led him to what we now know as a “One over Many argument”. It goes like the following. Say I have a red apple, a red firetruck, and a red rose. These objects are clearly similar in a certain way. Hence they have something in common, and the “redness” property seems to be exactly that. Thus we can conclude that redness exists. But despite this example, it seems that both Platonists and Extreme Realists tend to prefer Universals like APPLE-ness, instead of RED-ness, SWEET-ness, and HAVING_WEIGHT_OF_ABOUT_250_GRAMS.

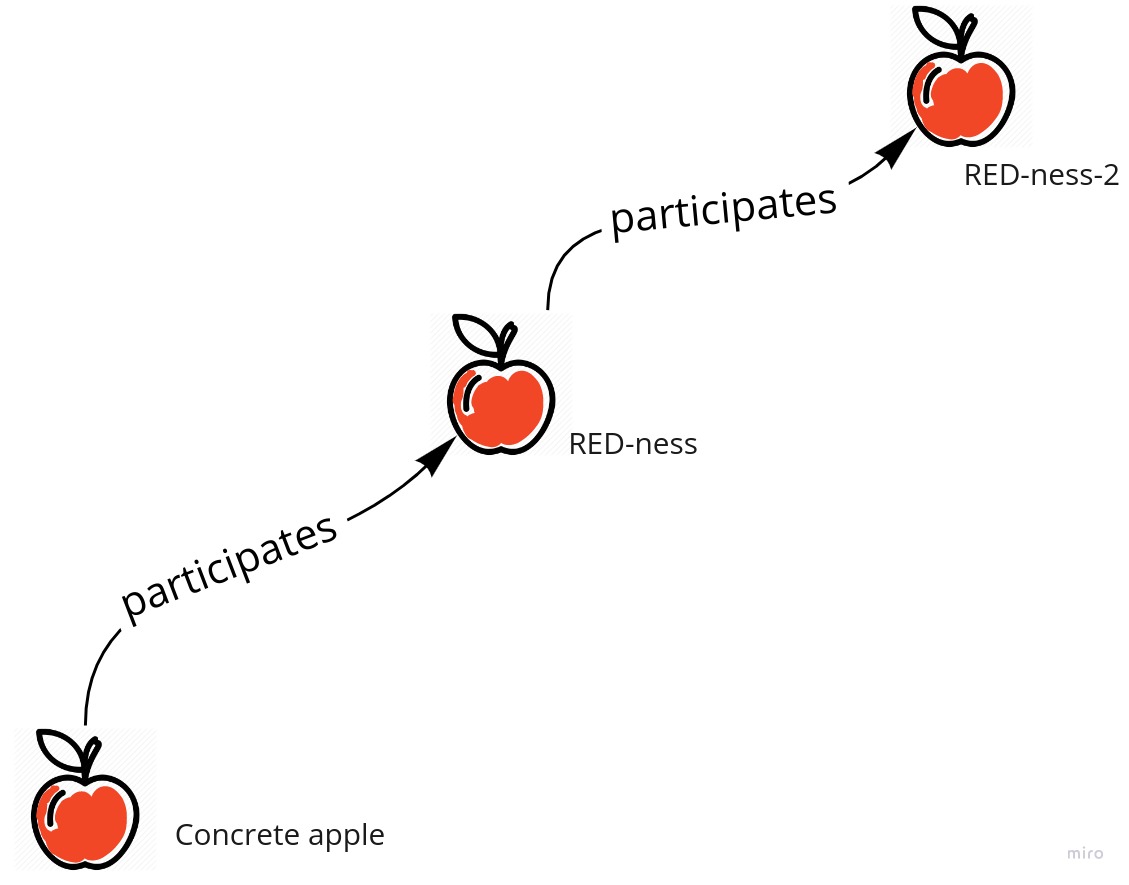

The way objects possess properties seems to differentiate Platonism from Extreme Realism. Plato thought that objects participate in Universals, and Platonists consider that this way of thinking implies a causal relation between an object and a Universal. They regard Plato’s view of Universals such that they are responsible for an object having its nature. In practical terms, it means that the APPLE-ness Universal is an apple itself, or RED-ness Universal is itself red. Contemporary Platonist’s view is that objects exemplify, or instantiate, Universals. This perspective implies that Universals are in no way responsible for an object to have its character; instead, it is a fundamental, primitive, unanalyzable exemplification relation which is in charge. Platonism, unlike Plato’s Extreme Realism, asserts that the APPLE-ness Universal is not an apple, and the RED-ness Universal is not red. Thus, Platonists answer the question “Why is this apple red?” not the way Extreme Realists do. Extreme Realists’ answer would be “Because it participates in the RED-ness Universal, or Form, which is red itself”, and Platonists’ answer goes like “This apple is red because it exemplifies (or, is an example of) the RED-ness Universal”.

In both views, a red apple itself doesn’t possess any unique distinct entity accounting for its color. A perfect Form and participation relation is all there is in Extreme Realism, and a Universal and exemplification relation is all there is in Platonism.

Objections

Precaution

We all have some beliefs. For example, talking about software development, I believe that the way you approach domain decomposition in some project, is way more important than the programming language you use. Why? Because, in my opinion, this path at least has a chance to make further maintenance efforts a bit less of a nightmare. Why? Because it makes program code aligned with abstractions operated upon in business realm, and, in turn, leads to a palatable fact that we, developers, don’t have an unnecessary cognitive load when translating real-life user stories into code. The absence of this cognitive barrier is what distinguishes easy-to-maintain code and hard-to-maintain code. Why? I don’t know. I just believe this is so.

Arguing against beliefs is not easy; arguing against fundamental beliefs is almost impossible. Those basic beliefs are by definition the very first turtle holding everyone else. There is no logical justification for holding them. You take some belief as fundamental at some point in your life, probably because your overall experience has led to believing so. And no one seems to be willing to change them. Bad news: this type of argument is the only one making sense. Good news: there are some other, less demanding ways.

One of them goes like the following. First, as an objector, take your beliefs as superior to anyone else’s. Then, point at someone else’s belief which is based on something you don’t believe to be true. Finally, claim that it’s wrong because it’s not based on your beliefs. Voilà, congratulations: argument won.

Sadly, you can see such kinds of arguments in metaphysics realm. Some of them are claimed by authoritative sources, thus becoming famous enough to be aware of. And some of them are represented here in this post. I won’t explicitly mark them. Try to figure out yourself. Ask yourself questions. Find the answers. At the end of the day, you’ll understand way more than when you just started.

Bradley’s regress

It’s an umbrella term for a bunch of related problems. All of them boil down to the fact that any appeal to relation to relate an object with a property will require further relation. Thus, an argument ends up in a vicious circle.

The first problem from this series was postulated by Plato as an objection to his own view, Extreme Realism. It went like the following. If an apple participates in a RED-ness Universal, then the RED-ness Universal is itself red — because of the way Plato perceived a participation relation. If so, there must be another Universal, RED-ness-2, which grounds the redness of the RED-ness Universal. And so on. This regress is vicious.

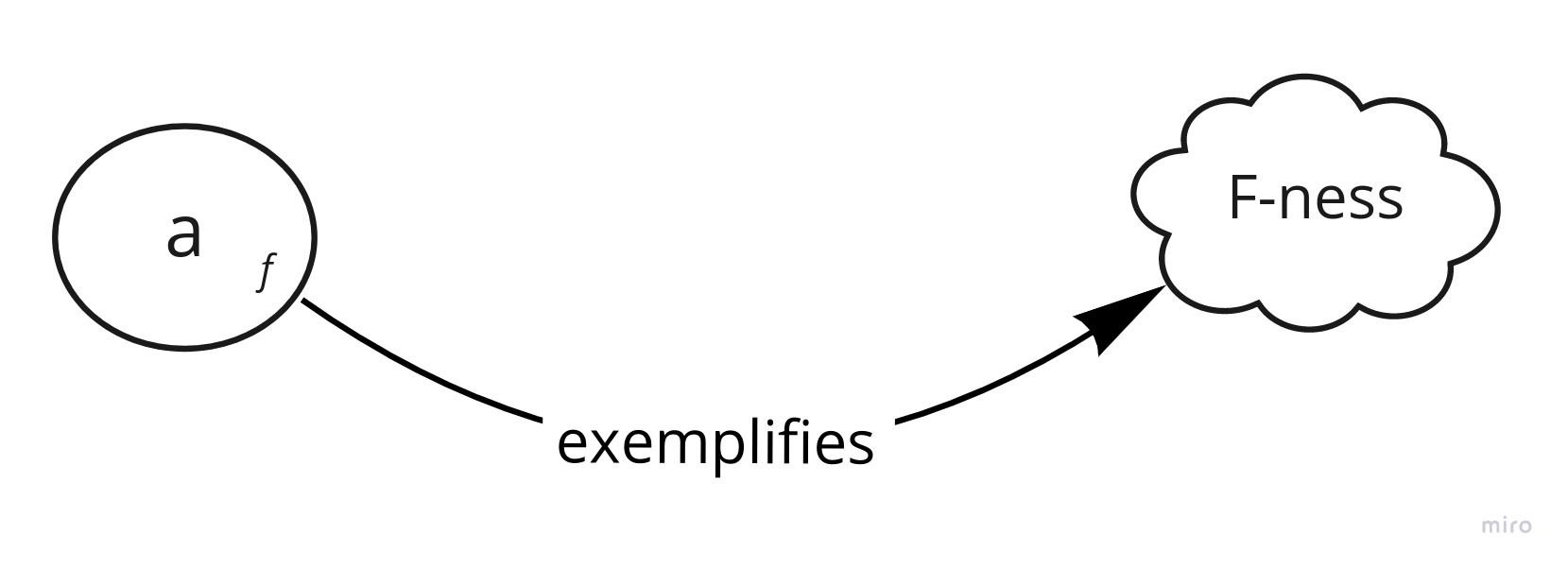

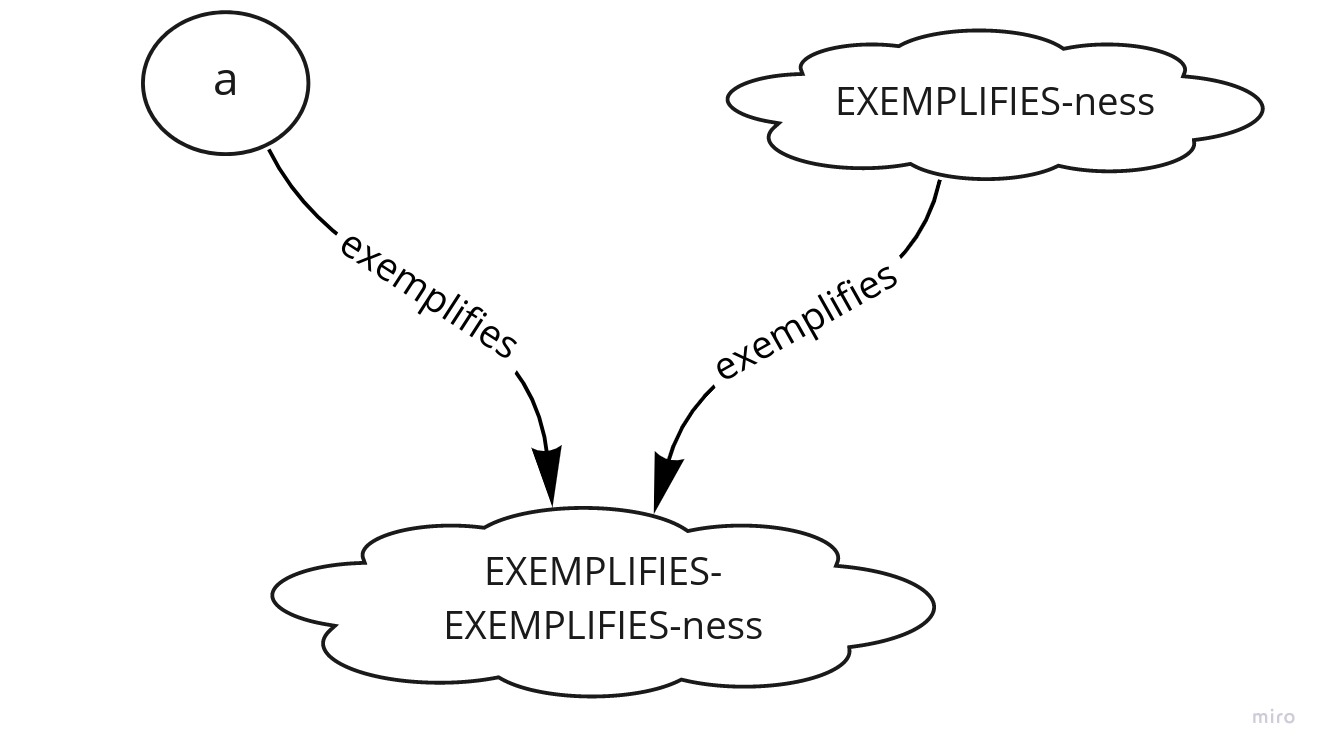

The contemporary version of Bradley’s regress concerns any kind of relation. Let’s say that an object a is f, or a exemplifies F-ness.

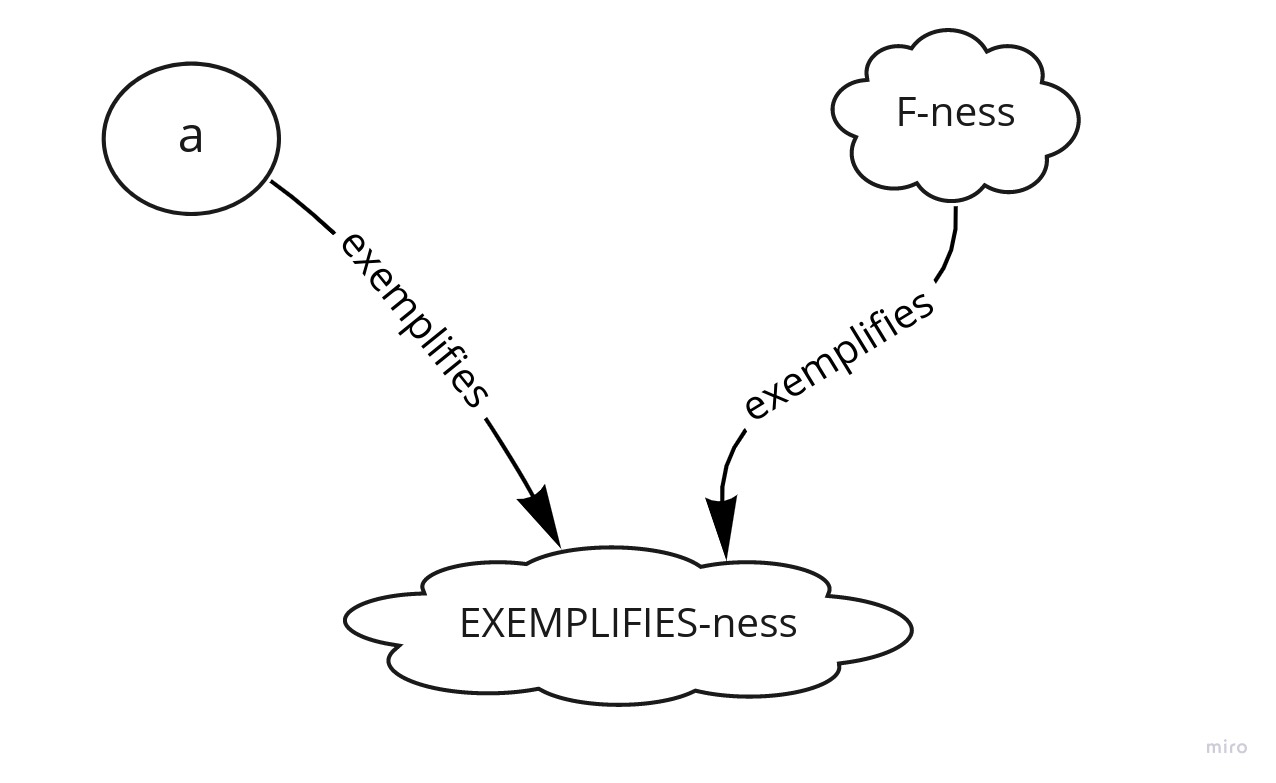

Take a more close look at the last sentence, “a exemplifies F-ness”. There is a subject, “a”, referring to an object a, and a predicate “exemplifies F-ness”, which, as mentioned earlier, denotes a property. A property which is inherited by more than one thing is called a relation, or a polyadic property. In our case, exemplifies is a dyadic property, since it requires two relata: an object a and a Universal F-ness. Let’s call it EXEMPLIFIES-ness, which is, according to Realism, a Universal. Thus, this Universal must be exemplified: “a exemplifies “exemplifies F-ness””.

Since a exemplifies EXEMPLIFIES-ness is a relational property, there must be another Universal exemplified by both a and EXEMPLIFIES-ness: EXEMPLIFIES-EXEMPLIFIES-ness.

See the pattern? We’re in a vicious circle again.

Multiple attempts have been made to avoid this uncomfortable regress. They are either implausible, or boil down to treating instantiation relation as a brute fact.

Paradox of self-instantiation -a branch of Russel’s paradox

This paradox shows that properties can’t be expressed by predicates in every case. Let’s consider it in a bit greater detail.

First, it seems that some properties can exemplify other properties. A vivid example is that any property seems to exemplify a “being a property” property. Hence, properties are self-instantiating. Second, for any property Q there is a negative property, non-Q. Thus, there is a property of “not instantiating itself”, let’s call it NII. Let’s call the opposite property, “instantiating itself”, II.

The paradox is that NII is logically impossible. If NII doesn’t instantiate itself, then it instantiates “not instantiating itself”, which we called NII. Hence, NII instantiates NII, that is, NII instantiates itself - a contradiction to our initial assumption. OK, let’s assume that NII instantiates itself. This means that NII instantiates a property of “instantiating itself”. This, in turn, means that NII doesn’t instantiate a property of “not instantiating itself”, or, put another way, NII doesn’t instantiate NII. Thus we conclude that NII doesn’t instantiate itself, which is a contradiction to our prior assumption, that NII instantiates itself.

There are two major ways to resolve this paradox. The first one is to reject the assumption that if an object a doesn’t instantiate property F, then it instantiates non-F. The second boils down to a properties hierarchy. Objects instantiate first-order properties. They, in turn, instantiate second-order properties. Thus, there is no such thing as self-instantiating property.

Epistemological concern, or strangeness objection

Predicate Nominalists don’t find Realism compelling: they reject the conclusion of “One over Many” argument in particular and deny the existence of Universals in general. As I outlined at the beginning of this post, they show that they lack explanatory power. Besides, Universals have known epistemological concerns indeed, since Platonistic Universals are causally inert; how can we get to know them then? How can we even think of them? What are they, anyway? To say the least, they’re quite strange creatures. So strange that they engage the minds of philosophers for about two and a half thousand years; this problem even has a special name: it’s commonly referred to as the Problem of Universals.

But they are about the World’s ontology. That is, Platonism as part of Metaphysics, tries to discover what there is, what the World consists of, and why, instead of how we can get to know it. Four hundred years ago Giordano Bruno was executed for believing that the Earth was not a center of the Universe. Higgs boson was introduced in a theory of why particles have mass in 1964, but it was first detected only in 2012. Right now, dear reader, you might wonder why you’re still reading this nonsense about Universals. We can just wait though.

Immanent Realism

This position has its roots in Aristotle’s views and is also known as Strong Realism. It posits that Universals exist, but they are not transcendent entities existing outside space and time. Instead, Universals exist in the physical world. For example, in this view, redness exists in a red apple as its part. After all, if you look at an apple, you’ll see that it’s red. If you accept redness as such, it seems plausible that it’s part of an apple, which is right in front of you, in spacetime. Consequently, you can conclude that its redness, in turn, is in spacetime as well, and that it’s not a transcendent entity that Platonists talk about.

Immanent, or Strong, Realist doesn’t have to introduce an exemplification relation. There are just objects and properties (which are Universals), and those Universals are not instantiated; instead, they inhere in physical objects, and they can’t exist uninstantiated. For some, this sort of Universals might seem less strange than transcendent ones.

Universals in both versions are still multiply located, they still ground similarity and give a semantic account to a natural language.

Objections

Just like Platonism Universals, being abstract entities, are strange for Immanent Realists, the fact that one thing exists in several places at the same time is strange for Platonists. It seems that it’s a matter of initial beliefs and worldview, so this one doesn’t count as an objective rejoinder.

What exactly is property possession? In Platonism, it’s an exemplification relation. What is it in Immanent Realism? Most of the metaphysicians endorsing this view wouldn’t say that there are any relations in property possession since they want to escape Bradley’s Regress. Instead, they say that an object and a Universal are just linked together somehow in a non-relational way. Actually, the same can be said of Platonists, who mostly accept an instantiation relation as unanalyzable.

Nominalism

Nominalism about properties claims that Universals don’t exist. I’ve already mentioned Predication Nominalism - a version of Nominalism taken to the extremes, where objects’ character is ungrounded - unless you consider a fact that a predicate can be applied to a subject as grounding.

Resemblance Nominalism

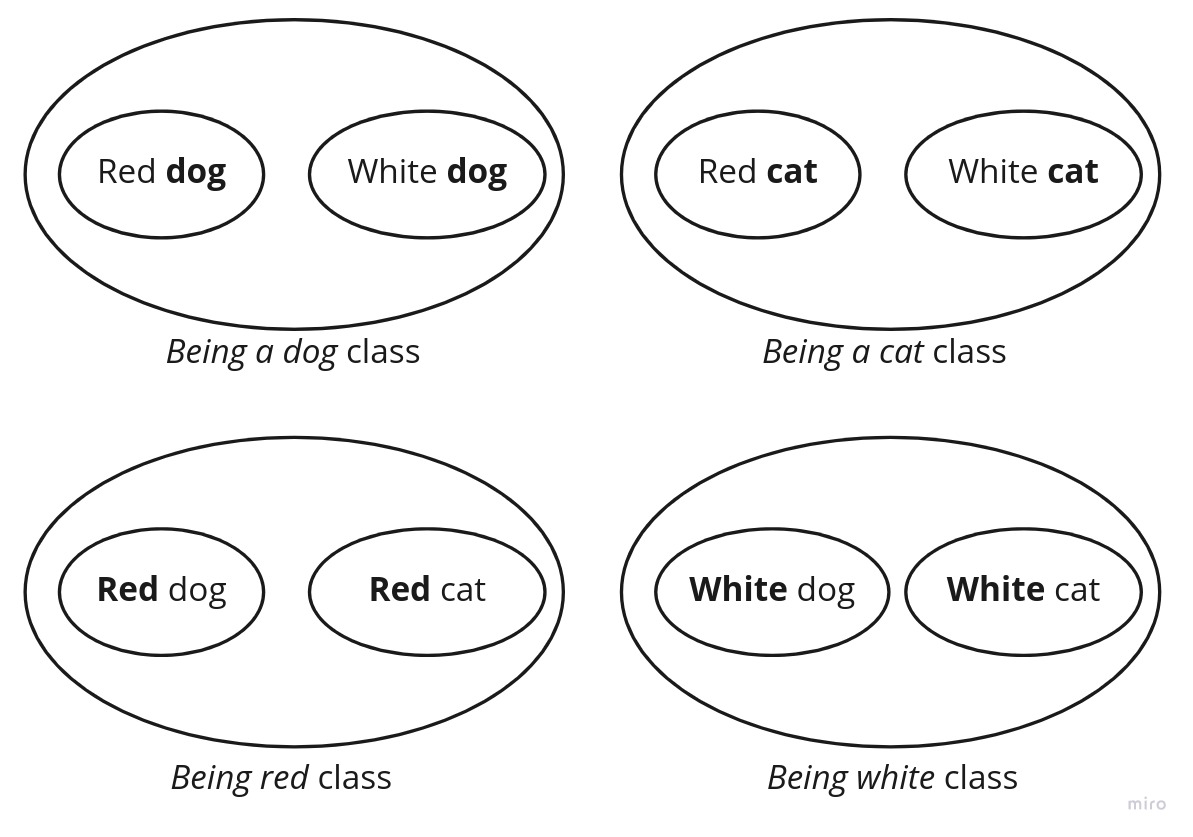

In this version of Nominalism, resemblance relations are fundamental. That is, the certain way that red apples, red firetrucks, and red roses resemble grounds the fact that all three are red. In other words, apples are red in virtue of resemblance relation held between all red things. So, answering the question “What are shareable properties in Resemblance Nominalism?”, we can reply that they are classes, or sets, of objects that resemble. But, once again, those classes are secondary; resemblance relations are fundamental.

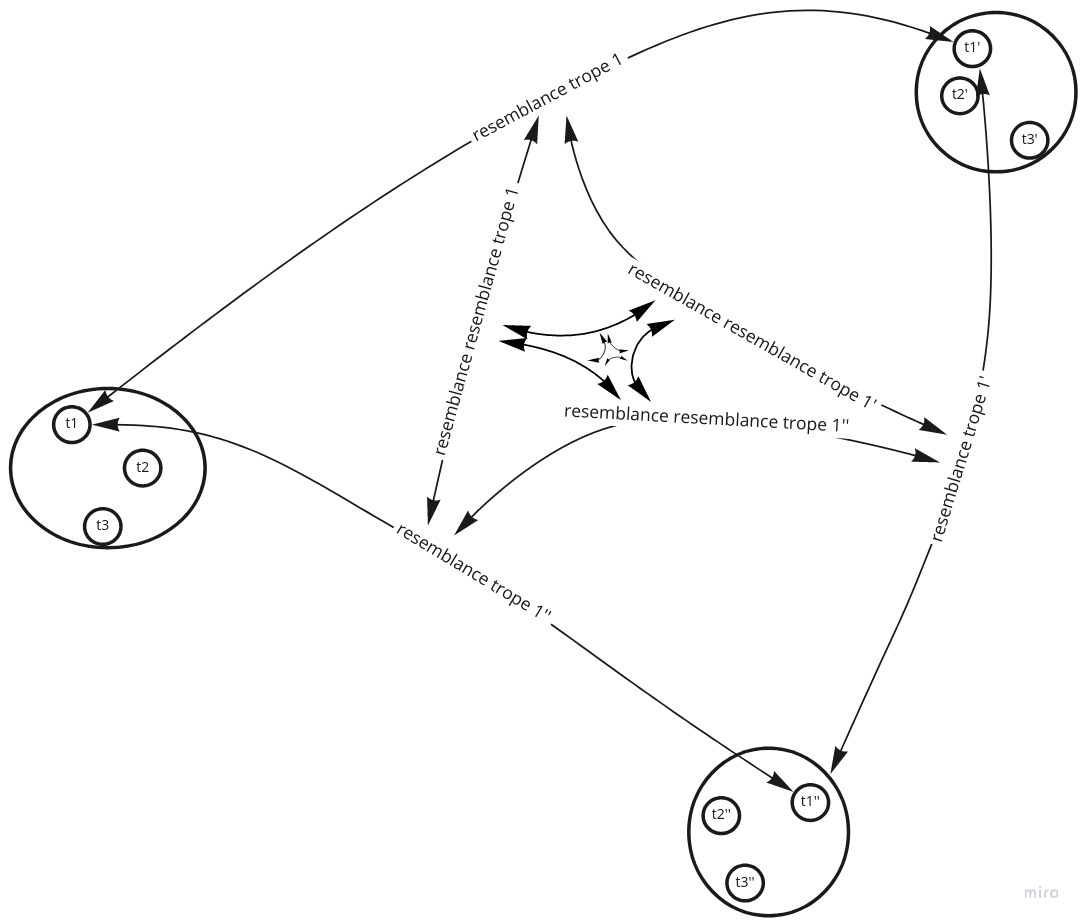

But how to discover those resemblance relations? Look for the ways different objects resemble more or differently. Take a look at the image below:

In an image above, red dog and white dog resemble each other differently than anything else, hence they form resemblance class. So do a red cat and a white cat. As a result, we can refer to those classes as properties “being a dog” and “being a cat”, which, once again, derive from the particular way some objects resemble. On the other hand, a red dog and a red cat resemble each other differently too, as well as a white dog and a white cat. Thus we have two more classes which denote properties that we can call as “being red” and “being white”.

One thing to be noted here. Resemblance relations in this version of Nominalism are not full-blown metaphysical relations which actually exist. When Resemblance Nominalist says that a resembles b, there are not three things in her ontology: a, b, and resemblance relation. There are only two of them: a and b. A resemblance relation is grounded in the fact that we can say that a and b resemble, which makes this version of Nominalism resemble (pun intended!) Predicate Nominalism. But in the latter, each resemblance is unique, which makes the ontology bloated. Besides, in Resemblance Nominalism, we can refer to resemblance classes as properties, and there is no anything similar in Predicate Nominalism.

Problems with Resemblance Nominalism

Accidental coextension objection

Consider the property of “having a heart”. Each living organism that has a heart also has kidneys (I’m not an anatomist though, please forgive me if I’m mistaken. Anyways, for the sake of the argument, let’s assume this is the case). Thus, two properties — “having a heart” and “having kidneys” — always go together. It means that corresponding sets contain the same elements. But, by definition of “set”, it means that they are identical, that is, there is only a single set. Nevertheless, it seems that those two are distinct properties. At least, I find it possible that it can happen that someone will have one property, but not the other. This problem is known as the problem of accidental coextension, and I already outlined it briefly in the context of properties’ individuation.

Hochberg-Armstrong objection

The worry is that in Resemblance Nominalism, one fact can be a truthmaker for more than one proposition. For example,

1) p1 and p2 are absolutely similar particulars; 2) p1 and p2 are distinct.

In Resemblance Nominalism, the truthmaker for those two propositions is the fact that both belong to the same class. I can denote this fact as {p1, p2}. The problem is that the first item can be false: p1 and p2 can be not absolutely similar, but still resemble each other more than anything else. In this case, the truthmaker remains the same: {p1, p2}. So it seems natural that two relations, distinctness, and resemblance, require their own truthmakers. But it can’t be achieved in Resemblance Nominalism; those two are deeply intertwined with each other.

What is a resemblance relation?

What makes resemblance relation a resemblance relation? If we take a resemblance relation as some kind of property, then we should find the resemblance relations that ground it, since resemblance relations are the basis for properties in Resemblance Nominalism. In other words, a resemblance relation between resemblance relations is required, and this is a vicious regress. But Resemblance Nominalism protected itself from this kind of problem. As I’ve mentioned above, resemblance relations are not full-fledged, distinct metaphysical entities which should be analyzed. As Resemblance Nominalists say, those relations are not reified, that is, there are simply no such entities which can resemble. This reduces an explanatory power but saves from uncomfortable regress.

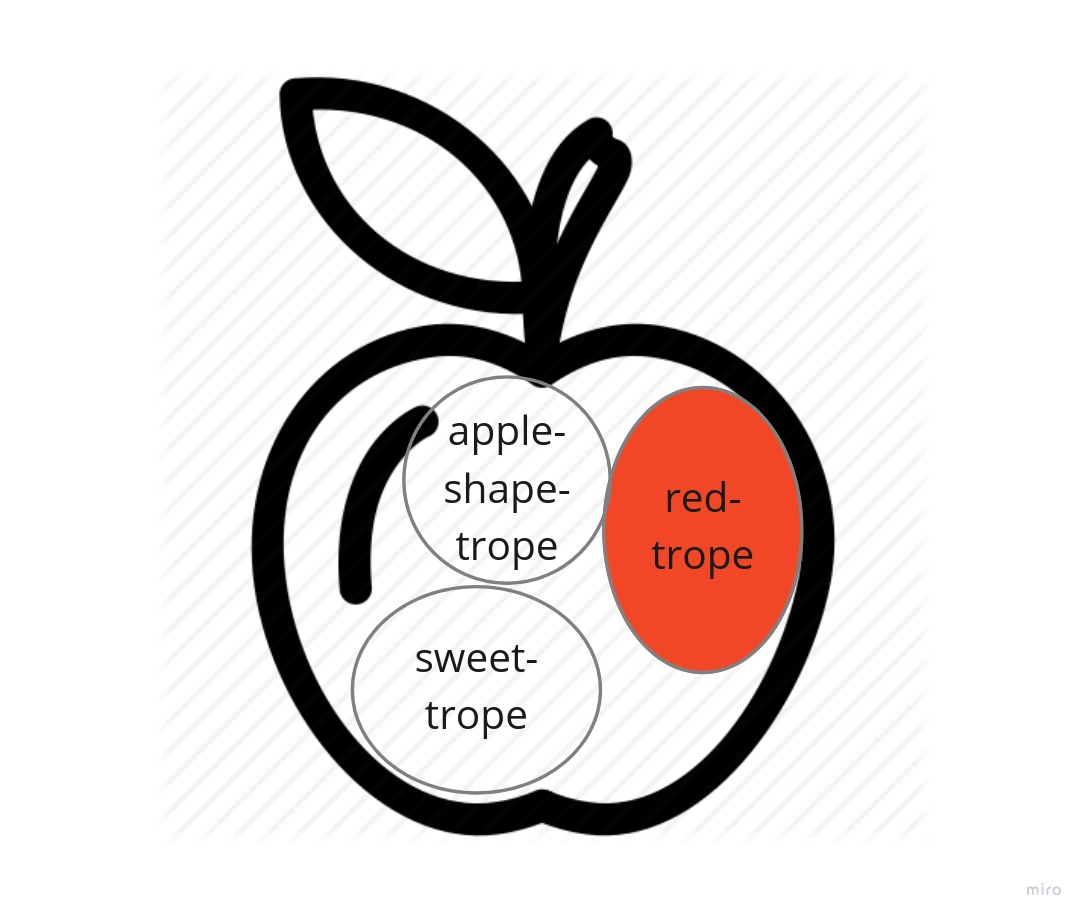

Trope Nominalism

This version of Nominalism is very different from anything else. As a short recap, properties in Realism are Universals, whether transcendent or immanent. In Resemblance Nominalism, a property is a derivative concept represented as a set (the primary one is a resemblance relation). In Trope Nominalism and Trope Theory in general, properties are physical objects called tropes. They are objects in a sense no different than an apple or a table are objects. What makes those objects special and generally not-so-easy to conceive of is the fact that their character is single-dimensional. Take an apple, for example. It’s sweet, red, and crispy. If I’m a Realist, I say that it is such in virtue of instantiating (in Platonism view) or sharing (in Immanent Realism view) the following Universals: SWEET-ness, RED-ness, and CRISPY-ness. If I’m Trope Theorist, I say that an apple has its properties because it consists of a sweet-trope, a red-trope, and a crispy-trope.

Those tropes do not possess character; they are characters, and each of those characters is single-dimensional. Thus, each trope is effectively reduced to a single property its character is grounded in: red-trope is a red property, sweet-trope is a sweet property, and crisp-trope is a crisp property.

Advantages over Resemblance Nominalism

Now, let’s see where Trope Theory (not only its Nominalistic version) beats Resemblance Nominalism. First, it solves a companionship problem. It’s as simple as having two distinct tropes: having-a-heart-trope and having-a-kidney-trope. But conjuring up an image of what actually a trope is, not so much.

Hochberg-Armstrong objection doesn’t apply to Trope Theory. Objects resemblance is “grounded” in a specific set of tropes. If those objects resemble a bit differently, there is a trope that accounts for that difference. That is, for each way two objects can resemble, there is a unique set of tropes that “grounds” that resemblance. To wrap it up, objects resemblance is grounded in tropes sets; objects distinctness is grounded in the set of those objects, which, in turn, is grounded in a fact they are actually distinct.

As a general advantage, not only over Resemblance Nominalism, is a nice fact that tropes are objects. That means that they can do two things. First, they can serve as relata of a causal relation, which can give a deeper account of the nature of causation. Second, they can act as truthmakers.

Problems with Trope Nominalism

What grounds tropes resemblance?

As the song goes, it’s not always rainbows and butterflies. The major problem is giving an account of tropes’ resemblance.

The red of my apple is quantitatively distinct from the red of a firetruck, but qualitatively they are similar. We can think of a normal, customary object as a bundle of tropes. Thus, in Resemblance Nominalist’s view, two objects resemble because both have qualitatively identical tropes. But what makes two tropes similar? That’s where things get ugly.

In the first account, tropes’ resemblance is not grounded in resemblance relation. It’s a brute fact. And this view poses a problem for Trope Theory. It rejects Universals, claiming that they are strange, but comes up with tropes which can’t give an account to generality.

The second account goes somewhat in the spirits of Resemblance Nominalism. It states that two tropes are similar in virtue of resemblance tropes. But, as stated earlier, this results in an unpalatable regress.

A common response to any vicious regress is to postulate something as a brute fact, the one that doesn’t require further explanation. Here, you can do the same thing. You can claim that resemblance tropes are not needed, and that resembling tropes simply resemble. This move, as usual, sacrifices an explanatory power but saves from regress.

Just in case, let me make it clear: Trope Theory is not confined exclusively in Nominalism. It’s orthogonal to Realism-Nominalism distinction. That means that not only Nominalists but Realists as well can be Trope Theorists. And by the way, can you guess what grounds trope resemblance in Realism view? Yep, it’s a Universal. Thus, Universals act as both characterizers and unifiers: that is, they both characterize objects and ground their resemblance. Tropes ground an object’s character, but they are in a weaker position when we look for ways to explain resemblance. If we take a Resemblance Nominalism stance though, we can claim that unifiers are resemblance classes.

Color-thickening dilemma

If tropes are single-charactered, so does a red-trope. But any colored object has a shape. So a colour-trope becomes at least two-dimensional: it has both a colour and a shape.

What are tropes, anyway?

Last but not least — personally, I’m struggling to comprehend what tropes are. I just can hardly imagine them. Of course, I have some image in my head, but let’s be honest: can you show exactly what is an apple-shape-trope and how it’s different from an apple itself?

Despite those cons, tropes are the big thing these days, and we’ll dive a bit deeper into it in the next post on objects.

Conceptualism

Conceptualism is a view which admits the existence of properties, but they exist neither as mind-independent entities such as Universals, nor Resemblance classes, nor tropes. Instead, they are mind-dependent entities, or concepts, like ideas in our heads. As usual, a litmus-test-kind of a question to understand someone’s views goes along the lines of “Why is this apple red? What makes those apples similar?”. In case of Conceptualism, an entity grounding both similarity and property is an idea of redness.

Objections to Conceptualism

First, minds of all humans are different. A little child can misapply the concept of redness, confusing it with something else. Besides, a colour-blind man’s concept of redness is different from a concept of redness of a person without colour blindness. This whole thing would work out if the human mind was some sort of shared entity, like Universals in Realism. But it’s more akin to some kind of wannabe-resembling-tropes, but whose resemblance is not guaranteed. So it seems that the human mind fails both to ground a property and ground objects’ resemblance.

This point can be challenged by claiming that only those human minds count which apply a concept correctly. But I can ask: what makes a concept correct? Treating this as a brute fact smells ostrich. If correct concepts should share a property, it turns a Conceptualist to Realist. If correct concepts should resemble somehow, we land in Resemblance Nominalism bay.

Second, it seems that there are some objective truths. For example, Mount Everest is the highest mountain above sea level. Dogs don’t like cats. Cherry blossoms in spring. All of them would hold even if mankind didn’t exist, and this seems natural. Conceptualists though claim otherwise.

The third objection is that Conceptualists probably confuse two things: properties and ideas about them. When I say that my apple is red, I’m talking about an apple’s property, not about my idea of that property. So it seems that Conceptualism isn’t even supposed to ground properties: it’s about something else entirely.

Concluding a pessimistic postscript

It seems that the problem of what a property actually is and what grounds the similarity of distinct objects can’t be solved. There are effectively two major but equally non-satisfying courses of action here: either postulate some magic entity which does all the dirty job (Universals) or put anything you can’t explain as a brute fact. Probably I should have written this at the beginning of this post, but in that case, I’d deprive you of the pleasure of reading it. Sorry if you didn’t like it.

Further Reading

Probably, properties is one of the most hardcore metaphysical topics. If you’ve made it this far, congratulations. As usual, I’ve outlined only the most prominent and fundamental things here, and there are oh so many topics you can start discovering.

First, no wonder that both utm and sep have great entries about properties.

All prominent types of properties distinction have a special entry at sep. Please enjoy: essential-accidental, intrinsic-extrinsic, determinate-determinables.

For more about semantic theories and intensional logic, you need look no further than sep.

Talking about specifics, one of the most comprehensible posts about Universals is on utm. Sep has a great entry on Realism, and especially I’d love to mention an entry on Platonism. It covers not only Platonism actually, but other views as well, and it’s not only about properties but about other metaphysical items either, such as propositions and numbers. It has a great description of Immanent Realism, as well as other views, and the language is really comprehensible. All in all, it’s a fantastic read, really enjoyed it. One of my all-time favorites. Besides, sep has a nice historical review of the Problem of Universal.

Now to problems in Realism. Sep has deep-dive entries on Bradley’s regress and Russel’s paradox. And if you’re interested in the nature of metaphysical relation, sep has what you need.

Sep again has a great overview of contemporary Nominalism. For more about tropes, please welcome. I’ve talked about abstract objects briefly, you can find some more about them here.

Although Conceptualism has fallen out of fashion lately, the fact that Kant endorsed it makes it notable and worth a read.

And of course, I can’t recommend highly enough a brilliant book, The Fundamentals of Metaphysics which served me as a great introduction to this wonderful branch of philosophy.